All content categorized with: Housing

Filter

Post List

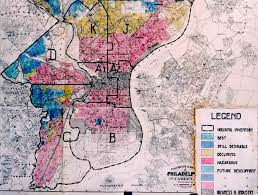

Exploring Mapping Inequality: Redlining Close to Home

By: Eve HastingsAssociate Editor, Vol. 26 Background Mapping Inequality is a website created through the collaboration of three teams at four universities including the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, University of Maryland, and Johns Hopkins University.[1] I was introduced to the website through my Property professor during the…

Chicago’s Construction Boom: Who Is It For?

By Miguel Medina Associate Editor, Vol. 25 Chicago’s Vista Tower, currently under construction. Anyone from Chicago knows quite well that construction is booming. With 33 new high rises in progress, Downtown continues to boast an increasingly packed skyline .”[i] As a summer associate at a…Urban Decolonization

National fair housing legislation opened up higher opportunity neighborhoods to multitudes of middle-class African Americans. In actuality, the FHA offered much less to the millions of poor, Black residents in inner cities than it did to the Black middle class. Partly in response to the FHA’s inability to provide quality housing for low-income blacks, Congress has pursued various mobility strategies designed to facilitate the integration of low-income Blacks into high-opportunity neighborhoods as a resolution to the persistent dilemma of the ghetto. These efforts, too, have had limited success. Now, just over fifty years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act and the Housing Choice Voucher Program (commonly known as Section 8), large numbers of African Americans throughout the country remain geographically isolated in urban ghettos. America’s neighborhoods are deeply segregated and Blacks have been relegated to the worst of them. This isolation has been likened to colonialism of an urban kind. To combat the housing conditions experienced by low-income Blacks, in recent years, housing advocates have reignited a campaign to add “source of income” protection to the federal Fair Housing Act as a means to open up high-opportunity neighborhoods to low-income people of color. This Article offers a critique of overreliance on integration and mobility programs to remedy urban colonialism. Integration’s ineffectiveness as a tool to achieve quality housing for masses of economically-subordinated Blacks has been revealed both in the historically White suburbs and the recently gentrified inner city. Low-income Blacks are welcome in neither place. Thus, this Article argues that focusing modern fair housing policy on the relatively small number of Black people for whom mobility is an option (either through high incomes or federal programs) is shortsighted, given the breadth of need for quality housing in economically-subordinated inner-city communities. As an alternative, this Article proposes, especially in the newly wealthy gentrified cities, that fair housing advocates, led by Black tenants, insist that state and local governments direct significant resources to economically depressed majority-minority neighborhoods and house residents equitably. This process of equitable distribution of local government resources across an entire jurisdiction, including in majority-minority neighborhoods, may be a critical step towards urban decolonization.

The Color of Blight: Michigan’s Troubled History of Urban Renewal Complicates Detroit’s Comeback

By David Bergh Associate Editor, Volume 23 Online Publications Editor, Volume 24 The governmental power of eminent domain has deep roots in the Anglo-American legal tradition. Early English law held that the power to expropriate land was inherent in the Crown’s sovereign authority.[1] As an element of the Crown’s sovereignty, this power was essentially limitless - the King or Queen could take land without compensation, as William I did following the Norman Conquest.[2] The requirement that compensation be paid developed as the absolute power of the Crown waned.[3] This legal doctrine was little altered in the early years of the United States. The Michigan Constitution of 1835 contains no affirmative grant of the power to use eminent domain, only the requirement that property could not be taken “without just compensation therefor.”[4] The fact that the power of eminent domain inhered in the residual sovereignty of the states was endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1878.[5]

Can They Do That? (Part 3): Reversing Modern-Day Redlining

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 Production Editor, Volume 24 Patrick Miles Jr. - Michigan candidate for Attorney General Detroit remains the most segregated metropolitan areas in the United States.[1] This is in part thanks to historical practices such as “redlining” where majority African-American neighborhoods were deemed “too risky” for mortgage lending.[2] Though overt discrimination in housing has been outlawed[3], the systems created for that purpose often remain, in whole or in part. One Democratic candidate for Michigan Attorney General, Pat Miles, has pledged to use the office to combat modern-day redlining.[4] Patrick Miles Jr., who prefers to go by Pat, is the former U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Michigan, serving from 2012 to 2017. Prior to that appointment, his experience was largely in private sector and telecommunications law. As part of our ongoing series examining the campaign pledges of candidates for that office, we have to ask: can he do that? The study Mr. Miles cited in his pledge to defend consumers was conducted by Reveal, a project of the Center for Investigative Journalism. Its analysis of data from 61 metro areas across 2015 and 2016 resulted in a blunt conclusion: “Fifty years after the federal Fair Housing Act banned racial discrimination in lending, African Americans and Latinos continue to be routinely denied conventional mortgage loans at a rate far higher than their white counterparts.”[5] In Detroit, that trend meant an African-American applicant was almost twice as likely to be denied a conventional home mortgage.[6] Defenders of current mortgage practices point to what they believe are flaws in that data. They argue that high rejection rates are a result of large lenders and technology, making applying for a mortgage easier and leading to more applicants with subpar credit.[7] Yet this explanation ignores that federal housing policy codified racial minority populations as a lending risk for years, and those policies’ effects persist today.[8] Without the access to long-term investment and wealth from generations ago, today’s minority borrowers are still subject to these trends.[9]Reverse Redlining and the Destruction of Minority Wealth

By Asma Husain Associate Editor, Vol. 22 In 2012, Wells Fargo entered into a $175 million settlement after being accused of pursuing discriminatory lending practices. Specifically, the bank and its subsidiaries were accused of charging African Americans and Latinos higher rates and fees on mortgages than their White counterparts.Inclusionary housing: a legitimate response to rising segregation

By the Vol. 21 Associate Editorial Staff America’s cities remain highly segregated along both class and racial lines. According to a recent study, between 1970 and 2010, segregation rose within metropolitan areas among school districts. Segregation by family income rose by roughly 20 percent when looking only at families…Supreme Court should allow disparate-impact Fair Housing Act claims

By Luis Gomez, Associate Editor, Vol. 20 Intentional racial discrimination is difficult to prove in suits like the one involving the nonprofit Inclusive Communities Project and the Texas Department of Housing, which went before the U.S. Supreme Court on January 21st. Proving the discriminatory consequences of policies implemented by government…Complicating the Gentrification Discussion

By Andrew Goddeeris, Online Publications Editor, Vol. 20 “Gentrification” is simultaneously (1) difficult for urban planners and economists to quantify and explain and (2) commonly debated by people of a wide range of backgrounds and experiences. It takes on different connotations for different people, but one common image is that…‘Separate and unequal’: Racial segregation flourishes in US suburbs

By Luis Gomez, Associate Editor Vol. 20 America’s suburbs are displaying the same cycle of racial segregation and inequality that have afflicted major city centers for decades. This phenomenon is due to the changing racial landscape of America’s suburbs. Logan, a Brown University sociologist, discusses the racial division in his…