All content tagged with: Politics

Filter

Post List

Showing the Government CARES – Using Prior Crises to Support Minority Communities

By Lexi Wung Associate Editor, Vol. 26 llustration from rawpixel.com At the beginning of my second year of law school I tested positive for COVID-19. I spent my first week of classes isolating in remote apartment housing on Michigan’s north campus. Aside from mild symptoms and lingering fatigue, I…

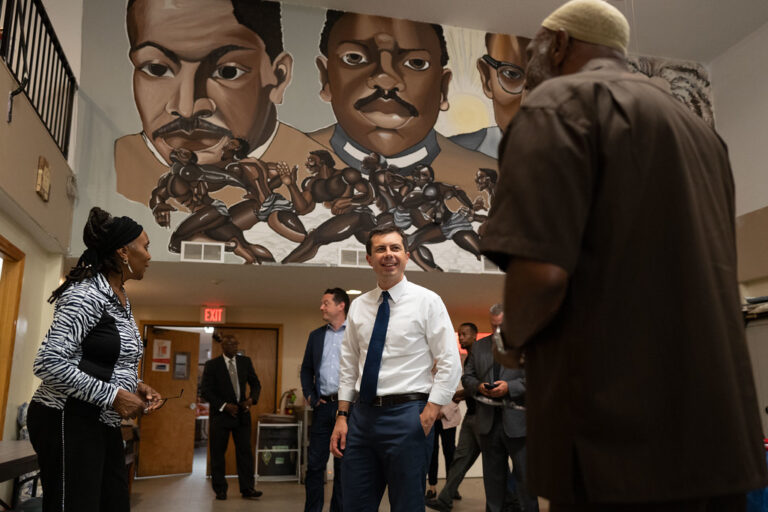

Pete Buttigieg’s Bold Ideas?

By Jonah Rosenbaum Associate Editor, Vol. 25 As Pete Buttigieg surged into being a serious contender for the Democratic nomination, aided in part by a not so subtle push from a fawning media, a less flattering narrative has emerged—the white, small town Mayor of South Bend, Indiana…

Donald Trump: The Champion of Criminal Justice Reform?

By Tamar Alexanian Associate Editor, Vol. 25 On October 25, 2019, the 45th President of our great, fair, and just nation received the Bipartisan Justice Award at the 2019 Second Step Presidential Justice Forum, an event organized by the 20/20 Bipartisan Justice Center.[1] The Justice Center gave…

Litigating the Constitutionality of Trump’s National Emergency Declaration

By Sam Kulhanek Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On February 15, 2019, President Trump declared a national emergency in order to push forward his long-standing plans to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border.[1] Earlier that same day, Trump had signed an act of Congress appropriating $1.375 billion for the border wall, which fell far short of his desired $5.7 billion and also came with certain restrictions.[2] Trump then announced his intention to declare a national emergency pursuant to the National Emergencies Act[3] in order to get the rest of his desired funding for the wall. Trump’s declaration is now under attack on several fronts as lawmakers, states, landowners, and advocates challenge this attempted “end run” around Congress.[4] In his proclamation declaring the emergency, Trump stated that the southern border “presents a border security and humanitarian crisis that threatens core national security interests,” and that it was necessary for additional troops and funding for military construction to be made available.[5] Trump now claims that he will have up to $8.1 billion at his disposal in order to build the border wall and finally fulfill his long-time campaign promise.[6] However, Trump is also facing numerous lawsuits challenging the legality of his actions, which many view as an attempt to access funds that Congress explicitly refused to give him, thereby violating the constitutional separation of powers.[7]

How Jeff Sessions is Quietly Transforming Immigration Law to Promote His Anti-Immigrant Agenda

By Samantha Kulhanek Associate Editor, Vol. 24 The Attorney General’s authority to refer Board of Immigration Appeals (“BIA”) decisions to himself for review was established via regulation in 1940,[1] and yet this power appears to be receiving more attention today than it ever has.[2] The appointment of Jeff Sessions as Attorney General prompted a string of these unique reviews,[3] in which Sessions has attempted to profoundly alter the way immigration courts interpret certain provisions of the Immigration & Nationality Act (“INA”). The most publicized example of Sessions’s exercise of this referral power thus far has been his decision in Matter of A-B-, where he attempted to effectively narrow the circumstances in which individuals fleeing gang violence or domestic abuse may receive asylum in the U.S.[4] However, some of Sessions’s other decisions resulting from his use of the referral power have received relatively little attention, and yet may have massive consequences for the immigration system. Three decisions in particular have attacked the discretion of immigration judges and threaten to interfere with their judicial independence and how they handle their dockets.

Countering Violent Extremism Under the Trump Administration: The True Focus is Minority Communities, Not Domestic Extremism

By Mackenzie Walz Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Through the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Congress established the prevention of domestic terrorist attacks as one of the Department of Homeland Security’s primary missions and appropriated ten million dollars “for a countering violent extremism (CVE) initiative to help states and local communities” combat these threats.[1] Pursuant to the Act, in 2011 the Obama Administration created and implemented the “first national strategy” to prevent domestic violent extremism, entitled “Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States.”[2] Taking a community-based approach, the program was designed to distribute federal funds to local organizations – educational institutions, non-profits, or law enforcement agencies – which would provide community members with the requisite resources and education to identify signs of extremist radicalization.[3] The ultimate goal was for community members and local leaders to develop relationships of trust through this engagement, which would empower community members, once educated, to report any identified signs of extremism.[4] While the program was designed to combat all types of violent extremism, in operation and effect it targeted Muslim-American communities.[5] Instead of building relationships of trust between community members and these local leaders, as it was intended to do, it bred mistrust, as the program in some communities “appeared to be doubling as a means of surveillance.”[6] This mistrust made some members of the Muslim-American community hesitant to reach out to law enforcement officers to report signs of radicalization,[7] rendering the outreach program less effective.

Trump’s Efforts to Deport People Back to “Sh**hole” Countries Stalled by Equal Protection Clause

By Kerry Martin Associate Editor, Vol. 24 How racist can the President of the United States be in determining immigration policy before he violates the Equal Protection Clause? A lot depends on who the target is—and with recipients of temporary protected status, Trump may have picked on the wrong people. Donald Trump announced his candidacy with anti-Latino animus (“When Mexico sends its people…”)[1] and has not backed down since entering the White House. In response to allegations of crime by Central American immigrants on Long Island, President Trump remarked: “They come from Central America. They’re tougher than any people you’ve ever met. They’re killing and raping everybody out there.”[2] Of Haitians, Trump said they “all have AIDS”[3] and asked, “why do we need more Haitians?”[4] And in response to an immigration proposal that would have included protections for Salvadorans, Haitians, and some Africans, Trump inquired, “Why are we having all these people from shithole countries come here?”[5] This racial animus seems inextricable from every immigration policy decision made by the Trump Administration, from ramping up internal enforcement and border protection, to pushing for legislation that would curb “chain migration” and fund a border wall. But it has proven difficult, at least for purposes of stating a legal claim, to tie these broad-sweeping policy choices to Trump’s racist statements, even if “[e]veryone knows”[6] that the two are related.

The Color of Blight: Michigan’s Troubled History of Urban Renewal Complicates Detroit’s Comeback

By David Bergh Associate Editor, Volume 23 Online Publications Editor, Volume 24 The governmental power of eminent domain has deep roots in the Anglo-American legal tradition. Early English law held that the power to expropriate land was inherent in the Crown’s sovereign authority.[1] As an element of the Crown’s sovereignty, this power was essentially limitless - the King or Queen could take land without compensation, as William I did following the Norman Conquest.[2] The requirement that compensation be paid developed as the absolute power of the Crown waned.[3] This legal doctrine was little altered in the early years of the United States. The Michigan Constitution of 1835 contains no affirmative grant of the power to use eminent domain, only the requirement that property could not be taken “without just compensation therefor.”[4] The fact that the power of eminent domain inhered in the residual sovereignty of the states was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1878.[5]Trump’s Travel Ban: Is There a Way Out?

By Rita Samaan Associate Editor, Vol. 22 In the wake of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ decision to block President Trump’s Executive Order 13769 (“Executive Order”), the President vowed to issue “a new executive action . . . that will comprehensively protect our country.”[1] The President’s officials have disclosed their intent to advocate more strongly for why the revised ban should apply to the seven listed countries.[2] They hope to overcome the amassing legal scrutiny of the travel ban and make it less of a “Muslim ban” in effect.[3] So, who stood in the way of Trump’s order? Washington and Minnesota brought an action against President Trump, the Secretary of Homeland Security, Secretary of State, and the United States for a declaratory judgment that portions of the Executive Order were unconstitutional.[4] The states filed a motion for a temporary restraining order (TRO).[5] The United States District Court for the Western District of Washington granted the TRO and denied motion for stay pending appeal.[6] The federal government moved for an emergency stay of the district court’s TRO while waiting for its appeal to proceed.[7] The decision on the government’s motion for an emergency stay came before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The court faced two questions: 1) whether the Government had made a strong showing of its likely success in its appeal and 2) whether the district court’s TRO should be stayed in light of the relative hardship and the public interest.[8] The court answered “no” to both questions,[9] listing several reasons for its decision.Imposition of Identity: Trump’s Immigration Order and the Racialization of Islam

By Asma Husain Associate Editor, Vol. 22 On January 27 of this year, newly-inaugurated President Trump issued an executive order temporarily immigration from Iran, Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Somalia, Libya, and Yemen pending a report from the Department of Homeland Security, to be completed within thirty days of the order’s date.[1] Despite singling out only Muslim-majority countries, and despite Trump’s campaign promise of a “total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,”[2] the Trump administration has refused to characterize the immigration order as a “Muslim ban.” However, the ban impacts predominantly Muslim and Muslim-looking people and contributes to the classification of Muslims as a monolithic race by both the state and popular opinion. The immigration order is couched in language about national security, but there is no doubt of its intentions to single out Muslim immigrants. A member of Trump’s team during the presidential election, Rudy Giuliani, spoke with Fox News about how Trump told him to craft a Muslim ban that could be carried out legally.[3] And what we did was, we focused on, instead of religion, danger – the areas of the world that create danger for us. What is a factual basis, not a religious basis. Perfectly legal, perfectly sensible. And that’s what the ban is based on. It’s not based on religion. It’s based on places where there are substantial evidence that people are sending terrorists into our country.[4]