All content tagged with: Racial Analogues

Filter

Post List

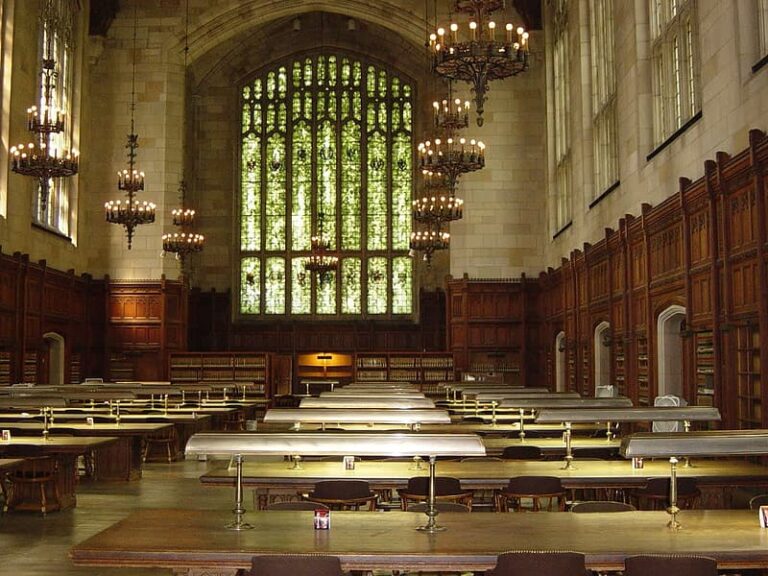

Personal Reflection on How Race is Absent from the Law School Curriculum

by Miguel Suarez Medina Associate Editor, Vol. 25 Current law students are a major component of a law school’s recruitment process. Admissions offices depend on student participation, particularly students of color, to help convince talented candidates to apply and eventually attend. Michigan Law is no expectation. Most people I…

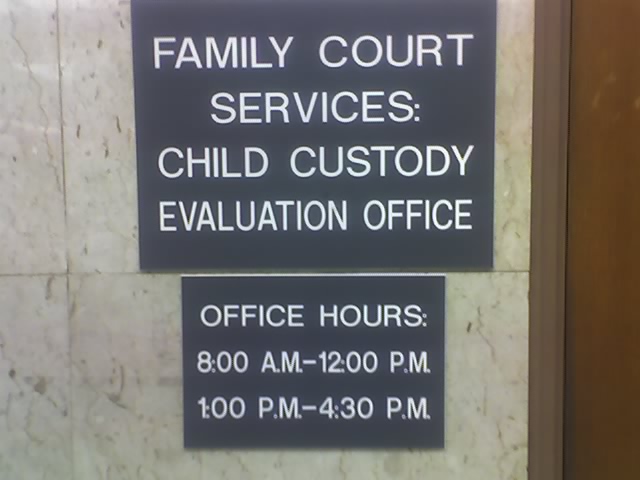

How the Child Welfare System Targets Black Families

By Raul Noguera-McElroy Associate Editor, Vol. 25 Part I: Overview This fall, I enrolled in Race and the Law, a class that examines how the United States’ legal system oppresses various ethnic and/or racial minority groups. The course gave a passing mention of how the child welfare system fits…

Call It What It Is: Environmental Racism

By Kara Crutcher Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On March 15th, young people walked out of classrooms across the globe in the name of environmental justice. Following in the footsteps of 16-year-old Greta Thunberg – who’s been protesting Swedish lawmakers’ failure to implement the Paris Climate Agreement – young activists took to the streets to further emphasize that not only is climate change real, but that we need to take it more seriously as a global community.[2] According to GreenAction, a grassroots organization based out of California dedicated to environmental justice work, environmental racism is defined as “the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on people of color.”[3] This concept is exemplified by two major events within the past two decades – the effects of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and the Flint Water Crisis. In 2013 almost 80% of 9th Ward in New Orleans still had not returned to their homes because the city’s reconstruction efforts were lacking. Flint’s residents drank contaminated water for at least two years due to eroding pipes, highly contaminated water,[5] and a disregard for resident’s safety. Just like those affected in 9th Ward in New Orleans, Flint’s residents are overwhelmingly Black.

New Report on the School Funding Gap Highlights The Continuing Dangers of School Segregation

By Rose Lapp Associate Editor, Vol. 24 “Good schools can’t solve structural inequality on their own, but neither can it be solved without them. Without an effective education, our children’s futures are all but guaranteed to succumb to the imposed conditions of their lineage and location.”[1] So warns…

What the Passage of Michigan’s Proposal One Means for Black and Latinx People

By Elizabeth Morales-Saucedo Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On November 6, 2018, 56% of Michigan voters supported the passage of Proposal One approving the legalization of recreational use and possession of marijuana by persons 21 and older.[1] Michigan is the tenth state in the United States, and the first state in the Midwest, to legalize the recreational use of marijuana.[2] The initiative is set to become law by November 26, 2018, according to Secretary of State spokesman Fred Woodhams.[3] Before Michigan residents ‘light up,’ however, caution is advised as marijuana is still an illegal substance under federal law.[4] This advice is particularly true for Black and Latinx people who will likely continue to face higher arrest rates for marijuana than white people after its legalization.[5] As Michigan is the tenth state to legalize marijuana, some lessons can be learned from the experiences of previous states who passed similar legislation. Specifically, data collected from Colorado, Alaska, and Washington, D.C. helps answer the question; what does the passage of Proposal One mean for Michigan and its communities of color?

Latina Lawyers: Underrepresented and Overqualified

By Cleo Hernandez Associate Editor, Volume 23 Editor-in-Chief, Volume 24 In 2009, Justice Sotomayor became the first ever Latina to serve on the United States Supreme Court. Gender violence, sexual harassment, and feminism have all been dancing around on the center stage of world politics lately, as displayed by the traction that the #MeToo movement has gained on both social and mainstream media platforms. And indeed, immense bravery is required of every woman and man that speaks out as a victim of sexual harassment or domestic violence. However, packaging these complex issues into a hashtag, or a sound bite, or a news article has inevitably erased the nuances that define modern day feminism, and that affects women of color. In addition, the current national controversy about immigration has become overtly racialized and criminalized putting certain racial and ethnic groups in the spotlight. These national moods compound to make today a particularly tough time to be a Latina in America. Especially if one is a Latina in a profession with few peers of a similar racial and gender identity. Latinas comprise less than two percent of attorneys in the United States.[1] Even without the recent publicity surrounding these new political conversations, a Latina lawyer faces a career path filled with race, class, and gender-based obstacles.[2] A lack of role models and financial resources can be a barrier for Latinas to even begin to consider attending law school.[3] Once in law school and as an attorney, the lack of Latinas in the profession can feel isolating, and can create low self-esteem in Latinas.[4] There is hardship involved when assimilating and fitting into the law school culture, being tokenized, and being afraid to be labeled as either too passive, or as a “fiery” or “hot-headed” Latina.[5] Furthermore, microaggressions and overt racism can make it difficult to navigate courtrooms and law firms.[6] Latina lawyers report oftentimes being misidentified in the courtroom as the bailiff, the interpreter, the secretary, or the defendant.[7] Additionally, when a Latina lawyer is promoted, she will perceive (or hear directly from others) that her coworkers see her as not qualified for the new position, and believe that she only received the promotion because she was a minority or a woman.[8]

Attacks on Asian Americans

By Ben Cornelius Associate Editor, Volume 23 Kyle Descher was born in Korea, but adopted at a young age by an American couple. [1] Back when he was a college student he and a roommate headed out to a bar after a Washington State University football victory over Oregon. [2] As the pair approached the bar, the remark “fucking Asian” was hurled at Descher. Descher ignored the remark and went about his night.[3] But a few moments later an unknown assailant unleashed a vicious blow that broke Descher’s jaw in two places, and knocked him to the floor, unconscious and bleeding badly.[4] It took three titanium plates to get his jaw back together.[5] His mouth was wired shut.[6] He had to eat through a straw and would wake up several times a night from the throbbing pain.[7] Hate crimes and crimes, and crimes in general, against Asian-Americans have been steadily rising. [8] In Los Angles, an L.A. County Commission on Human Relations report found that crimes targeting Asian-Americans tripled in that county between 2014 and 2015.[9] These sort of attacks also rose in New York City.[10] Between 2008 and 2016, the percentage of Asian and Pacific Islander victims of robbery rose from 11.6 percent to 14.2 percent; felonious assault from 5.2 percent to 6.6 percent; and grand larceny from 10.3 percent to 13.5 percent.[11] The robbery statistic is particularly interesting, as robberies overall were down 29 percent over that same period despite the increase in robberies of Asians.[12] Due to likely underreporting, the statistics may be much more troubling. Language barriers, immigration status, and unfamiliarity with the criminal justice system can cause Asians to be hesitant to report crimes.[13] “They look at us as easier targets,” said Karlin Chan, an activist in New York’s Chinatown.[14] Unfortunately, vicious race-based assaults on Asian-Americans are nothing new.[15] Cases of hate crimes against Asian-Americans can be found all the way back to the 1800’s.[16] The white supremacist group ‘Arsonists of the Order of Caucasians’ savagely murdered four Chinese men whom they blamed for taking away jobs from white workers.[17] The victims were tied up, had kerosene poured on them and then were set ablaze.[18] In 1987, a New Jersey gang calling itself the "Dotbusters" vowed to drive East Indians out of Jersey City by vandalizing Indian-owned businesses.[19] The gang also got violent and used bricks to bludgeon a young South Asian male into a coma.[20] Regardless of how many generations a person may have been here, Asians are often seen as the perpetual foreigner hell-bent on stealing jobs and taking over the country.[21]

Can They Do That? (Part 2): End Sanctuary Cities

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 It is not just the long election cycle that is a defining feature of Michigan politics today, but also the impact of term limits on who seeks what office. The current incumbent is forced out by that constitutional measure, and the candidate to replace him is himself subject to the term limits placed on the state House of Representatives. As part of our continuing series, Can They Do That?, today we examine a signature issue from the campaign of Tom Leonard. Speaker Leonard is currently in charge of Michigan’s lower legislative body.[1] He was first elected to represent the 93rd District in 2012,[2] and as a result is ineligible to run again.[3] In keeping with the “up or out” ethos created by these term limits, Speaker Leonard is seeking the office of Attorney General, citing his previous experience as a Genesee County prosecutor and assistant state attorney general during Mike Cox’s tenure.[4] Public safety is a core part of his new campaign, including a promise to “end sanctuary cities”.[5] So, if elected Michigan Attorney General, can he do that? Well, that depends on a number of factors, not least of which is what Speaker Leonard means by “sanctuary city” and by “end”. The most common definition of “sanctuary city” is a city or municipality that has, by rule or ordinance, limited what local law enforcement can do to assist Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) against those with immigration violations.[6] Even within this definition there can be a lot of variety, with cities such as San Francisco that prohibit cooperation with ICE while using city resources,[7] as well as communities like Chester County, Virginia, that simply refuse to automatically detain suspected immigrants.[8]

The Color of Terrorism

By Rasheed Stewart Associate Editor, Volume 23 Mourners create a memorial in Las Vegas to remember those lost after the 2017 shooting. On October 1, 2017, a 64-year-old white American male opened fire on thousands of concertgoers in Las Vegas, Nevada.[1] Over 58 innocent people were murdered and 546 more were injured, instantly making it the deadliest shooting in modern American history.[2] Under Nevada law, terrorism is defined as, “any act that involves the use or attempted use of sabotage, coercion or violence which is intended to cause great bodily harm or death to the general population.”[3] Seemingly, this senseless act of tragic violence consisted of the exact elements Nevada lawmakers intended to criminalize when they created the statute. Undoubtedly, the facts of the Vegas mass shooting should constitute terrorism under the definition of the Nevada statute; however, national media outlets have been quick to opine their own reasoning for why the single deadliest mass shooting in U.S. modern history should not be considered ‘terrorism.’[4] The myriad of reasons they suggest include the contrariness of the Vegas shooting with Oxford’s definition of ‘terrorism,’ of which requires a political aim.[5] Other explanations focus on the FBI’s definition requiring a political objective.[6] Superficially, the media continues to disseminate implicitly biased conclusions to the general population. In turn, these conclusions excuse significantly violent acts caused by white American males, not Islamic State fighters, and condone them as mass shootings, not terrorism. Why? Doubtless, the answer will not appear in the definition of terrorism; nonetheless, there is an unwritten, implicit understanding that the color of ‘terrorism’ is, and always will be, non-white. To further this conclusion, one must look at other examples of similar incidents, and analyze if this claim holds true. On November 5, 2017, a 26-year-old white American male armed with an assault rifle, shot and killed 26 community members, including a child as young as 18 months while they worshipped inside a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas.[7] No motive had been revealed as the investigation proceeded; however, President Trump, like the various U.S. media outlets that effectively continue to control the narrative, tweeted his reasoning for why this occurred by stating the incident was a, “mental health problem of the highest degree,” and not a “guns situation.” [8] Even after a man intentionally walked into a house of worship, and committed the deadliest mass shooting in Texas history,[9] there was not a single utterance of the word ‘terrorism’ or even an act of ‘terror’ that could be found. Of course, President Trump has conceivably memorized the FBI definition for terrorism and refrained from calling the murderer a terrorist because there was no ‘political aim’ present, right? Wrong.“When They Enter, We All Enter”: Opening the Door to Intersectional Discrimination Claims Based on Race and Disability

This Article explores the intersection of race and disability in the context of employment discrimination, arguing that people of color with disabilities can and should obtain more robust relief for their harms by asserting intersectional discrimination claims. Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw first articulated the intersectionality framework by explaining that Black women can experience a form of discrimination distinct from that experienced by White women or Black men, that is, they may face discrimination as Black women due to the intersection of their race and gender. Likewise, people of color with disabilities can experience discrimination distinct from that felt by people of color without disabilities or by White people with disabilities due to the intersection of their race and disability. Yet often our legal and cultural institutions have been reluctant to acknowledge the intersectional experience, preferring instead to understand people by a singular trait like their race, gender, or disability. While courts have recognized the validity of intersectional discrimination claims, they have offered little guidance on how to articulate and prove the claims, leaving compound and complex forms of discrimination unaddressed. This Article thus offers an analysis of how courts and litigants should evaluate claims of workplace discrimination based on the intersection of race and disability, highlighting in particular the experience of Black disabled individuals. Only by fully embracing intersectionality analysis can we realize the potential of antidiscrimination law to remedy the harms of those most at risk of being denied equal opportunity.