All content categorized with: Social Commentary

Filter

Post List

Digital Colonialism: The 21st Century Scramble for Africa through the Extraction and Control of User Data and the Limitations of Data Protection Laws

As Western technology companies increasingly rely on user data globally, extensive data protection laws and regulations emerged to ensure ethical use of that data. These same protections, however, do not exist uniformly in the resource-rich, infrastructure-poor African countries, where Western tech seeks to establish its presence. These conditions provide an ideal landscape for digital colonialism. Digital colonialism refers to a modern-day “Scramble for Africa” where largescale tech companies extract, analyze, and own user data for profit and market influence with nominal benefit to the data source. Under the guise of altruism, large scale tech companies can use their power and resources to access untapped data on the continent. Scant data protection laws and infrastructure ownership by western tech companies open the door for exploitation of data as a resource for-profit and a myriad of uses including predictive analytics. One may believe that strengthening data protection laws will be a barrier to digital colonialism. However, regardless of their relative strength or weakness, data protection laws have limits. An analysis of Kenya's 2018 data protection bill, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and documented actions of largescale tech companies exemplifies how those limits create several loopholes for continued digital colonialism including, historical violations of data privacy laws; limitations of sanctions; unchecked mass concentration of data, lack of competition enforcement, uninformed consent, and limits to defined nation-state privacy laws.

Power Grab or Not, Expanding Voting Rights is in the Interest of the People, and Democracy

By Mackenzie Walz Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Within days of regaining control of the House of Representatives after an invigorating midterm election, several Democrats vowed to focus their legislative efforts on restoring ethics and transparency in our democratic institutions.[1] As promised, the first bill introduced in the 116th Congress was an ethics reform package titled “For the People.” Also known as HR 1, this act is a sweeping bill aimed at improving three specific aspects of the voting franchise: campaign finance, election security, and voting rights.[2] While Democrats have touted HR 1 as promoting the public interest, Republicans have objected, finding it unnecessary and in furtherance of a partisan agenda.[3] J Christian Adams, president and general counsel of the Public Interest Legal Foundation who served on President Trump’s voter-fraud commission, testified to the House Judiciary Committee that the revisions HR 1 proposes are unnecessary: it has never been easier to vote and it is even difficult to avoid opportunities to register to vote.[4] Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell went even further in his opposition, characterizing the bill as the “Democrat Politician Protection Act.”[5] As one of the most outspoken critics of HR 1, McConnell penned an op-ed for The Washington Post, arguing HR 1 is an “attempt to change the rules of American politics to benefit one party.”[6] While McConnell has taken issue with some provisions more than others, he has continuously expressed that he has no intention of introducing any part of HR 1 in the Senate.[7] Whether or not every provision of HR 1 is necessary or the Act was motivated by partisan interests, studies suggest many provisions of HR 1, individually and collectively, would increase participation among minority voters.[8] There are several structural barriers throughout the political process that impede voter turnout, disproportionately among minority voters: felon disenfranchisement, conducting elections on a Tuesday, arbitrary registration deadlines, and a lack of early voting options. HR 1 seeks to subdue or eliminate these structural barriers, which would increase opportunities for minority participation and, subsequently, increase overall voter turnout.

Countering Violent Extremism Under the Trump Administration: The True Focus is Minority Communities, Not Domestic Extremism

By Mackenzie Walz Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Through the Homeland Security Act of 2002, Congress established the prevention of domestic terrorist attacks as one of the Department of Homeland Security’s primary missions and appropriated ten million dollars “for a countering violent extremism (CVE) initiative to help states and local communities” combat these threats.[1] Pursuant to the Act, in 2011 the Obama Administration created and implemented the “first national strategy” to prevent domestic violent extremism, entitled “Empowering Local Partners to Prevent Violent Extremism in the United States.”[2] Taking a community-based approach, the program was designed to distribute federal funds to local organizations – educational institutions, non-profits, or law enforcement agencies – which would provide community members with the requisite resources and education to identify signs of extremist radicalization.[3] The ultimate goal was for community members and local leaders to develop relationships of trust through this engagement, which would empower community members, once educated, to report any identified signs of extremism.[4] While the program was designed to combat all types of violent extremism, in operation and effect it targeted Muslim-American communities.[5] Instead of building relationships of trust between community members and these local leaders, as it was intended to do, it bred mistrust, as the program in some communities “appeared to be doubling as a means of surveillance.”[6] This mistrust made some members of the Muslim-American community hesitant to reach out to law enforcement officers to report signs of radicalization,[7] rendering the outreach program less effective.The Case Against Police Militarization

We usually think there is a difference between the police and the military. Recently, however, the police have become increasingly militarized – a process which is likely to intensify in coming years. Unsurprisingly, many find this process alarming and call for its reversal. However, while most of the objections to police militarization are framed as instrumental arguments, these arguments are unable to capture the core problem with militarization. This Article remedies this shortcoming by developing a novel and principled argument against police militarization. Contrary to arguments that are preoccupied with the consequences of militarization, the real problem with police militarization is not that it brings about more violence or abuse of authority – though that may very well happen – but that it is based on a presumption of the citizen as a threat, while the liberal order is based on precisely the opposite presumption. A presumption of threat, we argue, assumes that citizens, usually from marginalized communities, pose a threat of such caliber that might require the use of extreme violence. This presumption, communicated symbolically through the deployment of militarized police, marks the policed community as an enemy, and thereby excludes it from the body politic. Crucially, the pervasiveness of police militarization has led to its normalization, thus exacerbating its exclusionary effect. Indeed, whereas the domestic deployment of militaries has always been reserved for exceptional times, the process of police militarization has normalized what was once exceptional.

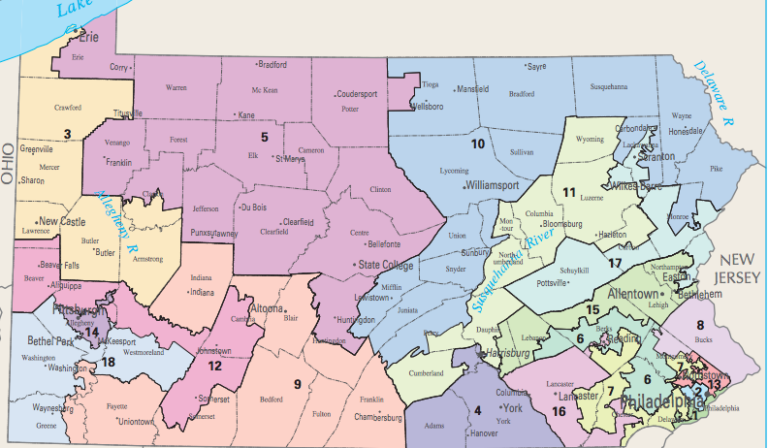

Gerrymandering: Beyond the Partisan Divide

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 Pennsylvania's old Congressional map. Pennsylvania has a long history of a fierce partisan political divisions, due in part to its extremely diverse electorate, geography, and economy.[1] This divide results in massive campaign spending each election cycle and has earned Pennsylvania the label of a battleground or purple state every four years.[2] With this background in mind, it should be no surprise that Pennsylvania is a hub for the practice of gerrymandering which often has a disproportionate effect on communities of color. For partisan gerrymandering, “[t]he playbook is simple: Concentrate as many of your opponents’ votes into a handful of districts as you can, a tactic known as ‘packing.’ Then spread the remainder of those votes thinly across a whole lot of districts, known as ‘cracking.’”[3] Fortunately, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has stepped in, dubbing the Republican created map used over the last six years unconstitutional.[4] In turn, the Court redrew a far more equitable map that may provide a model for nonpartisan redistricting in years to come.[5] The new Congressional map drawn by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in the wake of its recent decision. The new map moves away from the fracturing of communities into disparate districts like the Republican map and attempts to keep counties and municipal areas intact when establishing congressional districts.[6] While the Republican drawn map split 28 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties into separate congressional districts, the new map will only divide 13.[7] An analysis conducted by the Washington Post finds that the new map erases many of the zig-zag lines that were commonplace under the Republican plan, especially in and around urban areas, and eliminates over 1,100 of electoral boarders, a reduction of approximately 37 percent.[8] This focus on compact districts and keeping communities intact when drawing congressional lines is especially notable in Philadelphia, where the new map splits the city into fewer districts.[9] Each of these changes moves towards congressional districts looking “geographically normal,” a goal shared by many nonpartisan experts in the field.[10] Under the new map, districts are defined by strong community ties, unlike the old map where a seafood restaurant held the seventh congressional district “together like a piece of Scotch tape.”[11]

Attacks on Asian Americans

By Ben Cornelius Associate Editor, Volume 23 Kyle Descher was born in Korea, but adopted at a young age by an American couple. [1] Back when he was a college student he and a roommate headed out to a bar after a Washington State University football victory over Oregon. [2] As the pair approached the bar, the remark “fucking Asian” was hurled at Descher. Descher ignored the remark and went about his night.[3] But a few moments later an unknown assailant unleashed a vicious blow that broke Descher’s jaw in two places, and knocked him to the floor, unconscious and bleeding badly.[4] It took three titanium plates to get his jaw back together.[5] His mouth was wired shut.[6] He had to eat through a straw and would wake up several times a night from the throbbing pain.[7] Hate crimes and crimes, and crimes in general, against Asian-Americans have been steadily rising. [8] In Los Angles, an L.A. County Commission on Human Relations report found that crimes targeting Asian-Americans tripled in that county between 2014 and 2015.[9] These sort of attacks also rose in New York City.[10] Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of Asian and Pacific Islander victims of robbery rose from 11.6 percent to 14.2 percent; felonious assault from 5.2 percent to 6.6 percent; and grand larceny from 10.3 percent to 13.5 percent.[11] The robbery statistic is particularly interesting, as robberies overall were down 29 percent over that same period despite the increase in robberies of Asians.[12] Due to likely underreporting, the statistics may be much more troubling. Language barriers, immigration status, and unfamiliarity with the criminal justice system can cause Asians to be hesitant to report crimes.[13] “They look at us as easier targets,” said Karlin Chan, an activist in New York’s Chinatown.[14] Unfortunately, vicious race-based assaults on Asian-Americans are nothing new.[15] Cases of hate crimes against Asian-Americans can be found all the way back to the 1800’s.[16] The white supremacist group ‘Arsonists of the Order of Caucasians’ savagely murdered four Chinese men whom they blamed for taking away jobs from white workers.[17] The victims were tied up, had kerosene poured on them and then were set ablaze.[18] In 1987, a New Jersey gang calling itself the "Dotbusters" vowed to drive East Indians out of Jersey City by vandalizing Indian-owned businesses.[19] The gang also got violent and used bricks to bludgeon a young South Asian male into a coma.[20] Regardless of how many generations a person may have been here, Asians are often seen as the perpetual foreigner hell-bent on stealing jobs and taking over the country.[21]

Can They Do That? (Part 2): End Sanctuary Cities

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 It is not just the long election cycle that is a defining feature of Michigan politics today, but also the impact of term limits on who seeks what office. The current incumbent is forced out by that constitutional measure, and the candidate to replace him is himself subject to the term limits placed on the state House of Representatives. As part of our continuing series, Can They Do That?, today we examine a signature issue from the campaign of Tom Leonard. Speaker Leonard is currently in charge of Michigan’s lower legislative body.[1] He was first elected to represent the 93rd District in 2012,[2] and as a result is ineligible to run again.[3] In keeping with the “up or out” ethos created by these term limits, Speaker Leonard is seeking the office of Attorney General, citing his previous experience as a Genesee County prosecutor and assistant state attorney general during Mike Cox’s tenure.[4] Public safety is a core part of his new campaign, including a promise to “end sanctuary cities”.[5] So, if elected Michigan Attorney General, can he do that? Well, that depends on a number of factors, not least of which is what Speaker Leonard means by “sanctuary city” and by “end”. The most common definition of “sanctuary city” is a city or municipality that has, by rule or ordinance, limited what local law enforcement can do to assist Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) against those with immigration violations.[6] Even within this definition there can be a lot of variety, with cities such as San Francisco that prohibit cooperation with ICE while using city resources,[7] as well as communities like Chester County, Virginia, that simply refuse to automatically detain suspected immigrants.[8]

The Color of Terrorism

By Rasheed Stewart Associate Editor, Volume 23 Mourners create a memorial in Las Vegas to remember those lost after the 2017 shooting. On October 1, 2017, a 64-year-old white American male opened fire on thousands of concertgoers in Las Vegas, Nevada.[1] Over 58 innocent people were murdered and 546 more were injured, instantly making it the deadliest shooting in modern American history.[2] Under Nevada law, terrorism is defined as, “any act that involves the use or attempted use of sabotage, coercion or violence which is intended to cause great bodily harm or death to the general population.”[3] Seemingly, this senseless act of tragic violence consisted of the exact elements Nevada lawmakers intended to criminalize when they created the statute. Undoubtedly, the facts of the Vegas mass shooting should constitute terrorism under the definition of the Nevada statute; however, national media outlets have been quick to opine their own reasoning for why the single deadliest mass shooting in U.S. modern history should not be considered ‘terrorism.’[4] The myriad of reasons they suggest include the contrariness of the Vegas shooting with Oxford’s definition of ‘terrorism,’ of which requires a political aim.[5] Other explanations focus on the FBI’s definition requiring a political objective.[6] Superficially, the media continues to disseminate implicitly biased conclusions to the general population. In turn, these conclusions excuse significantly violent acts caused by white American males, not Islamic State fighters, and condone them as mass shootings, not terrorism. Why? Doubtless, the answer will not appear in the definition of terrorism; nonetheless, there is an unwritten, implicit understanding that the color of ‘terrorism’ is, and always will be, non-white. To further this conclusion, one must look at other examples of similar incidents, and analyze if this claim holds true. On November 5, 2017, a 26-year-old white American male armed with an assault rifle, shot and killed 26 community members, including a child as young as 18 months while they worshipped inside a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas.[7] No motive had been revealed as the investigation proceeded; however, President Trump, like the various U.S. media outlets that effectively continue to control the narrative, tweeted his reasoning for why this occurred by stating the incident was a, “mental health problem of the highest degree,” and not a “guns situation.” [8] Even after a man intentionally walked into a house of worship, and committed the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history,[9] there was not a single utterance of the word ‘terrorism’ or even an act of ‘terror’ that could be found. Of course, President Trump has conceivably memorized the FBI definition for terrorism and refrained from calling the murderer a terrorist because there was no ‘political aim’ present, right? Wrong.

How Should the United Nations Intervene in Libya’s African Migrant Crisis?

By Shanene Frederick Associate Editor, Volume 23 In recent months, increasing media attention has been devoted to the plight of African migrants leaving their home countries in the hopes of reaching Europe.[1] These migrants often give money saved up for the journey to smugglers in Libya, who put them in boats that sail across the Mediterranean, without regard for the migrants’ lives or well-being.[2] Often times, these migrants die during the trips and their bodies wash ashore.[3] As Libya has begun to tighten up security along its coast, reports of smugglers selling African migrants off into slavery have surfaced.[4] What action should be taken in order to help these people of color from death and/or exploitation? One intuitive solution would be the involvement of the United Nations (UN), which is arguably the world’s most influential, powerful, and well-known international organization. The United Nations’ primary goals include maintaining international peace and security and achieving international cooperation in solving international problems.[5] The UN has a wide range of tools in its arsenal that may be used to meet those goals. For example, the UN Security Council has the power vested by the UN Charter to trigger a wide range of obligations binding on the countries of the world.[6] Take the various economic sanctions imposed on North Korea[7] for its testing of nuclear weapons for example, or the sanctions imposed on individuals suspected of supporting terrorism in the aftermath of 9/11.[8] The UN has even engaged in quasi-colonialism, acting as the administrator of territories like East Timor[9] and Kosovo.[10]

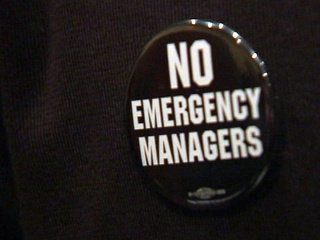

Restoring Democracy in Michigan

By David Bergh Associate Editor, Volume 23 In the wake of the economic destruction wrought by the Great Recession of 2008, many Michigan municipalities fell into dire financial straits.[1] Faced with cities that were sliding into insolvency, the Michigan Legislature passed so-called “emergency manager laws,” in the hope that, by putting the municipality’s finances in the hands of an outside expert, disaster could be averted.[2] Michigan’s existing emergency manager statute was deemed too weak, so the Legislature passed Public Act 4, which was signed by Governor Snyder and went into effect in March 2011.[3] Public Act 4 allowed the State to appoint emergency managers for cities or school districts, and gave them broad power over all financial decisions.[4] This power was then augmented by the passage of Public Act 436, which went into effect in March 2013.[5] Public Act 436, which was given the Orwellian title “Local Financial Stability and Choice Act,” empowered emergency managers to control virtually all aspects of local governance, essentially ending democracy at the local level.[6] Since the first new Emergency Manager Law took effect in 2012, eight cities and three school districts have been brought under state control.[7] The cities brought under state control, which include Detroit, Pontiac, Flint, and Hamtramck, share the common theme of being majority minority.[8] The impact of the Emergency Manager Law on minority communities was so severe, that in 2013 more than half of Michigan’s African American population lived in cities under the control of unelected bureaucrats.[9] Racism has a long history in Michigan - from the KKK nearly getting their candidate elected mayor of Detroit, to the now forgotten 1943 Race Riot during which white mobs, enraged by the presence of black people on Belle Isle, roamed the streets of Detroit unhindered by the police, resulting in the deaths of 24 African Americans.[10] This history is not consigned to the past - cross burnings have occurred in the Detroit area as recently as 2005.[11] Given this history of white supremacy in Michigan, the apparent indifference towards the political rights of black citizens is more than troubling.[12] It is also worth noting that narratives of “financial mismanagement” are false. While local officials deserve some blame for the situation in their cities, the State has been aggressively cutting back on revenue shared with municipalities since 2002.[13] Combined with the impact of the Great Recession, this meant that less affluent communities were simultaneously squeezed by falling tax revenue and declining contributions from the State.[14]