All content tagged with: Women’s Rights

Filter

Post List

MJRL Statement on SCOTUS Overturning Roe v. Wade

On Friday, the Supreme Court officially overturned Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Dobbs eradicates what has been the law of the land for nearly half a century: that the Constitution protects the fundamental right to an abortion. This decision has…

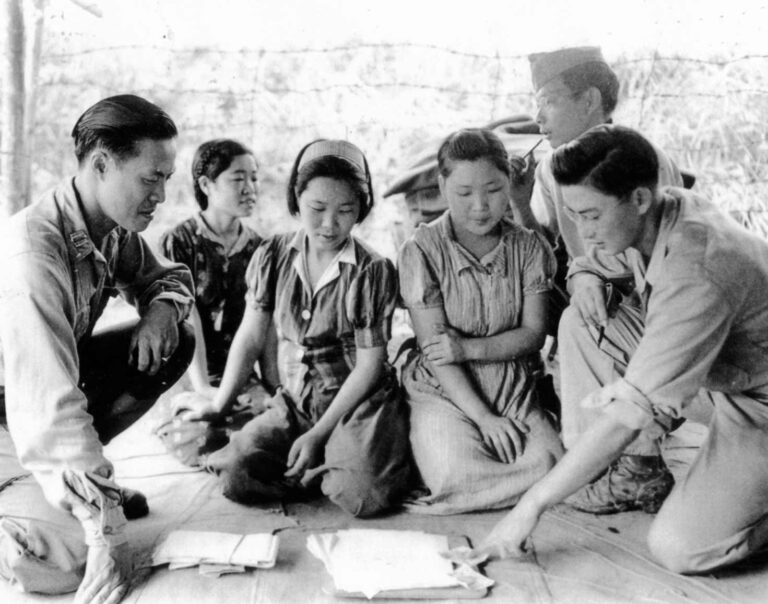

Reaction against the Denial of Comfort Women’s Voices and Truth

By Karly JungAssociate Editor, Vol. 26 Across the globe, academics and activists mobilized to thoroughly examine a Harvard professor’s characterization of “comfort women” as prostitutes.[1] So-called “comfort women” consisted of women and girls from various countries (though primarily from Korea, a colony of Japan at the time) who…Medical Violence, Obstetric Racism, and the Limits of Informed Consent for Black Women

This Essay critically examines how medicine actively engages in the reproductive subordination of Black women. In obstetrics, particularly, Black women must contend with both gender and race subordination. Early American gynecology treated Black women as expendable clinical material for its institutional needs. This medical violence was animated by biological racism and the legal and economic exigencies of the antebellum era. Medical racism continues to animate Black women’s navigation of and their dehumanization within obstetrics. Today, the racial disparities in cesarean sections illustrate that Black women are simultaneously overmedicalized and medically neglected—an extension of historical medical practices rooted in the logic of biological race. Though the principle of informed consent traditionally protects the rights of autonomy, bodily integrity, and well-being, medicine nevertheless routinely subjects Black women to medically unnecessary procedures. This Essay adopts the framework of obstetric racism to analyze Black women’s overmedicalization as a site of reproductive subordination. It thus offers a critical interdisciplinary and intersectional lens to broader conversations on race in reproduction and maternal health.

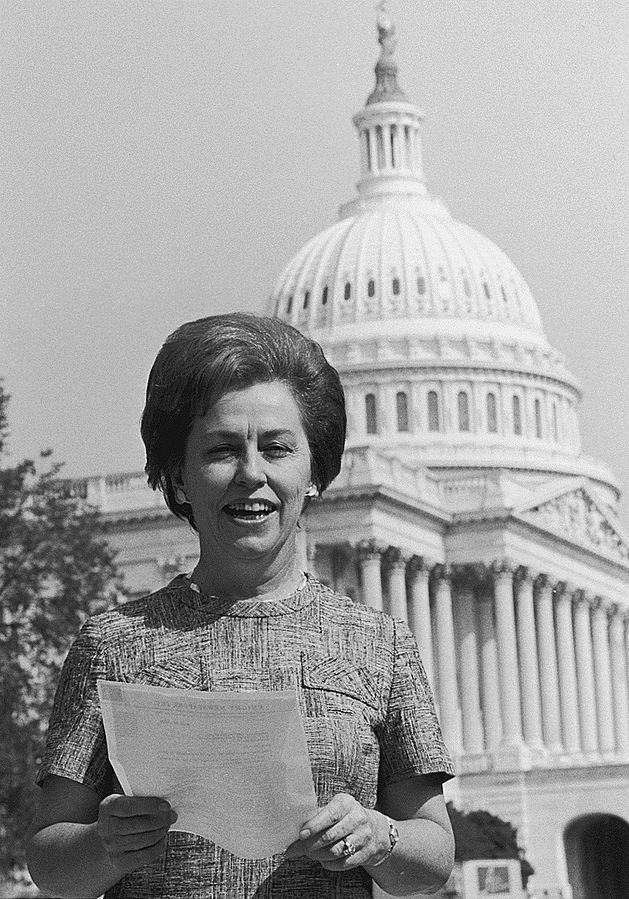

The Twenty-Eighth Amendment is Here

by Tamar Alexanian Associate Editor, Vol. 25 In January, Virginia became the thirty-eighth state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). But the history of the ERA spans nearly a century, and the fight isn’t over yet. What does the ERA say? The original text of the ERA was…Regarding Narrative Justice, Womxn

The story within this article explores how narrative justice can be applied as a form of advocacy for persons seeking access to justice. The questions—what is narrative justice? How do we define it?—deserve a separate space, which will be shared in a forthcoming article. Meanwhile, in short, narrative justice is the power of the word—written, spoken, articulated with the emotion or experience of an individual or collective, to shape or express reaction to law and policy.Reproductive Justice for Black Mothers: The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act and the Work We Have Left to Do

By Meredith Reynolds Associate Editor, Vol. 24 The Preventing Maternal Deaths Act was signed into law in December 2018.[1] This legislation has been years in the making[2] and part of a growing “birth equity movement” confronting how racism, poverty, and other social inequities are impacting mothers of color and their children.[3] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (“CDC”) has tracked a significant increase in pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births from 7.2 in 1987 to 18.0 in 2014 for all women in the United States.[4] This reality puts the United States at the bottom when comparing maternal health outcomes across high-income countries.[5] While there are many factors potentially contributing to this drastic rise, including changes in data collection over time and an increase in women with chronic health conditions, one fact is clear: mothers of color, and black mothers in particular, are the ones disproportionately losing their lives.[6] According to the CDC’s 2011-14 data, while the number of deaths per 100,000 live births for white women was 12.4, the number for black women was a staggering 40.0, and the average for women of other races was 17.8.[7] Even when controlling for variables like education and socioeconomic status, black women are more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications.[8]

An Overlooked Consequence of the Government Shutdown: The Expiration of the Violence Against Women Act

By Mackenzie Walz Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On December 22nd, 2018, the United States government entered a partial shutdown after Congress and the White House failed to reach an agreement over the amount of funding to appropriate for the construction of a wall at our southern border. Since that moment, the national conversation has focused on the plight of immigrants and of federal workers. But the shutdown had another dire consequence, which, despite the effort of some Senators,[1] went virtually unnoticed: the Violence Against Women Act expired,[2] which left the fate of several grant programs critical to the protection of many Native American[3] women uncertain. The Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) was passed by Congress in 1994 in response to persistent advocacy from survivors, advocates, police, attorneys, and scientists to address the prevalence of violence plaguing women throughout the country.[4] After years of blatant inattentiveness to this violence, the passage and substance of VAWA was revolutionary.[5] The Act aims to reduce domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, and stalking by increasing the availability of victim services and by holding offenders accountable.[6] These objectives are carried out through the appropriation and disbursement of funds to programs run by independent nonprofit organizations or state, local, and tribal governments. Congress established the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) within the Department of Justice to administer the grant programs. While four of the grant programs are considered “formula grant programs” and are funded through congressional appropriation, the remainder of the grant programs are discretionary, meaning OVW has the authority to determine the scope, eligibility, and funding of these programs.[7] VAWA has reduced the prevalence of domestic violence throughout the United States, but it has not eliminated it. Domestic violence still affects people from all different socioeconomic, racial, religious, and sexual identity backgrounds.[8] According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, one in three women will experience intimate partner violence in their lifetime.[9]

Do Indigent and Incarcerated Women Have a Real Right to Reproductive Justice?

By Hira Baig Associate Editor, Volume 23 Reproductive justice is not just concerned with women having access to the healthcare they need, it is also concerned with the disparate impact caused by restrictions on reproductive healthcare. Historically, the more restrictions the Court allows on abortion, the more challenging it becomes for indigent women, women of color, and incarcerated women to get the healthcare they need. In order to achieve reproductive justice, scholars and advocates alike ought to think of a comprehensive way to help all women access the reproductive healthcare they need before, during, and even after pregnancy. Currently, the doctrine surrounding reproductive healthcare, primarily abortion, does not account for women’s social contexts and allows restrictions that keep minority and indigent women from enjoying equal protection of the laws. It comes as no surprise that indigent women face severe restrictions when trying to access abortion. Incarcerated women, however, face even greater hurdles. Today, prisons and jails in the United States confine approximately 206,000 women.[1] Approximately 6-10% of women are already pregnant when they enter a prison or jail.[2] Doctor visits for pregnant women in prison are infrequent, with only 54% of women who reported being pregnant in state prisons receiving pregnancy care.[3]

“Criminalized pregnancy” hurts poor and minority women most, faces legal challenges

By Dana Ziegler Associate Editor, Vol. 21 In March 2015, Purvi Patel, an Asian-American woman from Indiana, became the first woman in the U.S. to be convicted and sentenced for feticide. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison for feticide and neglect of a dependent after…Coercive Assimilationism: The Perils of Muslim Women’s Identity Performance in the Workplace

Should employees have the legal right to “be themselves” at work? Most Americans would answer in the negative because work is a privilege, not an entitlement. But what if being oneself entails behaviors, mannerisms, and values integrally linked to the employee’s gender, race, or religion? And what if the basis for the employer’s workplace rules and professionalism standards rely on negative racial, ethnic or gender stereotypes that disparately impact some employees over others? Currently, Title VII fails to take into account such forms of second-generation discrimination, thereby limiting statutory protections to phenotypical or morphological bases. Drawing on social psychology and antidiscrimination literature, this Article argues that in order for courts to keep up with discrimination they should expansively interpret Title VII to address identity-based discrimination rooted in negative implicit stereotypes of low status groups. In doing so, the Article brings to the forefront Muslim women’s identity performance at the intersection of religion, race, gender, and ethnicity—a topic marginalized in the performativity literature. I argue that Muslim female employees at the intersection of conflicting stereotypes and contradictory identity performance pressures associated with gender, race, and religion are caught in a triple bind that leaves them worse off irrespective of their efforts to accommodate or reject coercive assimilationism at work.