Internal Scholarship

Filter

Post List

Do Indigent and Incarcerated Women Have a Real Right to Reproductive Justice?

By Hira Baig Associate Editor, Volume 23 Reproductive justice is not just concerned with women having access to the healthcare they need, it is also concerned with the disparate impact caused by restrictions on reproductive healthcare. Historically, the more restrictions the Court allows on abortion, the more challenging it becomes for indigent women, women of color, and incarcerated women to get the healthcare they need. In order to achieve reproductive justice, scholars and advocates alike ought to think of a comprehensive way to help all women access the reproductive healthcare they need before, during, and even after pregnancy. Currently, the doctrine surrounding reproductive healthcare, primarily abortion, does not account for women’s social contexts and allows restrictions that keep minority and indigent women from enjoying equal protection of the laws. It comes as no surprise that indigent women face severe restrictions when trying to access abortion. Incarcerated women, however, face even greater hurdles. Today, prisons and jails in the United States confine approximately 206,000 women.[1] Approximately 6-10% of women are already pregnant when they enter a prison or jail.[2] Doctor visits for pregnant women in prison are infrequent, with only 54% of women who reported being pregnant in state prisons receiving pregnancy care.[3]

The End of Mass Incarceration: A Blueprint for Transformative Change

By Rasheed Stewart Associate Editor, Vol. 23 He sued the Philadelphia Police Department over 75 times.[1] As a career civil rights and criminal defense attorney he routinely represented individuals subjected to the oppressive forces of racism pervading law enforcement and the criminal justice system.[2] His nationally acclaimed representation of arrested protestors involved with the “Black Lives Matter” movement solidified his reputation among black and brown people as an authentic, hard-nosed movement lawyer.[3] And now, as Philadelphia’s District Attorney, Larry Krasner has managed to put forth a radical, yet replicable platform for ending mass incarceration. Within three months, Krasner has issued several of the most transformative policies that any prosecutor in U.S. history has dared to even imagine. Rather unsurprisingly, Krasner’s new policies have quickly managed to enrage union leaders of the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police,[4] while simultaneously galvanizing influential civil rights activists like Shaun King, in supporting his vision for systemic change.[5] To demonstrate his unrelenting approach to transformative change, Krasner has hit the ground running with a flurry of noteworthy edicts. First, to “broadly reorganize the office’s structure and implement cultural change,” Krasner dismissed 31 members of the office just three days into office, including trial attorneys and several supervisor level staff members.[6] Second, in responding to a judge’s order, Krasner publicly released a secret list of current and former police officers whom prosecutors have sought to keep off the witness stand after a review determined they had a long history of lying, racial bias, or brutality.[7] Moreover, Krasner’s ‘Do Not Call’ list now legitimately sends the foreboding message that cronyism between police officers and ADA’s have no place in an ethically transformed criminal justice system.

The Color of Blight: Michigan’s Troubled History of Urban Renewal Complicates Detroit’s Comeback

By David Bergh Associate Editor, Volume 23 Online Publications Editor, Volume 24 The governmental power of eminent domain has deep roots in the Anglo-American legal tradition. Early English law held that the power to expropriate land was inherent in the Crown’s sovereign authority.[1] As an element of the Crown’s sovereignty, this power was essentially limitless - the King or Queen could take land without compensation, as William I did following the Norman Conquest.[2] The requirement that compensation be paid developed as the absolute power of the Crown waned.[3] This legal doctrine was little altered in the early years of the United States. The Michigan Constitution of 1835 contains no affirmative grant of the power to use eminent domain, only the requirement that property could not be taken “without just compensation therefor.”[4] The fact that the power of eminent domain inhered in the residual sovereignty of the states was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1878.[5]

Can They Do That? (Part 3): Reversing Modern-Day Redlining

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 Production Editor, Volume 24 Patrick Miles Jr. - Michigan candidate for Attorney General Detroit remains the most segregated metropolitan areas in the United States.[1] This is in part thanks to historical practices such as “redlining” where majority African-American neighborhoods were deemed “too risky” for mortgage lending.[2] Though overt discrimination in housing has been outlawed[3], the systems created for that purpose often remain, in whole or in part. One Democratic candidate for Michigan Attorney General, Pat Miles, has pledged to use the office to combat modern-day redlining.[4] Patrick Miles Jr., who prefers to go by Pat, is the former U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Michigan, serving from 2012 to 2017. Prior to that appointment, his experience was largely in private sector and telecommunications law. As part of our ongoing series examining the campaign pledges of candidates for that office, we have to ask: can he do that? The study Mr. Miles cited in his pledge to defend consumers was conducted by Reveal, a project of the Center for Investigative Journalism. Its analysis of data from 61 metro areas across 2015 and 2016 resulted in a blunt conclusion: “Fifty years after the federal Fair Housing Act banned racial discrimination in lending, African Americans and Latinos continue to be routinely denied conventional mortgage loans at a rate far higher than their white counterparts.”[5] In Detroit, that trend meant an African-American applicant was almost twice as likely to be denied a conventional home mortgage.[6] Defenders of current mortgage practices point to what they believe are flaws in that data. They argue that high rejection rates are a result of large lenders and technology, making applying for a mortgage easier and leading to more applicants with subpar credit.[7] Yet this explanation ignores that federal housing policy codified racial minority populations as a lending risk for years, and those policies’ effects persist today.[8] Without the access to long-term investment and wealth from generations ago, today’s minority borrowers are still subject to these trends.[9]

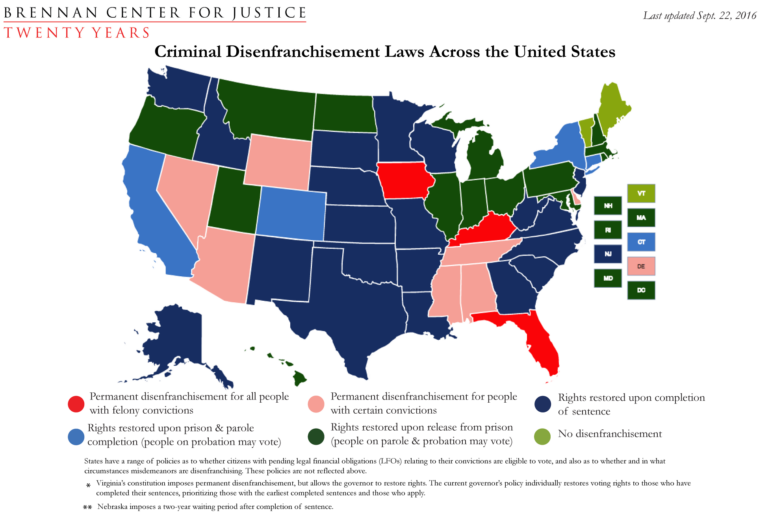

Forever Barred: Examining Felony Disenfranchisement in Florida

By Shanene Frederick Associate Editor, Volume 23 Executive Articles Editor, Volume 24 Desmond Meade was convicted on felony drug and firearm charges back in 2001.[1] Meade, who previously battled drug addiction and experienced homelessness, went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University College of Law.[2] However, his decades-old convictions continue to affect his life today in the form of disenfranchisement. In 2016, Meade could not vote for his wife during her bid for office in the Florida House of Representatives because Florida permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting after they complete their sentences.[3] As the director of Floridians for Fair Democracy, Meade and his team of volunteers have petitioned for over two years in an effort to get a constitutional amendment proposal on Florida’s November 2018 state ballot. [4] Last month, Floridians for Fair Democracy announced that the campaign, Florida Second Chances, had surpassed 799,000 certified signatures, putting it above the required threshold to get on the ballot.[5] If passed, the amendment would restore voting rights to over 1.5 million Floridians, who have been subject to what are arguably the harshest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. [6] The states take various approaches to felony disenfranchisement. As of 2016, all states but Maine and Vermont bar those incarcerated from voting, thirty states restrict those on felony probation from voting, and thirty-four states restrict parolees from voting.[7] Florida is one of twelve states that strip away voting rights post-sentence and post-parole.[8] The effects of Florida’s disenfranchisement scheme are particularly startling: Florida holds 27 percent of the nation’s disenfranchised population, and the total 1.5 million post-sentence disenfranchised individuals make up 48 percent of those who are disenfranchised post-sentence nationally.[9] In 2016, 10.4 percent of Florida’s eligible voting age population was denied the right to vote.[10]

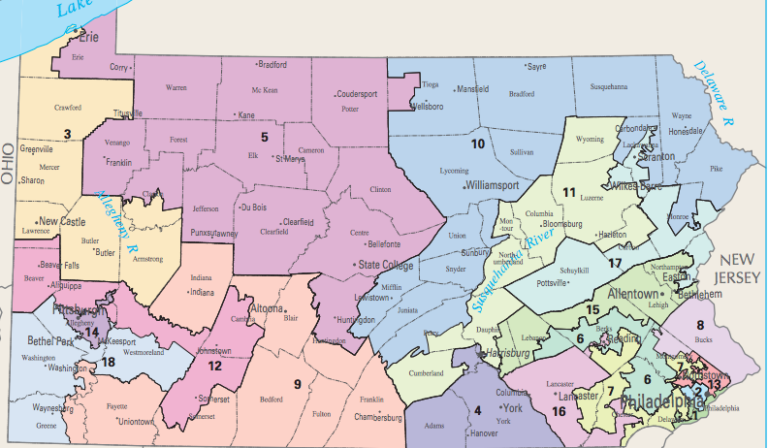

Gerrymandering: Beyond the Partisan Divide

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 Pennsylvania's old Congressional map. Pennsylvania has a long history of a fierce partisan political divisions, due in part to its extremely diverse electorate, geography, and economy.[1] This divide results in massive campaign spending each election cycle and has earned Pennsylvania the label of a battleground or purple state every four years.[2] With this background in mind, it should be no surprise that Pennsylvania is a hub for the practice of gerrymandering which often has a disproportionate effect on communities of color. For partisan gerrymandering, “[t]he playbook is simple: Concentrate as many of your opponents’ votes into a handful of districts as you can, a tactic known as ‘packing.’ Then spread the remainder of those votes thinly across a whole lot of districts, known as ‘cracking.’”[3] Fortunately, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has stepped in, dubbing the Republican created map used over the last six years unconstitutional.[4] In turn, the Court redrew a far more equitable map that may provide a model for nonpartisan redistricting in years to come.[5] The new Congressional map drawn by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in the wake of its recent decision. The new map moves away from the fracturing of communities into disparate districts like the Republican map and attempts to keep counties and municipal areas intact when establishing congressional districts.[6] While the Republican drawn map split 28 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties into separate congressional districts, the new map will only divide 13.[7] An analysis conducted by the Washington Post finds that the new map erases many of the zig-zag lines that were commonplace under the Republican plan, especially in and around urban areas, and eliminates over 1,100 of electoral boarders, a reduction of approximately 37 percent.[8] This focus on compact districts and keeping communities intact when drawing congressional lines is especially notable in Philadelphia, where the new map splits the city into fewer districts.[9] Each of these changes moves towards congressional districts looking “geographically normal,” a goal shared by many nonpartisan experts in the field.[10] Under the new map, districts are defined by strong community ties, unlike the old map where a seafood restaurant held the seventh congressional district “together like a piece of Scotch tape.”[11]

Latina Lawyers: Underrepresented and Overqualified

By Cleo Hernandez Associate Editor, Volume 23 Editor-in-Chief, Volume 24 In 2009, Justice Sotomayor became the first ever Latina to serve on the United States Supreme Court. Gender violence, sexual harassment, and feminism have all been dancing around on the center stage of world politics lately, as displayed by the traction that the #MeToo movement has gained on both social and mainstream media platforms. And indeed, immense bravery is required of every woman and man that speaks out as a victim of sexual harassment or domestic violence. However, packaging these complex issues into a hashtag, or a sound bite, or a news article has inevitably erased the nuances that define modern day feminism, and that affects women of color. In addition, the current national controversy about immigration has become overtly racialized and criminalized putting certain racial and ethnic groups in the spotlight. These national moods compound to make today a particularly tough time to be a Latina in America. Especially if one is a Latina in a profession with few peers of a similar racial and gender identity. Latinas comprise less than two percent of attorneys in the United States.[1] Even without the recent publicity surrounding these new political conversations, a Latina lawyer faces a career path filled with race, class, and gender-based obstacles.[2] A lack of role models and financial resources can be a barrier for Latinas to even begin to consider attending law school.[3] Once in law school and as an attorney, the lack of Latinas in the profession can feel isolating, and can create low self-esteem in Latinas.[4] There is hardship involved when assimilating and fitting into the law school culture, being tokenized, and being afraid to be labeled as either too passive, or as a “fiery” or “hot-headed” Latina.[5] Furthermore, microaggressions and overt racism can make it difficult to navigate courtrooms and law firms.[6] Latina lawyers report oftentimes being misidentified in the courtroom as the bailiff, the interpreter, the secretary, or the defendant.[7] Additionally, when a Latina lawyer is promoted, she will perceive (or hear directly from others) that her coworkers see her as not qualified for the new position, and believe that she only received the promotion because she was a minority or a woman.[8]

Attacks on Asian Americans

By Ben Cornelius Associate Editor, Volume 23 Kyle Descher was born in Korea, but adopted at a young age by an American couple. [1] Back when he was a college student he and a roommate headed out to a bar after a Washington State University football victory over Oregon. [2] As the pair approached the bar, the remark “fucking Asian” was hurled at Descher. Descher ignored the remark and went about his night.[3] But a few moments later an unknown assailant unleashed a vicious blow that broke Descher’s jaw in two places, and knocked him to the floor, unconscious and bleeding badly.[4] It took three titanium plates to get his jaw back together.[5] His mouth was wired shut.[6] He had to eat through a straw and would wake up several times a night from the throbbing pain.[7] Hate crimes and crimes, and crimes in general, against Asian-Americans have been steadily rising. [8] In Los Angles, an L.A. County Commission on Human Relations report found that crimes targeting Asian-Americans tripled in that county between 2014 and 2015.[9] These sort of attacks also rose in New York City.[10] Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of Asian and Pacific Islander victims of robbery rose from 11.6 percent to 14.2 percent; felonious assault from 5.2 percent to 6.6 percent; and grand larceny from 10.3 percent to 13.5 percent.[11] The robbery statistic is particularly interesting, as robberies overall were down 29 percent over that same period despite the increase in robberies of Asians.[12] Due to likely underreporting, the statistics may be much more troubling. Language barriers, immigration status, and unfamiliarity with the criminal justice system can cause Asians to be hesitant to report crimes.[13] “They look at us as easier targets,” said Karlin Chan, an activist in New York’s Chinatown.[14] Unfortunately, vicious race-based assaults on Asian-Americans are nothing new.[15] Cases of hate crimes against Asian-Americans can be found all the way back to the 1800’s.[16] The white supremacist group ‘Arsonists of the Order of Caucasians’ savagely murdered four Chinese men whom they blamed for taking away jobs from white workers.[17] The victims were tied up, had kerosene poured on them and then were set ablaze.[18] In 1987, a New Jersey gang calling itself the "Dotbusters" vowed to drive East Indians out of Jersey City by vandalizing Indian-owned businesses.[19] The gang also got violent and used bricks to bludgeon a young South Asian male into a coma.[20] Regardless of how many generations a person may have been here, Asians are often seen as the perpetual foreigner hell-bent on stealing jobs and taking over the country.[21]Introducing the MJR&L Volume 24 Executive Editorial Board

Congratulations to our Volume 24 Executive Editorial Board! Editor-In-Chief Cleo Hernandez Managing Editor Gabriela Hybel Managing Executive Editor Morgan Birck Production Editor John Spangler…

Undoing Past Wrongs: Chipping Away at Capital Punishment

By Hira Baig Associate Editor, Volume 23 The vast majority of countries, 140 to be exact, consider the death penalty cruel and unusual punishment.[1] The current constitution of Germany, for example, forbids use of capital punishment.[2] Lawyer and activist Bryan Stevenson comments on this policy choice by suggesting there is a connection between Germany’s consciousness of its history and its refusal to use the death penalty.[3] It would be harrowing, after all, for the German government to have a criminal punishment that facilitates the state-sanctioned killing of people after the Holocaust. America, on the other hand, turns a blind eye to its history. Celebrating civil rights leaders and electing a black president does not rid this country of its past sins—especially if those sins are manifesting today in different form. The grave inequality between the races was embedded into our Constitution and our laws. While the Constitution created a form of government for “the people,” it was used for over a century to uphold slavery. Once formal slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, the Constitution was used to justify discriminatory treatment, Jim Crow, and today, it is used to embolden our system of mass incarceration. The Constitution also upholds use of the death penalty.[4] The killing of mostly black men is not a violation of the Eighth Amendment, which ought to protect people from cruel and unusual punishment.[5] And in southern states, black defendants are 22 times more likely to get the death penalty if the alleged victim is white.[6] In my home-state of Texas, juries can still sentence mentally ill offenders to death. Texas has one of the busiest death rows in the country, and recently, a lawmaker filed a bill that might curtail use of this punishment.[7] This bill limits the maximum punishment for mentally ill people to life in prison without parole. Mitigating use of the death penalty ought to be considered a valiant effort. After all, Texas uses the death penalty more than any other state.[8]