All content categorized with: Criminal Legal System

Filter

Post List

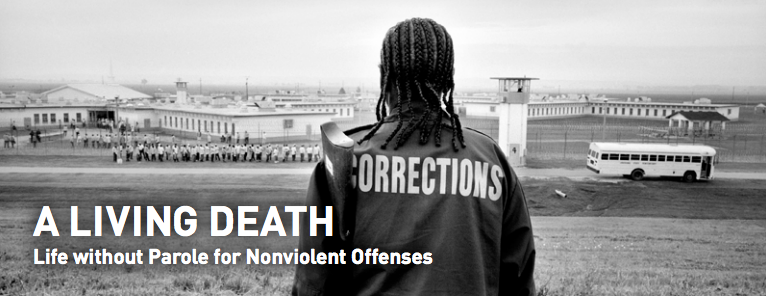

In the News: Life Without Parole

The American Civil Liberties Union just released an “extensive and astonishing report” describing the increasing frequency with which American judges are sentencing nonviolent offenders to life in prison without the possibility of parole. You can visit the ACLU’s interactive site here and read the…COMMENT: The Appearance of Impartiality in New York City’s Stop-and-Frisk Litigation

By Andrew Goddeeris, Associate Editor, Volume 19 This past August, U.S. District Court Judge Shira Scheindlin issued a ruling in Floyd v. City of New York that challenged the New York City Police Department’s (“NYPD”) controversial use of stop-and-frisk practices in the last decade.[1] From January 2004…What the Sentencing Commission Ought to Be Doing Reducing Mass Incarceration

Beginning in the 1970s, the United States embarked on a shift in its penal policies, tripling the percentage of convicted felons sentenced to confinement and doubling the length of their sentences. This shift included a dramatic increase in the prosecution and incarceration of drug offenders. As a result of its move toward long prison sentences, the United States now incarcerates so many people that it has become an outlier; this is not just among developed democracies, but among all nations, including highly punitive states such as Russia and South Africa, and also in comparison to the United States' own long-standing practices. The present rate of incarceration in the United States is currently "almost five times higher than the historical norm prevailing throughout most of the twentieth century." In sum, the United States has a serious over-punishment problem. Our country's imprisonment rate has acquired the name, "mass incarceration," meant to provoke shame about the fact that the world's wealthiest democracy imprisons so many people, even at a time when crime rates have diminished and crime is "not one of the nation's pressing social problems." Most criminal justice scholars agree that our current prison population is too large. They also agree that the impact of imprisonment on the crime rate is modest and that the speed at which people are released from prison bears little relation to the likelihood that they will remain crime free. Many prisoners can serve shorter sentences without triggering an increase in crime. As a result, we can reduce sentence lengths substantially without adversely affecting public safety.Isolated Confinement in Michigan: Mapping the Circles of Hell

For the past twelve months, there has been a burgeoning campaign to abolish, or greatly reduce, the use of segregated confinement in prisons. Advocates for the campaign call such classifications "solitary confinement" despite the fact that in some states, like New York, prisoners in these cells are often double-celled. The Michigan Department of Corrections, as well as other prison systems, uses labels such as "segregation," "special management," "special housing," and "observation" for these classifications. Prisoners ordinarily use traditional terms, such as "the hole." In this Essay we will refer to such restrictive classifications as "segregation" or "segregated confinement." Our perspective on the problems with such classifications comes from serving as counsel for plaintiffs in Hadix v. Caruso. Hadix is a long-running class action regarding what was once called the State Prison of Southern Michigan; in this case, we are attempting to enforce remaining portions of a 1984 consent decree to which the Michigan Department of Corrections (MDOC) is subject. Part of what we describe in this Essay is the harm that segregated confinement has inflicted on mentally ill members of the Hadix class. The evidence of harm to mentally ill prisoners from segregated confinement that we found was entirely predictable. It has long been known that segregated confinement results in the deterioration of the mental health status of many prisoners so confined and the related deterioration of their ability to interact safely with other persons once released from segregation. This Essay, however, will not focus particularly on the harms caused by the propensity of segregated confinement to engender or exacerbate mental illness. We will describe examples drawn from our own experiences and other litigation in Michigan documenting the potential for lethality from assigning medically vulnerable prisoners to segregated confinement - an issue that has received less attention in the national campaign against the use of solitary confinement. We will also suggest explanations for why assigning such prisoners to segregated confinement is so predictably dangerous, as well as why the MDOC has been so slow to recognize these dangers.The Federal Bureau of Prisons: Willfully Ignorant or Maliciously Unlawful?

The Federal Bureau of Prisons ("BOP") and the larger U.S. government either purposely ignore the plight of men with serious mental illness in the federal prison system or maliciously act in violation of the law. I have no way of knowing which it is. In a complex system comprising many individual actors, motivations are most likely complex and contradictory. Either way, uncontrovertibly, the BOP and the U.S. government, against overwhelming evidence to the contrary, continuously assert that there are no men with serious mental illnesses housed in the federal supermax prison, the Administrative Maximum facility in Florence, Colorado, also known as ADX. Men and women with serious mental illnesses may not be constitutionally assigned to supermax confinement. Even BOP's own policies forbid the placement of anyone with a serious mental illness in the ADX. The government claims no one with a serious mental illness is in the ADX. Nonetheless, the place is full of men who by any definition have serious mental illnesses. Any thorough review of the 433 men at the ADX would demonstrate that about one-third of the men suffer a severe mental illness. The prison is filled with men who have been previously found unfit to stand trial, men who have long-standing histories of intensive psychiatric treatment, men who take antipsychotic medication, men who decorate their cells with their own feces, and men who mutilate their own bodies. After an investigation, the Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs and the law firm Arnold & Porter, LLP filed suit on behalf of several individuals and a putative class. The U.S. Department of Justice defends the status quo at the ADX and has moved to dismiss the entire lawsuit for failure to state a claim under the Eighth Amendment. As of this writing, it shows no intention of addressing the systemic failures that have led to so many men with serious mental illnesses being placed at the ADX.The Right to Counsel for Indians Accused of Crime: A Tribal and Congressional Imperative

Native American Indians charged in tribal court criminal proceedings are not entitled to court appointed defense counsel. Under well-settled principles of tribal sovereignty, Indian tribes are not bound by Fifth Amendment due process guarantees or Sixth Amendment right to counsel. Instead, they are bound by the procedural protections established by Congress in the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. Under the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA), Indian defendants have the right to counsel at their own expense. This Article excavates the historical background of the lack of counsel in the tribal court arena and exposes the myriad problems that it presents for Indians and tribal sovereignty. While an Indian has the right to defense counsel in federal criminal court proceedings, he does not in tribal court. This distinction makes a grave difference for access to justice for Americans Indians not only in tribal court, but also in state and federal courts. The Article provides in-depth analysis, background, and context necessary to understand the right to counsel under the ICRA and the U.S. Constitution. Addressing serious civil rights violations that negatively impact individual Indians and a tribe's right to formulate due process, this Article ultimately supports an unqualified right to defense counsel in tribal courts. Defense counsel is an indispensable element of the adversary system without which justice would not "still be done." Tribes, however, were forced to embrace a splintered system of justice that required the adversary system but prohibited an adequate defense. The legacy of colonialism and the imposition of this fractured adversary system has had a devastating impact on the formation of tribal courts. This legacy requires tribal and congressional leaders to rethink the issue of defense counsel to ensure justice and fairness in tribal courts today. The Article concludes that tribes should endeavor to provide counsel to all indigent defendants appearing in tribal courts and calls upon Congress to fund the provision of counsel to reverse the legacy of colonialism and avoid serious human rights abuses.Cascading Constitutional Deprivation: The Right to Appointed Counsel for Mandatorily Detained Immigrants Pending Removal Proceedings

Today, an immigrant green card holder mandatorily detained pending his removal proceedings, without bail and without counsel, due to a minor crime committed perhaps long ago, faces a dire fate. If he contests his case, he may remain incarcerated in substandard conditions for months or years. While incarcerated, he will likely be unable to acquire a lawyer, access family who might assist him, obtain key evidence, or contact witnesses. In these circumstances, he will nearly inevitably lose his deportation case and be banished abroad from work, family, and friends. The immigrant's one chance to escape these cascading events is the off-the-record Joseph hearing challenging detention. If he wins the hearing and is released, he can then secure counsel, and if so, will likely win his case. Yet detained and most likely pro se, he may not even know a Joseph hearing exists, let alone win it, given the complex statutory analysis involved, regarding facts, witnesses, and evidence outside his reach. The immigration detention system today is unique in modern American law, in providing for preventive pretrial detention without counsel pursuant to underlying proceedings without counsel - let alone proceedings so complex that result in a deprivation of liberty as severe as deportation. In this Article, I call this the cascading constitutional deprivation of wrongful detention and deportation. I argue, under modern procedural due process theories, that this cascading constitutional deprivation warrants appointed counsel, notwithstanding traditional plenary power over immigration laws. In a post-Padilla v. Kentucky world where criminal defenders must now advise their clients on the same issues litigated at the Joseph hearing, I argue a right to appointed counsel for mandatorily detained immigrants pending removal proceedings is constitutionally viable and practically feasible.To Plea or Not to Plea: Retroactive Availability of Padilla v. Kentucky to Noncitizen Defendants on State Postconviction Review

The United States incarcerates hundreds of thousands of noncitizen criminal defendants each year. In 2010, there were about 55,000 "criminal aliens" in federal prisons, accounting for approximately 25 percent of all federal prisoners. In 2009, there were about 296,000 noncitizens in state and local jails. Like Jose, these defendants usually do not know that their convictions may make them automatically deportable under the INA. Under the Supreme Court's recent ruling in Padilla v. Kentucky, criminal defense attorneys have an affirmative duty to give specific, accurate advice to noncitizen clients regarding the deportation risk of potential pleas. This rule helps assure that, going forward, noncitizens will be in a position to make informed plea decisions. Knowing the potential consequences of a conviction, they may choose to go to trial, risking a longer sentence but possibly avoiding conviction and subsequent deportation. Unfortunately, for some noncitizen defendants, Padilla was decided too late; at the time Padilla was announced, they had already pleaded guilty, relying upon the advice of defense counsel who failed to advise them of the potential immigration consequences of their conviction. Under what circumstances should relief be available to such noncitizen defendants? This Note argues that courts should apply the rule of Padilla v. Kentucky retroactively on state postconviction review to at least the limited group of defendants whose cases were on direct review when Padilla was decided.A Failure of the Fourth Amendment & Equal Protection’s Promise: How the Equal Protection Clause Can Change Discriminatory Stop and Frisk Policies

Terry v. Ohio changed everything. Before Terry, Fourth Amendment law was settled. The Fourth Amendment had long required that police officers have probable cause in order to conduct Fourth Amendment invasions; to administer a "reasonable" search and seizure, the state needed probable cause. But in 1968, the Warren Court, despite its liberal reputation, lowered the standard police officers had to meet to conduct a certain type of search: the so-called "'stop' and 'frisk.'" A "stop and frisk" occurs when a police officer, believing a suspect is armed and crime is afoot, stops the suspect, conducts an interrogation, and pats him down for weapons. In Terry, the Supreme Court detached reasonableness from probable cause for such "limited" searches and seizures; if a police officer's suspicions, based on articulable facts, lead her to believe that crime is afoot and that a perpetrator is armed, then under the Fourth Amendment, a search for weapons is constitutionally permissible. Despite reversing precedent, Terry and its Supreme Court progeny allowed police officers to rely upon their reasonable suspicions to conduct searches only under narrow conditions. Lower courts, however, have enlarged Terry beyond recognition. Indeed, police officers now have wide latitude to stop and frisk suspects. From the New York stop and frisk numbers flows the class-action Floyd v. City of New York. In Floyd, minority plaintiffs contend that the city's stop and frisk practices unconstitutionally infringe upon personal liberty. The Fourth Amendment as currently interpreted, however, permits cities like New York to promulgate stop and frisk practices that result in racial harassment. What constitutional tool, then, can compel local governments and police departments to revamp their discriminatory stop and frisk techniques? The answer must be the Equal Protection Clause.Systemic Racial Bias and RICO’s Application to Criminal Street and Prison Gangs

This Article presents an empirical study of race and the application of the federal Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) to criminal street and prison gangs. A strong majority (approximately 86%) of the prosecutions in the study involved gangs that were affiliated with one or more racial minority groups. All but one of the prosecuted White-affiliated gangs fell into three categories: international organized crime groups, outlaw motorcycle gangs, and White supremacist prison gangs. Some scholars and practitioners would explain these findings by contending that most criminal street gangs are comprised of racial minorities. This Article challenges and problematizes this factual assumption by critically examining the processes by which the government may come to label certain aiminal groups as gangs for RICO purposes. Based on the study findings, the Article argues that this labeling may be driven by systemic racial biases that marginalize entire racial minority groups and privilege mainstream nonimmigrant White communities. These systemic biases are characterized by converging constructions of race and crime, which fuse perceptions of gang-related crime with images of racial minorities. Conflating racial minorities with criminal activity enables the government to rely upon denigrating racial stereotypes in order to engage in invidious practices of racial profiling and to conduct sweeping arrests of racial minorities under RICO. This conflation also shields groups of nonimmigrant White criminal offenders from being conceptualized as gangs and shields nonimmigrant White neighborhoods from the stigma of having gang problems. In practice, this may harm communities that have White gang problems by preventing the government from executing gang-specific interventions within those communities.