All content categorized with: Health

Filter

Post List

Toward a Race-Conscious Critique of Mental Health-Related Exclusionary Immigration Laws

This Article employs the emergent analytical framework of Dis/ability Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) to offer a race-conscious critique of a set of immigration laws that have been left out of the story of race-based immigrant exclusion in the United States—namely, the laws that exclude immigrants based on mental health-related grounds. By centering the influence of the white supremacist, racist,and ableist ideologies of the eugenics movement in shaping mental health-related exclusionary immigration laws, this Article locates the roots of these restrictive laws in the desire to protect the purity and homogeneity of the white Anglo- Saxon race against the threat of racially inferior, undesirable, and unassimilable immigrants. Moreover, by using a DisCrit framework to critique today’s mental health-related exclusionary law, INA § 212(a)(1)(A)(iii), this Article reveals how this law carries forward the white supremacist, racist, and ableist ideologies of eugenics into the present in order to shape ideas of citizenship and belonging. The ultimate goal of the Article is to broaden the conceptualization of race-based immigrant exclusion to encompass mental health-related immigrant exclusion, while demonstrating the utility of DisCrit as an exploratory analytical tool to examine the intersections of race and disability within immigration law.Medical Violence, Obstetric Racism, and the Limits of Informed Consent for Black Women

This Essay critically examines how medicine actively engages in the reproductive subordination of Black women. In obstetrics, particularly, Black women must contend with both gender and race subordination. Early American gynecology treated Black women as expendable clinical material for its institutional needs. This medical violence was animated by biological racism and the legal and economic exigencies of the antebellum era. Medical racism continues to animate Black women’s navigation of and their dehumanization within obstetrics. Today, the racial disparities in cesarean sections illustrate that Black women are simultaneously overmedicalized and medically neglected—an extension of historical medical practices rooted in the logic of biological race. Though the principle of informed consent traditionally protects the rights of autonomy, bodily integrity, and well-being, medicine nevertheless routinely subjects Black women to medically unnecessary procedures. This Essay adopts the framework of obstetric racism to analyze Black women’s overmedicalization as a site of reproductive subordination. It thus offers a critical interdisciplinary and intersectional lens to broader conversations on race in reproduction and maternal health.

Showing the Government CARES – Using Prior Crises to Support Minority Communities

By Lexi Wung Associate Editor, Vol. 26 llustration from rawpixel.com At the beginning of my second year of law school I tested positive for COVID-19. I spent my first week of classes isolating in remote apartment housing on Michigan’s north campus. Aside from mild symptoms and lingering fatigue, I…Reproductive Justice for Black Mothers: The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act and the Work We Have Left to Do

By Meredith Reynolds Associate Editor, Vol. 24 The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was signed into law in December 2018.[1] This legislation has been years in the making[2] and part of a growing “birth equity movement” confronting how racism, poverty, and other social inequities are impacting mothers of color and their children.[3] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”) has tracked a significant increase in pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births from 7.2 in 1987 to 18.0 in 2014 for all women in the United States.[4] This reality puts the United States at the bottom when comparing maternal health outcomes across high-income countries.[5] While there are many factors potentially contributing to this drastic rise, including changes in data collection over time and an increase in women with chronic health conditions, one fact is clear: mothers of color, and black mothers in particular, are the ones disproportionately losing their lives.[6] According to the CDC’s 2011-14 data, while the number of deaths per 100,000 live births for white women was 12.4, the number for black women was a staggering 40.0, and the average for women of other races was 17.8.[7] Even when controlling for variables like education and socioeconomic status, black women are more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications.[8]

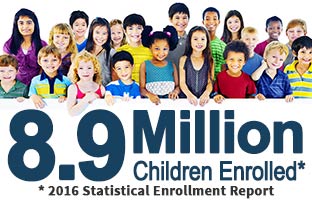

The Children’s Health Insurance Program at Twenty: Essential yet Expired

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) has been a triumph of effective bipartisan policy for the last two decades.[1] Unfortunately, the program which has helped to lower the uninsured rate for America’s kids, from 14 percent in 1997 to just 4.5 as recently as 2015, was allowed to expire this Fall.[2] While CHIP is an essential program for a diverse array of families, it has been especially impactful in communities of color. In tandem with Medicaid, CHIP covers nearly 40 percent of kids in the United States, and of those children benefitting from the program, nearly 60 percent are African American or Hispanic.[3] If Congress fails to act, states will soon run out of funding and millions of children could be at risk of losing coverage.[4] This would exacerbate racial disparities in access to healthcare and the negative outcomes that follow from a lack of coverage for kids. Implemented during the Clinton administration, CHIP provides coverage for children in families whose incomes are above the Medicaid thresholds but would otherwise struggle to afford insurance.[5] “While CHIP income eligibility levels vary by state, about 90 percent of children covered are in families earning 200 percent of poverty or less ($40,840 for a family of three). CHIP covers children up to age 19. States have the option to cover pregnant women, and 19 do so.”[6] From the perspective of pediatricians, CHIP both saves and improves the lives of the children and families it covers. Dorothy Novick, a pediatrician at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, notes, Every day I see patients in my practice who stand to lose their health care if Congress does not act to extend CHIP funding. Consider my patient who grew up in foster care, put herself through college and now earns a living as a freelanceclothing designer. She is now a mother herself, and I treat her children. Her 1-year-old son has asthma and her 3-year-old daughter has a peanut allergy. They are able to follow up with me every three months and keep a ready supply of lifesaving medications because they qualify for CHIP. Or consider the dad with a hearing impairment whose wife passed away two years ago. He supports his teenage daughters by working as a line cook during the day and a parking attendant at night. He sends the girls to a parochial school. He lost their Medicaid when he was given extra hours at his restaurant last year. But I still see them because they qualify for CHIP.[7]Black Health Matters: Disparities, Community Health, and Interest Convergence

Health disparities represent a significant strand in the fabric of racial injustice in the United States, one that has proven exceptionally durable. Many millions of dollars have been invested in addressing racial disparities over the past three decades. Researchers have identified disparities, unpacked their causes, and tracked their trajectories, with only limited progress in narrowing the health gap between whites and racial and ethnic minorities. The implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the movement toward value-based payment methods for health care may supply a new avenue for addressing disparities. This Article argues that the ACA’s requirement that tax-exempt hospitals assess the health needs of their communities and take steps to address those needs presents a valuable opportunity to engage hospitals as partners in efforts to reduce racial health disparities. Whether hospitals will focus on disparities as they assess their communities’ health needs, however, is uncertain; preliminary reviews of hospitals’ initial compliance with the new requirement suggest that most did not. Relying on Professor Derrick Bell’s interest-convergence theory, this Article explores how hospitals’ economic interests may converge with interests in racial health justice. It presents two examples of interventions that could reduce disparities while saving hospitals money. The Article closes by identifying steps that health justice advocates, the federal government, and researchers should take to help, in Professor Bell’s words, “forge [the] fortuity” of interest convergence between hospitals and advocates for racial justice, and lead to progress in eliminating racial health disparities.Reproductive Justice and Black Lives Matter: Remembering the roots of RJ

By Dana Ziegler Associate Editor, Vol. 21 Online Publications Editor, Vol. 22 On February 9, 2016, advocates from Black Lives Matter (BLM), New Voices for Reproductive Justice, and Trust Black Women held a conference call to reassert the connection between the BLM and reproductive justice movements while…

“Criminalized pregnancy” hurts poor and minority women most, faces legal challenges

By Dana Ziegler Associate Editor, Vol. 21 In March 2015, Purvi Patel, an Asian-American woman from Indiana, became the first woman in the U.S. to be convicted and sentenced for feticide. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison for feticide and neglect of a dependent after…

Race, mental illness, and Kamilah Brock

By Dana Ziegler Associate Editor, Vol. 21 Last week, a shocking news story made headlines in the online news circuit. Kamilah Brock, a Black businesswoman living in New York City, was involuntarily committed to a mental institution by police after trying to reclaim her impounded BMW in…Breastfeeding on a Nickel and a Dime: Why the Affordable Care Act’s Nursing Mothers Amendment Won’t Help Low-Wage Workers

As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (also known as “Obamacare”), Congress passed a new law requiring employers to provide accommodation to working mothers who want to express breast milk while at work. This accommodation requirement is a step forward from the preceding legal regime, under which federal courts consistently found that “lactation discrimination” did not constitute sex discrimination. But this Article predicts that the new law will nevertheless fall short of guaranteeing all women the ability to work while breastfeeding. The generality of the Act’s brief provisions, along with the broad discretion it assigns to employers to determine the details of the accommodation provided, make it likely that class- and race-inflected attitudes towards both breastfeeding and women’s roles will influence employer (and possibly judicial) decisions in this area. Examining psychological studies of popular attitudes towards breastfeeding, as well as the history of women’s relationships to work, this Article concludes that both are likely to negatively affect low-income women seeking accommodation under the Act, perhaps especially those who are African-American. In short, the new law could lead to a two-tiered system of breastfeeding access, encouraging employers to grant generous accommodations to economically privileged women and increasing the social pressure on low-income women to breastfeed, without meaningfully improving the latter group’s ability to do so.