All content categorized with: Criminal Legal System

Filter

Post List

Is Gang Membership a Crime? How RICO Laws Turn Groups into Gangs

By Kerry Martin Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On June 18, 2018, in a courtroom at the Theodore Levin U.S. Courthouse in downtown Detroit, at the end of a long pretrial argument on a matter of evidence, defendant Corey Bailey stood up. The courtroom was nearly full: this was preparation…

California’s Efforts to Reform Bail Leaves Much to be Desired

By Jules Hayer Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Despite recent developments in California to overhaul the bail system, the state still has a long way to go in order to create effective change. In January of this year the California Court of Appeals ruled that, before setting bail, judges must take into account the financial situation of a defendant and determine whether the defendant can be released without imposing a danger to public safety.[1] Moreover, the prosecution bears the burden of presenting clear and convincing evidence which establishes that no conditions of release would ensure the safety of the community, thus requiring the confinement of the person while awaiting trial.[2]From Pelican Bay to Palestine: The Legal Normalization of Force-Feeding Hunger-Strikers

Hunger-strikes present a challenge to state authority and abuse from powerless individuals with limited access to various forms of protest and speech—those in detention. For as long as hunger-strikes have occurred throughout history, governments have force-fed strikers out of a stated obligation to preserve life. Some of the earliest known hunger-strikers, British suffragettes, were force-fed and even died as a result of these invasive procedures during the second half of the 19th century. This Article examines the rationale and necessity behind hunger strikes for imprisoned individuals, the prevailing issues behind force-feeding, the international public response to force-feeding, and the legal normalization of the practice despite public sentiment and condemnation from medical associations. The Article will examine these issues through the lens of two governments that have continued to endorse force-feeding: the United States and Israel. This examination will show that the legal normalization of force-feeding is repressive and runs afoul of international human rights principles and law.Do You See What I See? Problems with Juror Bias in Viewing Body-Camera Video Evidence

In the wake of the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, advocates and activists called for greater oversight and accountability for police. One of the measures called for and adopted in many jurisdictions was the implementation of body cameras in police departments. Many treated this implementation as a sign of change that police officers would be held accountable for the violence they perpetrate. This Note argues that although body-camera footage may be useful as one form of evidence in cases of police violence, lawyers and judges should be extremely careful about how it is presented to the jury. Namely, the jury should be made aware of their own implicit biases and of the limited nature of the footage. Taking a look at the biases that all jurors hold as well as the inherent subjectivity of video footage, this Note shows how implicit biases and the myth of video objectivity can create problems in viewing body-camera footage and the footage should, therefore, be treated carefully when introduced at trial.Batson for Judges, Police Officers & Teachers: Lessons in Democracy From the Jury Box

In our representative democracy we guarantee equal participation for all, but we fall short of this promise in so many domains of our civic life. From the schoolhouse, to the jailhouse, to the courthouse, racial minorities are underrepresented among key public decision-makers, such as judges, police officers, and teachers. This gap between our aspirations for representative democracy and the reality that our judges, police officers, and teachers are often woefully under-representative of the racially diverse communities they serve leaves many citizens of color wanting for the democratic guarantee of equal participation. This critical failure of our democracy threatens to undermine the legitimacy of these important civic institutions. It deepens mistrust between minority communities and the justice system and exacerbates the failures of a public education system already lacking accountability to minority students. But there is hope for rebuilding the trust, accountability and legitimacy of these civic institutions on behalf of minority citizens. There is one place where we have demonstrated a deeper commitment to our guarantee of democratic equality on behalf of minority citizens and exerted greater effort to that end than perhaps in any other domain of our civic life—the jury box. This paper recounts this important history and explores the political theory underlying the equal protection jurisprudence of jury selection. It then applies these lessons gleaned from the jury context to the constitutional defense of efforts to achieve greater racial diversity within the judiciary, law enforcement, and public education, all of which are as important to the legitimacy of our democracy today as the jury has been throughout American history.The Case Against Police Militarization

We usually think there is a difference between the police and the military. Recently, however, the police have become increasingly militarized – a process which is likely to intensify in coming years. Unsurprisingly, many find this process alarming and call for its reversal. However, while most of the objections to police militarization are framed as instrumental arguments, these arguments are unable to capture the core problem with militarization. This Article remedies this shortcoming by developing a novel and principled argument against police militarization. Contrary to arguments that are preoccupied with the consequences of militarization, the real problem with police militarization is not that it brings about more violence or abuse of authority – though that may very well happen – but that it is based on a presumption of the citizen as a threat, while the liberal order is based on precisely the opposite presumption. A presumption of threat, we argue, assumes that citizens, usually from marginalized communities, pose a threat of such caliber that might require the use of extreme violence. This presumption, communicated symbolically through the deployment of militarized police, marks the policed community as an enemy, and thereby excludes it from the body politic. Crucially, the pervasiveness of police militarization has led to its normalization, thus exacerbating its exclusionary effect. Indeed, whereas the domestic deployment of militaries has always been reserved for exceptional times, the process of police militarization has normalized what was once exceptional.Fairness in the Exceptions: Trusting Juries on Matters of Race

Implicit bias research indicates that despite our expressly endorsed values, Americans share a pervasive bias disfavoring Black Americans and favoring White Americans. This bias permeates legislative as well as judicial decision-making, leading to the possibility of verdicts against Black defendants that are tainted with racial bias. The Supreme Court’s 2017 decision in Peña-Rodriguez v. Colorado provides an ex post remedy for blatant racism that impacts jury verdicts, while jury nullification provides an ex ante remedy by empowering jurors to reject convicting Black defendants when to do so would reinforce racially biased laws. Both remedies exist alongside a trend limiting the role of the jury and ultimately indicate that we trust juries to keep racism out of the courtroom in the exceptions to our normal procedures.

Do Indigent and Incarcerated Women Have a Real Right to Reproductive Justice?

By Hira Baig Associate Editor, Volume 23 Reproductive justice is not just concerned with women having access to the healthcare they need, it is also concerned with the disparate impact caused by restrictions on reproductive healthcare. Historically, the more restrictions the Court allows on abortion, the more challenging it becomes for indigent women, women of color, and incarcerated women to get the healthcare they need. In order to achieve reproductive justice, scholars and advocates alike ought to think of a comprehensive way to help all women access the reproductive healthcare they need before, during, and even after pregnancy. Currently, the doctrine surrounding reproductive healthcare, primarily abortion, does not account for women’s social contexts and allows restrictions that keep minority and indigent women from enjoying equal protection of the laws. It comes as no surprise that indigent women face severe restrictions when trying to access abortion. Incarcerated women, however, face even greater hurdles. Today, prisons and jails in the United States confine approximately 206,000 women.[1] Approximately 6-10% of women are already pregnant when they enter a prison or jail.[2] Doctor visits for pregnant women in prison are infrequent, with only 54% of women who reported being pregnant in state prisons receiving pregnancy care.[3]

The End of Mass Incarceration: A Blueprint for Transformative Change

By Rasheed Stewart Associate Editor, Vol. 23 He sued the Philadelphia Police Department over 75 times.[1] As a career civil rights and criminal defense attorney he routinely represented individuals subjected to the oppressive forces of racism pervading law enforcement and the criminal justice system.[2] His nationally acclaimed representation of arrested protestors involved with the “Black Lives Matter” movement solidified his reputation among black and brown people as an authentic, hard-nosed movement lawyer.[3] And now, as Philadelphia’s District Attorney, Larry Krasner has managed to put forth a radical, yet replicable platform for ending mass incarceration. Within three months, Krasner has issued several of the most transformative policies that any prosecutor in U.S. history has dared to even imagine. Rather unsurprisingly, Krasner’s new policies have quickly managed to enrage union leaders of the Philadelphia Fraternal Order of Police,[4] while simultaneously galvanizing influential civil rights activists like Shaun King, in supporting his vision for systemic change.[5] To demonstrate his unrelenting approach to transformative change, Krasner has hit the ground running with a flurry of noteworthy edicts. First, to “broadly reorganize the office’s structure and implement cultural change,” Krasner dismissed 31 members of the office just three days into office, including trial attorneys and several supervisor level staff members.[6] Second, in responding to a judge’s order, Krasner publicly released a secret list of current and former police officers whom prosecutors have sought to keep off the witness stand after a review determined they had a long history of lying, racial bias, or brutality.[7] Moreover, Krasner’s ‘Do Not Call’ list now legitimately sends the foreboding message that cronyism between police officers and ADA’s have no place in an ethically transformed criminal justice system.

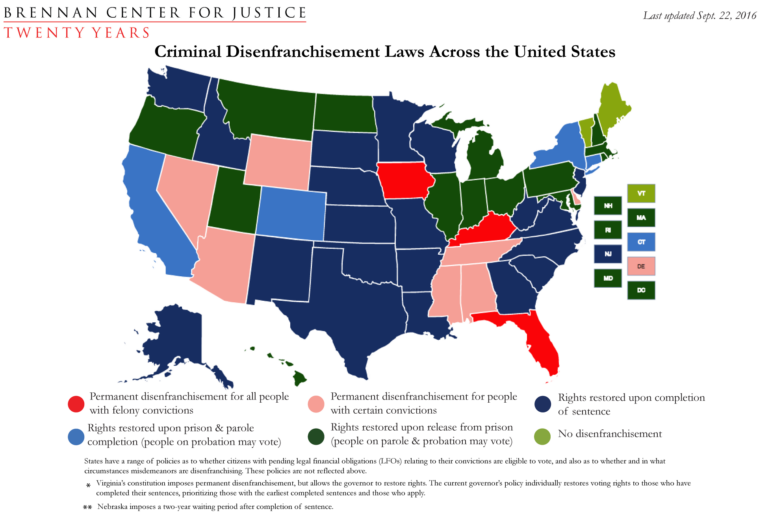

Forever Barred: Examining Felony Disenfranchisement in Florida

By Shanene Frederick Associate Editor, Volume 23 Executive Articles Editor, Volume 24 Desmond Meade was convicted on felony drug and firearm charges back in 2001.[1] Meade, who previously battled drug addiction and experienced homelessness, went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University College of Law.[2] However, his decades-old convictions continue to affect his life today in the form of disenfranchisement. In 2016, Meade could not vote for his wife during her bid for office in the Florida House of Representatives because Florida permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting after they complete their sentences.[3] As the director of Floridians for Fair Democracy, Meade and his team of volunteers have petitioned for over two years in an effort to get a constitutional amendment proposal on Florida’s November 2018 state ballot. [4] Last month, Floridians for Fair Democracy announced that the campaign, Florida Second Chances, had surpassed 799,000 certified signatures, putting it above the required threshold to get on the ballot.[5] If passed, the amendment would restore voting rights to over 1.5 million Floridians, who have been subject to what are arguably the harshest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. [6] The states take various approaches to felony disenfranchisement. As of 2016, all states but Maine and Vermont bar those incarcerated from voting, thirty states restrict those on felony probation from voting, and thirty-four states restrict parolees from voting.[7] Florida is one of twelve states that strip away voting rights post-sentence and post-parole.[8] The effects of Florida’s disenfranchisement scheme are particularly startling: Florida holds 27 percent of the nation’s disenfranchised population, and the total 1.5 million post-sentence disenfranchised individuals make up 48 percent of those who are disenfranchised post-sentence nationally.[9] In 2016, 10.4 percent of Florida’s eligible voting age population was denied the right to vote.[10]