All content tagged with: Incarceration

Filter

Post List

Improving Michigan’s School Expulsion Policy Would Help Cut School to Prison Pipeline

By Kara Crutcher Associate Editor, Vol. 24 There is a strong correlation between the amount of time that K-12 students spend out of school for disciplinary reasons, and the likelihood of them ending up in the correctional system. This concept, known as the school to prison pipeline, is heavily present in the lives of black and brown students that are subject to harsh disciplinary action more so than their white counterparts.[1] Until 2016, the Michigan education system was known for its zero-tolerance policies.[2] Zero tolerance led at least twelve Michigan school districts to over-suspend students of color.[3] Under these policies, school boards had no discretion over the disciplinary action taken towards a student that brought a dangerous weapon to school, engaged in criminal sexual conduct, committed arson, or physically assaulted a staff member or school volunteer. Rather, if a student engaged in any of these behaviors, they were subject to mandatory expulsion, where no other public school in the district would be required to accept them as a new student.[4] This left many young people of color in an extremely vulnerable position, as there is a greater chance that they will become disengaged in their education, and become involved in activities that can lead to incarceration.[5] In an effort to use a more holistic approach in K-12 discipline, Michigan representatives introduced Public Act No. 360[6] in 2016. The act “creates a rebuttable presumption that a suspension of 10 days or more and/or an expulsion”[7] is unjustified unless seven factors are considered. These factors include a student's age, disciplinary history, learning and/or emotional disabilities, the seriousness of behavior, whether the behavior posed a safety risk, whether restorative practices had been already utilized, and whether a lesser intervention would address the behavior.[8] The act went into effect August 1, 2017.[9]

The First Step Act: It Needs to be the First Step

By Jules Hayer Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On December 21, 2018 the President signed into law the First Step Act. The First Step Act is a criminal justice reform bill that decreases mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenses, modifies the three strikes rule from requiring a life sentence to mandating a 25-year sentence, and gives judges more discretion when sentencing people convicted of nonviolent drug offenses. The Act also makes retroactive a 2010 law that reduced the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses, and also includes provisions that improve prison conditions.[1] These tangible changes demonstrate that parts of the First Step Act are a push in the right direction for criminal justice reform. After all, this year the collective changes outlined in the Act are expected to reduce the sentences of more than 9,000 people currently serving time. Yet critics of the Act point out that this impact is nominal. Not only will this Act impact less than 5% of the federal prison population, which now exceeds 180,000,[2] the Act will also only impact those serving time in federal prisons, when in fact more than 88% of the nation’s prison population is serving time in the state system.[3] And rather than demonstrating laudable progress, some parts of the Act demonstrate just how fundamentally flawed the policies that were previously in place were. For example, the Act prohibits the shackling of women during childbirth and prior to the completion of postpartum recovery, mandates that the Bureau of Prisons make tampons and sanitary napkins available to women in prison for free, and requires that efforts are made to place individuals within 500 driving miles of their primary residence.[4] While all of these changes demonstrate a degree of progress, they also bring to light how damaging many of the Bureau of Prisons policies have been in the past.

California’s Efforts to Reform Bail Leaves Much to be Desired

By Jules Hayer Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Despite recent developments in California to overhaul the bail system, the state still has a long way to go in order to create effective change. In January of this year the California Court of Appeals ruled that, before setting bail, judges must take into account the financial situation of a defendant and determine whether the defendant can be released without imposing a danger to public safety.[1] Moreover, the prosecution bears the burden of presenting clear and convincing evidence which establishes that no conditions of release would ensure the safety of the community, thus requiring the confinement of the person while awaiting trial.[2]From Pelican Bay to Palestine: The Legal Normalization of Force-Feeding Hunger-Strikers

Hunger-strikes present a challenge to state authority and abuse from powerless individuals with limited access to various forms of protest and speech—those in detention. For as long as hunger-strikes have occurred throughout history, governments have force-fed strikers out of a stated obligation to preserve life. Some of the earliest known hunger-strikers, British suffragettes, were force-fed and even died as a result of these invasive procedures during the second half of the 19th century. This Article examines the rationale and necessity behind hunger strikes for imprisoned individuals, the prevailing issues behind force-feeding, the international public response to force-feeding, and the legal normalization of the practice despite public sentiment and condemnation from medical associations. The Article will examine these issues through the lens of two governments that have continued to endorse force-feeding: the United States and Israel. This examination will show that the legal normalization of force-feeding is repressive and runs afoul of international human rights principles and law.

The End of Mass Incarceration: A Blueprint for Transformative Change

By Rasheed Stewart Associate Editor, Vol. 23 He sued the Philadelphia Police Department over 75 times.[1] As a career civil rights and criminal defense attorney he routinely represented individuals subjected to the oppressive forces of racism pervading law enforcement and the criminal justice system.[2] His nationally acclaimed representation of arrested protestors involved with the “Black Lives Matter” movement solidified his reputation among black and brown people as an authentic, hard-nosed movement lawyer.[3] And now, as Philadelphia’s District Attorney, Larry Krasner has managed to put forth a radical, yet replicable platform for ending mass incarceration. Within three months, Krasner has issued several of the most transformative policies that any prosecutor in U.S. history has dared to even imagine. Rather unsurprisingly, Krasner’s new policies have quickly managed to enrage union leaders of the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police,[4] while simultaneously galvanizing influential civil rights activists like Shaun King, in supporting his vision for systemic change.[5] To demonstrate his unrelenting approach to transformative change, Krasner has hit the ground running with a flurry of noteworthy edicts. First, to “broadly reorganize the office’s structure and implement cultural change,” Krasner dismissed 31 members of the office just three days into office, including trial attorneys and several supervisor level staff members.[6] Second, in responding to a judge’s order, Krasner publicly released a secret list of current and former police officers whom prosecutors have sought to keep off the witness stand after a review determined they had a long history of lying, racial bias, or brutality.[7] Moreover, Krasner’s ‘Do Not Call’ list now legitimately sends the foreboding message that cronyism between police officers and ADA’s have no place in an ethically transformed criminal justice system.

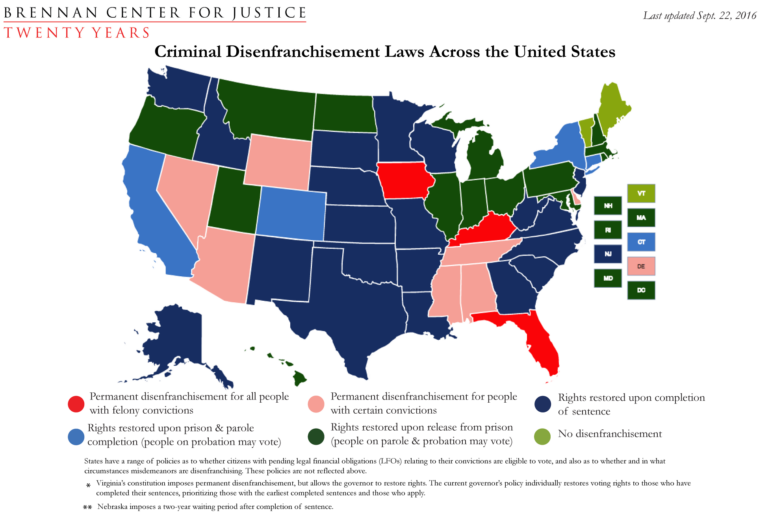

Forever Barred: Examining Felony Disenfranchisement in Florida

By Shanene Frederick Associate Editor, Volume 23 Executive Articles Editor, Volume 24 Desmond Meade was convicted on felony drug and firearm charges back in 2001.[1] Meade, who previously battled drug addiction and experienced homelessness, went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University College of Law.[2] However, his decades-old convictions continue to affect his life today in the form of disenfranchisement. In 2016, Meade could not vote for his wife during her bid for office in the Florida House of Representatives because Florida permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting after they complete their sentences.[3] As the director of Floridians for Fair Democracy, Meade and his team of volunteers have petitioned for over two years in an effort to get a constitutional amendment proposal on Florida’s November 2018 state ballot. [4] Last month, Floridians for Fair Democracy announced that the campaign, Florida Second Chances, had surpassed 799,000 certified signatures, putting it above the required threshold to get on the ballot.[5] If passed, the amendment would restore voting rights to over 1.5 million Floridians, who have been subject to what are arguably the harshest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. [6] The states take various approaches to felony disenfranchisement. As of 2016, all states but Maine and Vermont bar those incarcerated from voting, thirty states restrict those on felony probation from voting, and thirty-four states restrict parolees from voting.[7] Florida is one of twelve states that strip away voting rights post-sentence and post-parole.[8] The effects of Florida’s disenfranchisement scheme are particularly startling: Florida holds 27 percent of the nation’s disenfranchised population, and the total 1.5 million post-sentence disenfranchised individuals make up 48 percent of those who are disenfranchised post-sentence nationally.[9] In 2016, 10.4 percent of Florida’s eligible voting age population was denied the right to vote.[10]

With a Side of Higher Mortality: Prison Food in the United States

By Cleo Hernandez Associate Editor, Volume 23 November begins a holiday season in the United States that is stuffed full of increased attention on food. The average American does seem to gain just under one pound of body weight during the holiday season.[1] However, some individuals avoid this holiday gluttony through no choice of their own.[2] Prisoners in the United States on a day-to-day basis have an extremely different interaction with the “food” they are provided. Research about the nature of prison food in the United States is sparse, but there seems to be a general consensus that an inmate does not receive adequate food.[3] The United States Supreme Court has recognized that the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment in the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution imposes duties on prison officials to provide prisoners with adequate food.[4] In reality many prisoners encounter food that is primarily a product of state legislative choices about funding, and thus prison meal systems will vary widely from state to state and from prison to prison.[5] This means that in some states prisoners are simply not fed enough. In Gordon County, Georgia prisoners only get two meals per day, served at least 10 hours apart.[6] In Butte-Silver Bow County, Montana, prisoner meals averaged between 1,700 and 2,000 calories per day.[7] Furthermore, the nutritional value of the meals seems to be low, with items like margarine, brownies, and cake tacked on to meager meals in order to reach calorie minimums.[8] Certainly, prisoners are not getting the diet rich in a diverse array of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables recommended by United States Department of Agriculture.[9]

The School to Prison Pipeline Comes to Pre-K

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 For years, the startling rates of suspensions and expulsions in America’s public schools have raised concerns for stakeholders across the educational landscape.[1] These disciplinary actions are frequently connected with higher drop-out rates, lower lifetime earnings, and higher rates of incarceration.[2] With African American students facing expulsion and suspension at over three times the rate of their non-Hispanic white peers and American Indian students overrepresented in exclusionary discipline by six times their overall school enrollment, a clear pattern of racial disparity emerges in the current approach to school discipline.[3] Startlingly, in the last few years, research has shown these disparities in school discipline are not confined to K-12, but extend to preschools as well.[4] The first major study exploring suspensions and expulsions in preschools came from Walter S. Gilliam and Golan Shahar in 2006.[5] Their Massachusetts study showed that preschool expulsions occurred at over 34 times the rate of K-12 expulsions and were influenced by larger class sizes, younger enrollees, and elevated “teacher job stress.”[6] While Massachusetts had a relatively low K-12 expulsion rate, these preschool expulsions still occurred at more than 13 times the national K-12 average.[7] Gilliam and Shahar noted that while all states have legal requirements for school attendance starting between ages five and eight, no such law exists for pre-K programs.[8] The authors suggest that, “these laws may reduce expulsion during the K-12 years, because the expulsion would create a legal problem for the parents who would then need to find educational programming for children elsewhere.”[9]The Continuing Significance of the Non-Unanimous Jury Verdict and the Plantation Prison

By Madeleine Jennings Associate Editor, Vol. 22 In 1934, Oregon voters amended their Constitution to allow for non-unanimous jury verdicts in all non-first degree murder and non-capital cases.[1] The Louisiana Constitution requires unanimity only in capital cases.[2] Grounded in xenophobia and anti-Semitism, the Oregon law was passed by a ballot measure following the trial of a Jewish man who, accused of killing two Protestants, had received a lesser manslaughter conviction following a single juror hold-out.[3] The Louisiana iteration was crafted post-Reconstruction to increase convictions of then-freed Blacks, thereby increasing the for-profit labor force.[4] The State had, for decades, leased convicts to plantation owners and, in 1869, leased its prison and all of its inmates to a former major in the Confederate Army, who later moved the prisoners to Angola, the site of the former plantation, named for the country that was once home to its slaves.[5] Once an 8,000-acre plantation, Angola now sits on 18,000 acres—roughly the size of Manhattan—and consumes its own zip code.[6] Today, it is one of the nation’s largest maximum security prisons, and has been named “America’s Bloodiest Prison.”[7]Concealed Motives: Rethinking Fourteenth Amendment and Voting Rights Challenges to Felon Disenfranchisement

Felon disenfranchisement provisions are justified by many Americans under the principle that voting is a privilege to be enjoyed only by upstanding citizens. The provisions are intimately tied, however, to the country’s legacy of racism and systemic disenfranchisement and are at odds with the values of American democracy. In virtually every state, felon disenfranchisement provisions affect the poor and communities of color on a grossly disproportionate scale. Yet to date, most challenges to the provisions under the Equal Protection Clause and Voting Rights Act have been unsuccessful, frustrating proponents of re-enfranchisement and the disenfranchised alike. In light of those failures, is felon disenfranchisement here to stay? This Note contemplates that question, beginning with a comprehensive analysis of the history of felon disenfranchisement provisions in America, tracing their roots to the largescale effort to disenfranchise African Americans during Reconstruction, and identifying ways in which the racism of the past reverberates through practices of disenfranchisement in the present day. Applying this knowledge to understandings of prior case law and recent voting rights litigation, a path forward begins to emerge.