All content tagged with: Systemic Oppression

Filter

Post List

Carceral Socialization as Voter Suppression

In an era of mass incarceration, many people are socialized through interactions with the carceral state. These interactions are powerful learning experiences, and by design, they are contrary to democratic citizenship. Citizenship is about belonging to a community of equals, being entitled to mutual respect and concern. Criminal punishment deliberately harms, subordinates, and stigmatizes. Encounters with the carceral system are powerful experiences of anti-democratic socialization, and they impact peoples’ sense of citizenship and trust in government. Accordingly, a large body of social science research shows that eligible voters who have carceral contact are significantly less likely to vote or to participate in politics. Hence, the carceral system’s impact on political participation goes well beyond those who are formally disenfranchised due to convictions. It also suppresses participation among the millions of legally eligible voters who have not been formally disenfranchised—people who have had more fleeting encounters with law enforcement or vicarious interactions with the carceral system. This Article considers the implications of these findings from the perspective of voting rights law and the constitutional values underlying it. In a moment when voting rights are under siege, voting rights advocates are in a heated discussion about how our federal and state constitutions protect ideals of democratic citizenship and political equality. This discussion has largely (and for good reason) focused on how the law should address what I call “de jure” suppression: tangible election laws and policies that impose legal barriers to voting, or dilute voting power. Eliminating these formal barriers to voting is vital. But, I argue, fully realizing the constitutional values underlying voting rights will also require also addressing what I call “de facto” suppression, or suppression through socialization. This occurs not through formal legal restrictions on voting, but when state institutions like the carceral system systematically socialize citizens in a manner that is incompatible with democratic citizenship. I show how de facto suppression threatens the constitutional interests protected by the right to vote just like de jure suppression does. In short, by systematically socializing people in a manner that is fundamentally incompatible with democratic citizenship, the state can effectively strip a citizen of much of the instrumental and intrinsic value conferred by the right to vote. Those who are concerned about advancing and protecting voting rights should understand the carceral system’s anti-democratic socialization as a form of political suppression—one that should warrant constitutional scrutiny for the same reasons that de jure suppression should warrant scrutiny.Racism Pays: How Racial Exploitation Gets Innovation Off the Ground

Recent work on the history of capitalism documents the key role that racial exploitation played in the launch of the global cotton economy and the construction of the transcontinental railroad. But racial exploitation is not a thing of the past. Drawing on three case studies, this Paper argues that some of our most celebrated innovations in the digital economy have gotten off the ground by racially exploiting workers of color, paying them less than the marginal revenue product of their labor for their essential contributions. Innovators like Apple and Uber have been able to racially exploit workers of color because they have monopsony power to do so. Workers of color have far fewer outside options than white workers, owing to intentional and structural discrimination against workers on the basis of their race. In the emerging digital economy, racial exploitation has paid off by giving innovators a workforce that is cheap, easy to scale, flexible, and productive—the kind of workforce that is especially useful in digital markets, where a first-mover advantage often translates to winner-take-all. This Paper argues that these workers should be paid the marginal revenue product of their labor, and it proposes a number of potential ways to do so: by increasing worker compensation or worker power. More generally, I argue that we should value the essential contributions of workers of color and immigrant workers who make innovation possible.Bankruptcy in Black and White: The Effect of Race and Bankruptcy Code Exemptions on Wealth

Bankruptcy law in the United States is race-neutral on its face but, in practice, race matters in bankruptcy outcomes. Our original research provides an empirical look at how the facially neutral laws that allow debtors to retain assets in bankruptcy cases result in disparate outcomes for Black and white debtors. Racial differences in asset retention in bankruptcy cases play a role in perpetuating wealth inequality between Black and white debtors. Existing bankruptcy data lacks individual-level characteristics such as race, which inhibits researchers’ ability to adequately assess biases or unintended consequences of laws and policies on subsets of the population. Thus, we construct a novel data set using bankruptcy data from Washington D.C. in 2011 and imputing race. The data demonstrates that facially race-neutral bankruptcy laws contribute to racially disparate outcomes by allowing white debtors to keep larger amounts of both personal and real property. First, exemption laws allow every bankruptcy filer to retain some personal property even if they do not repay their creditors in full. At the median, white filers in the District of Columbia claimed $10,150 in exemptions, relative to $8,359 for Black filers. In other words, the median white filer kept roughly $1,800 more of their property than Black filers, despite reporting similar overall personal property values. Second, exemption laws allow every bankruptcy filer to retain some (or all) equity in their home. Unlike personal property, where Black and white debtors enter bankruptcy with about the same amount of property, white debtors enter bankruptcy with more home equity than Black debtors ($585,000 compared with $251,600 at the median). Unsurprisingly, then, white debtors also leave bankruptcy with more home equity (e.g., the median Black filer retains roughly 80% less in home equity than white filers). Although bankruptcy laws do not inflate the value of white filers’ personal or real property values relative to Black debtors, our exemption rules contribute to white debtors leaving bankruptcy with greater wealth than Black debtors. By protecting certain assets like home equity, which are unevenly distributed in our sample across Black and white debtors, bankruptcy law appears to play a role in perpetuating wealth inequality. Even where assets are more evenly distributed, as personal property was in our sample, bankruptcy law leaves Black debtors with a less robust “fresh start” than white debtors.Carceral Intent

For decades, scholars across disciplines have examined the stark injustice of American carceralism. Among that body of work are analyses of the various intent requirements embedded in the constitutional doctrine that governs the state’s power to incarcerate. These intent requirements include the “deliberate indifference” standard of the Eighth Amendment, which regulates prison conditions, and the “punitive intent” standard of due process jurisprudence, which regulates the scope of confinement. This Article coins the term “carceral intent” to refer collectively to those legal intent requirements and examines critically the role of carceral intent in shaping and maintaining the deep-rooted structural racism and sweeping harms of America’s system of confinement. This Article begins by tracing the origins of American carceralism, focusing on the modern prison’s relationship to white supremacy and the post-Emancipation period in U.S. history. The Article then turns to the constitutional doctrine of incarceration, synthesizing and categorizing the law of carceral intent. Then, drawing upon critical race scholarship that examines anti-discrimination doctrine and the concept of “white innocence,” the Article compares the law’s reliance on carceral intent with the law’s reliance on discriminatory intent in equal protection jurisprudence. Critical race theorists have long critiqued the intent-focused antidiscrimination doctrine as incapable of remedying structural racism and inequities. The same can be said of the doctrine of incarceration. The law’s preoccupation with an alleged wrongdoer’s “bad intent” in challenges to the scope and conditions of incarceration makes it ill-suited to remedying the U.S. prison system’s profoundly unjust and harmful features. A curative approach, this Article asserts, is one in which the law focuses on carceral effect rather than carceral intent, as others have argued in the context of equal protection. While such an approach will not remedy the full scope of harms of U.S. incarceration, it would be a start.Racist at its Core: The Continual Push for Work Requirements in Public Assistance Programs

By: Liza DavisExecutive Editor, Vol. 27 In March of 2014, now-retired congressional leader Paul Ryan appeared on a radio talk show to discuss the causes of “the economic conditions…plagu[ing] much of the country.”[1] At one point, Ryan said, “We’ve got this tailspin of culture, in our inner cities in…

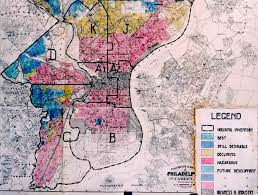

Exploring Mapping Inequality: Redlining Close to Home

By: Eve HastingsAssociate Editor, Vol. 26 Background Mapping Inequality is a website created through the collaboration of three teams at four universities including the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, University of Maryland, and Johns Hopkins University.[1] I was introduced to the website through my Property professor during the…

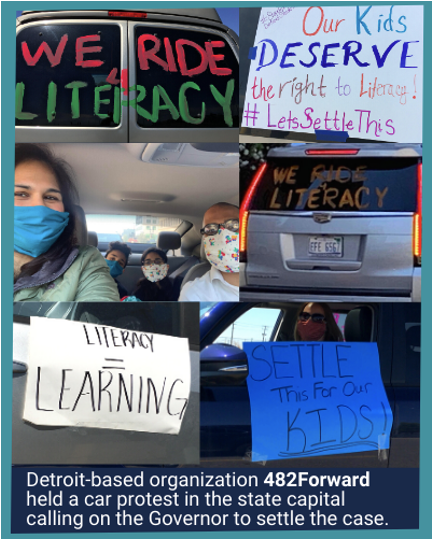

The Right to Education: Where We Go Next

By: Daniel BaumAssociate Editor, Vol. 26 This blog calls on scholars and practitioners to advocate, and for courts to hold, that every student in this country—no matter whether they live in Orange, Wayne, or Washtenaw County, or whether their skin is Black, white, or neither—possesses a fundamental right to…#ForTheCulture: Generation Z and the Future of Legal Education

Generation Z, with a birth year between 1995 and 2010, is the most diverse generational cohort in U.S. history and is the largest segment of our population. Gen Zers hold progressive views on social issues and expect diversity and minority representation where they live, work, and learn. American law schools, however, are not known for their diversity, or for being inclusive environments representative of the world around us. This culture of exclusion has led to an unequal legal profession and academy, where less than 10 percent of the population is non-white. As Gen Zers bring their demands for inclusion, and for a legal education that will prepare them to tackle social justice issues head on, they will encounter an entirely different culture—one that is completely at odds with their expectations. This paper adds depth and perspective to the existing literature on Generation Z in legal education by focusing on their social needs and expectations, recognizing them as critical drivers of legal education and reform. To provide Gen Z students with a legal education that will enable them to make a difference for others—a need deeply connected to their motivators and beliefs—law school culture must shift. Reimagining, reconstituting, and reconfiguring legal education to create a culture of inclusion and activism will be essential and necessary. Engaging in this work “for the culture” means getting serious about diversifying our profession by abandoning exclusionary hiring metrics, embedding social justice throughout the law school curriculum, and adopting institutional accountability measures to ensure that these goals are met. Gen Zers are accustomed to opposing institutions that are rooted in inequality; law schools can neither afford, nor ignore the opposition any longer. We must begin reimagining legal education now—and do it, for the culture.The Soul Savers: A 21st Century Homage to Derrick Bell’s Space Traders or Should Black People Leave America?

Note: Narrative storytelling is a staple of legal jurisprudence. The Case of the Speluncean Explorers by Lon Fuller and The Space Traders by Derrick Bell are two of the most well-known and celebrated legal stories. The Soul Savers parable that follows pays tribute to Professor Bell’s prescient, apocalyptic racial tale. Professor Bell, a founding member of Critical Race Theory, wrote The Space Traders to instigate discussions about America’s deeply rooted entanglements with race and racism. The Soul Savers is offered as an attempt to follow in Professor Bell’s narrative footsteps by raising and pondering new and old frameworks about the rule of law and racial progress. The year 2020 marks the thirty-year anniversary of Bell’s initial iteration of the Space Traders tale.Law and Anti-Blackness

This Article addresses a thin slice of the American stain. Its value derives from the conversation it attempts to foster related to reckoning, reconciliation, and redemption. As the 1930s Federal Writers’ Project attempted to illuminate and make sense of slavery through its Born in Slavery: Slave Narratives From 1936-1938, so too this project seeks to uncover and name law’s role in fomenting racial division and caste. Part I turns to pathos and hate, creating race and otherness through legislating reproduction— literal and figurative. Part II turns to the Thirteenth Amendment. It argues that the preservation of slavery endured through its transformation. That the amendment makes no room for equality further establishes the racial caste system. Part III then examines the making of racial division and caste through state legislation and local ordinances, exposing the sophistry of separate but equal. Part IV turns to the effects of these laws and how they shaped cultural norms. As demonstrated in Parts I-IV, the racial divide and caste system traumatizes its victims, while also undermining the promise of constitutional equality, civil liberties, and civil rights.