All content categorized with: Education

Filter

Post List

Personal Reflection on How Race is Absent from the Law School Curriculum

by Miguel Suarez Medina Associate Editor, Vol. 25 Current law students are a major component of a law school’s recruitment process. Admissions offices depend on student participation, particularly students of color, to help convince talented candidates to apply and eventually attend. Michigan Law is no expectation. Most people I…

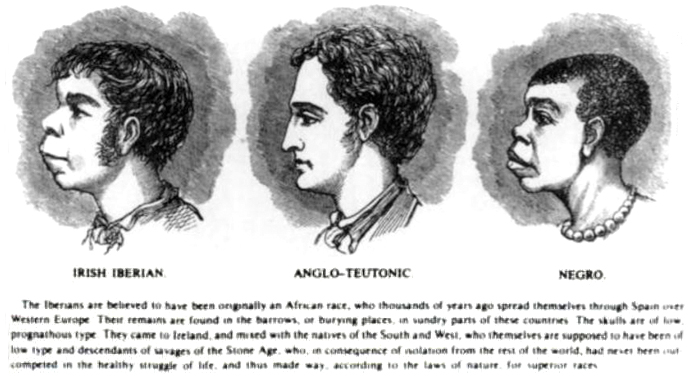

Combatting White Supremacy: The Pressing Need to Make the Baseless “Scientific” Origins of Race and Their Place in Society Part of American Curriculum

By Matthew Fellows Associate Editor, Vol. 25 Race is a human invention. Although made up, race theories in their inception were offered and accepted as constituting natural scientific fact. The hierarchies created out of pen and paper articulated what people thought was a proper arrangement of the…The Right to Be and Become: Black Home-Educators as Child Privacy Protectors

The right to privacy is one of the most fundamental rights in American jurisprudence. In 1890, Samuel D. Warren and Louis D. Brandeis conceptualized the right to privacy as the right to be let alone and inspired privacy jurisprudence that tracked their initial description. Warren and Brandeis conceptualized further that this right was not exclusively meant to protect one’s body or physical property. Privacy rights were protective of “the products and the processes of the mind” and the “inviolate personality.” Privacy was further understood to protect the ability to “live one’s life as one chooses, free from assault, intrusion or invasion except as can be justified by the clear needs of community living under a government of law.” Case law supported and extended their theorization by recognizing that privacy is essentially bound up in an individual’s ability to live a self-authored and self-curated life without unnecessary intrusions and distractions. Hence, privacy may be viewed as the right of individuals to be and become themselves. This right is well-established; however, scholars have vastly undertheorized the right to privacy as it intersects with racial discrimination and childhood. Specifically, the ways in which racial discrimination strips Black people—and therefore Black children—of privacy rights and protections, and the ways in which Black people reclaim and reshape those rights and protections remain a dynamic and fertile space, ripe for exploration yet unacknowledged by privacy law scholars. The most vulnerable members of the Black population, children, rely on their parents to protect their rights until they are capable of doing so themselves. Still, the American education system exposes Black children to racial discrimination that results in life-long injuries ranging from the psychological harms of daily racial micro-aggressions and assaults, to disproportionate exclusionary discipline and juvenile incarceration. One response to these ongoing and often traumatic incursions is a growing number of Black parents have decided to remove their children from traditional school settings. Instead, these parents provide their children with home-education in order to protect their children’s right to be and become in childhood.

Students Against Fair Admissions: The Continued War on Affirmative Action

By Kyle Pham Associate Editor, Vol. 25 The Harvard Yard Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. Harvard is a federal lawsuit challenging Harvard University’s consideration of race and ethnicity in its undergraduate admissions process.[1] While U.S. District Judge Allison D. Boroughs recently ruled in favor…Incorporating Social Justice into the 1L Legal Writing Course: A Tool for Empowering Students of Color and of Historically Marginalized Groups and Improving Learning

The media reports of police shootings of unarmed Black men and women; unprovoked attacks on innocent Jews, Muslims, religious minority groups, and LGBTQ persons; and current pervasive, divisive, and misogynistic rhetoric all cause fear and anxiety in impacted communities and frustrate other concerned citizens. Law students, and especially law students of color and of historically marginalized groups, are often directly or indirectly impacted by these reports and discrimination in all its iterations. As a result, they are stressed because they are fearful and anxious. Research shows that stress impairs learning and cognition. Research also shows that beneficial changes are made in the brain, and learning and cognition improve when students are empowered and motivated by their lessons. Incorporating issues of social justice into the first-year legal writing course benefits all students by equipping them with the knowledge and practical skills to address issues of social injustice and to affect social change. Incorporating issues of social justice into the first-year legal writing course has the added benefit of contributing to a learning environment that permits law students of color and of historically marginalized groups to learn more successfully by reducing stress, altering their perception of control over psychosocial stressors, building positive emotions, increasing confidence, and motivating them to learn.

New Report on the School Funding Gap Highlights The Continuing Dangers of School Segregation

By Rose Lapp Associate Editor, Vol. 24 “Good schools can’t solve structural inequality on their own, but neither can it be solved without them. Without an effective education, our children’s futures are all but guaranteed to succumb to the imposed conditions of their lineage and location.”[1] So warns…

The Role of Transactional Law Clinics in Promoting Social Justice

By Leah Duncan Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Access to justice is arguably one of the biggest problems facing the legal profession.[1] As Brian Price, director of Harvard Law School’s Transactional Law Clinics, puts it, “[w]hen people try to navigate the legal world without representation, deterred by the cost, they are at a structural disadvantage compared to those who know the rules of the game.”[2] In recent decades, law clinics have played a significant role in addressing the gap in services to clients who lack the means to afford high legal fees. During the early years of legal clinics, most law schools legal clinic offerings focused on civil and criminal litigation. But over the past few years, there has been an increasing instance of transactional clinics which focus on providing legal aid to low-income entrepreneurs, small businesses, and other community-based organizations.[3] As a tool to solve the access to justice crisis, community organizers use various strategies to empower community members to direct their own future. While civil and criminal litigation clinics have secured their space in the access to justice toolbox, professors, scholars, and students alike have begun to engage in serious dialogue about what role, if any, transactional law clinics can play. Transactional law clinics primarily focus on assisting small businesses and entrepreneurs in business formation, contract drafting and other types of transactions. These transactional law clinics, like the University of Michigan Law Entrepreneurship Clinic, point to the value of free and reduced fee transactional services for small businesses and low-income entrepreneurs who may not otherwise receive legal aid. To this end, this article explores justifications for the inclusion of transactional clinics in the fight for access to justice and provides insight to strategies for its inclusion.

Improving Michigan’s School Expulsion Policy Would Help Cut School to Prison Pipeline

By Kara Crutcher Associate Editor, Vol. 24 There is a strong correlation between the amount of time that K-12 students spend out of school for disciplinary reasons, and the likelihood of them ending up in the correctional system. This concept, known as the school to prison pipeline, is heavily present in the lives of black and brown students that are subject to harsh disciplinary action more so than their white counterparts.[1] Until 2016, the Michigan education system was known for its zero-tolerance policies.[2] Zero tolerance led at least twelve Michigan school districts to over-suspend students of color.[3] Under these policies, school boards had no discretion over the disciplinary action taken towards a student that brought a dangerous weapon to school, engaged in criminal sexual conduct, committed arson, or physically assaulted a staff member or school volunteer. Rather, if a student engaged in any of these behaviors, they were subject to mandatory expulsion, where no other public school in the district would be required to accept them as a new student.[4] This left many young people of color in an extremely vulnerable position, as there is a greater chance that they will become disengaged in their education, and become involved in activities that can lead to incarceration.[5] In an effort to use a more holistic approach in K-12 discipline, Michigan representatives introduced Public Act No. 360[6] in 2016. The act “creates a rebuttable presumption that a suspension of 10 days or more and/or an expulsion”[7] is unjustified unless seven factors are considered. These factors include a student's age, disciplinary history, learning and/or emotional disabilities, the seriousness of behavior, whether the behavior posed a safety risk, whether restorative practices had been already utilized, and whether a lesser intervention would address the behavior.[8] The act went into effect August 1, 2017.[9]

Department of Education Reopens Anti-Discrimination Case, Sparks Controversy

By Rose Lapp Associate Editor, Volume 24 In 2011, The Zionist Organization of America filed a religious discrimination claim against Rutgers University with the Department of Education Office of Civil Rights (“OCR”). The complaint had three claims. One of these claims, the one being addressed by the Department of Education and by this piece, arose out of an event held on campus by a pro-Palestinian group.[1] Allegedly, there was originally free admission to the event, but the organizers began charging admission “only after [they] observed ‘150 Zionists’ who ‘just showed up.’”[2] Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, OCR has jurisdiction over discrimination on the basis of race, color and national origin.[3] Under Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972, the office has jurisdiction over sex discrimination claims.[4] Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975 gives OCR jurisdiction over discrimination on the basis of disability and discrimination on the basis of age, respectively.[5] The office does not, however, have jurisdiction over religious discrimination claims. In 2014, on the grounds that there was insufficient evidence of discrimination on the basis of national origin, the Department of Education closed the case.[6] However, now four years later, Kenneth Marcus, the current Assistant Secretary for the Office of Civil Rights at the Department of Education, has reopened the case.[7] He has indicated that he will reexamine the complaint as “possible discrimination against an ethnic group,”[8] and has expanded the definition of anti-Semitism in the OCR context to a “working definition” that is used in other government agencies.[9] This definition includes “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” and “applying double standards by requiring of it a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation.”[10] These changes will likely have serious consequences for discrimination claims brought by Jewish students.Betsy DeVos, School Choice, and the Resegregation of American Public Schools

By Laura Page Associate Editor, Vol. 22 The Senate confirmation hearing of Betsy DeVos, the President’s nominee for Secretary of Education, was one of the most contentious and heated in recent history.[1] Critics contend that the billionaire Republican donor has no experience in public education—neither she nor her…