All content tagged with: Voting Rights

Filter

Post List

Carceral Socialization as Voter Suppression

In an era of mass incarceration, many people are socialized through interactions with the carceral state. These interactions are powerful learning experiences, and by design, they are contrary to democratic citizenship. Citizenship is about belonging to a community of equals, being entitled to mutual respect and concern. Criminal punishment deliberately harms, subordinates, and stigmatizes. Encounters with the carceral system are powerful experiences of anti-democratic socialization, and they impact peoples’ sense of citizenship and trust in government. Accordingly, a large body of social science research shows that eligible voters who have carceral contact are significantly less likely to vote or to participate in politics. Hence, the carceral system’s impact on political participation goes well beyond those who are formally disenfranchised due to convictions. It also suppresses participation among the millions of legally eligible voters who have not been formally disenfranchised—people who have had more fleeting encounters with law enforcement or vicarious interactions with the carceral system. This Article considers the implications of these findings from the perspective of voting rights law and the constitutional values underlying it. In a moment when voting rights are under siege, voting rights advocates are in a heated discussion about how our federal and state constitutions protect ideals of democratic citizenship and political equality. This discussion has largely (and for good reason) focused on how the law should address what I call “de jure” suppression: tangible election laws and policies that impose legal barriers to voting, or dilute voting power. Eliminating these formal barriers to voting is vital. But, I argue, fully realizing the constitutional values underlying voting rights will also require also addressing what I call “de facto” suppression, or suppression through socialization. This occurs not through formal legal restrictions on voting, but when state institutions like the carceral system systematically socialize citizens in a manner that is incompatible with democratic citizenship. I show how de facto suppression threatens the constitutional interests protected by the right to vote just like de jure suppression does. In short, by systematically socializing people in a manner that is fundamentally incompatible with democratic citizenship, the state can effectively strip a citizen of much of the instrumental and intrinsic value conferred by the right to vote. Those who are concerned about advancing and protecting voting rights should understand the carceral system’s anti-democratic socialization as a form of political suppression—one that should warrant constitutional scrutiny for the same reasons that de jure suppression should warrant scrutiny.

Power Grab or Not, Expanding Voting Rights is in the Interest of the People, and Democracy

By Mackenzie Walz Associate Editor, Vol. 24 Within days of regaining control of the House of Representatives after an invigorating midterm election, several Democrats vowed to focus their legislative efforts on restoring ethics and transparency in our democratic institutions.[1] As promised, the first bill introduced in the 116th Congress was an ethics reform package titled “For the People.” Also known as HR 1, this act is a sweeping bill aimed at improving three specific aspects of the voting franchise: campaign finance, election security, and voting rights.[2] While Democrats have touted HR 1 as promoting the public interest, Republicans have objected, finding it unnecessary and in furtherance of a partisan agenda.[3] J Christian Adams, president and general counsel of the Public Interest Legal Foundation who served on President Trump’s voter-fraud commission, testified to the House Judiciary Committee that the revisions HR 1 proposes are unnecessary: it has never been easier to vote and it is even difficult to avoid opportunities to register to vote.[4] Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell went even further in his opposition, characterizing the bill as the “Democrat Politician Protection Act.”[5] As one of the most outspoken critics of HR 1, McConnell penned an op-ed for The Washington Post, arguing HR 1 is an “attempt to change the rules of American politics to benefit one party.”[6] While McConnell has taken issue with some provisions more than others, he has continuously expressed that he has no intention of introducing any part of HR 1 in the Senate.[7] Whether or not every provision of HR 1 is necessary or the Act was motivated by partisan interests, studies suggest many provisions of HR 1, individually and collectively, would increase participation among minority voters.[8] There are several structural barriers throughout the political process that impede voter turnout, disproportionately among minority voters: felon disenfranchisement, conducting elections on a Tuesday, arbitrary registration deadlines, and a lack of early voting options. HR 1 seeks to subdue or eliminate these structural barriers, which would increase opportunities for minority participation and, subsequently, increase overall voter turnout.

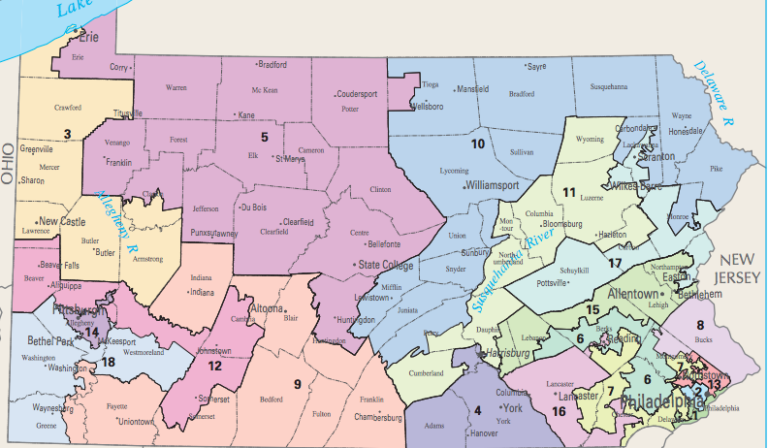

Gerrymandering: Beyond the Partisan Divide

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 Pennsylvania's old Congressional map. Pennsylvania has a long history of a fierce partisan political divisions, due in part to its extremely diverse electorate, geography, and economy.[1] This divide results in massive campaign spending each election cycle and has earned Pennsylvania the label of a battleground or purple state every four years.[2] With this background in mind, it should be no surprise that Pennsylvania is a hub for the practice of gerrymandering which often has a disproportionate effect on communities of color. For partisan gerrymandering, “[t]he playbook is simple: Concentrate as many of your opponents’ votes into a handful of districts as you can, a tactic known as ‘packing.’ Then spread the remainder of those votes thinly across a whole lot of districts, known as ‘cracking.’”[3] Fortunately, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has stepped in, dubbing the Republican created map used over the last six years unconstitutional.[4] In turn, the Court redrew a far more equitable map that may provide a model for nonpartisan redistricting in years to come.[5] The new Congressional map drawn by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in the wake of its recent decision. The new map moves away from the fracturing of communities into disparate districts like the Republican map and attempts to keep counties and municipal areas intact when establishing congressional districts.[6] While the Republican drawn map split 28 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties into separate congressional districts, the new map will only divide 13.[7] An analysis conducted by the Washington Post finds that the new map erases many of the zig-zag lines that were commonplace under the Republican plan, especially in and around urban areas, and eliminates over 1,100 of electoral boarders, a reduction of approximately 37 percent.[8] This focus on compact districts and keeping communities intact when drawing congressional lines is especially notable in Philadelphia, where the new map splits the city into fewer districts.[9] Each of these changes moves towards congressional districts looking “geographically normal,” a goal shared by many nonpartisan experts in the field.[10] Under the new map, districts are defined by strong community ties, unlike the old map where a seafood restaurant held the seventh congressional district “together like a piece of Scotch tape.”[11]

Restoring Democracy in Michigan

By David Bergh Associate Editor, Volume 23 In the wake of the economic destruction wrought by the Great Recession of 2008, many Michigan municipalities fell into dire financial straits.[1] Faced with cities that were sliding into insolvency, the Michigan Legislature passed so-called “emergency manager laws,” in the hope that, by putting the municipality’s finances in the hands of an outside expert, disaster could be averted.[2] Michigan’s existing emergency manager statute was deemed too weak, so the Legislature passed Public Act 4, which was signed by Governor Snyder and went into effect in March 2011.[3] Public Act 4 allowed the State to appoint emergency managers for cities or school districts, and gave them broad power over all financial decisions.[4] This power was then augmented by the passage of Public Act 436, which went into effect in March 2013.[5] Public Act 436, which was given the Orwellian title “Local Financial Stability and Choice Act,” empowered emergency managers to control virtually all aspects of local governance, essentially ending democracy at the local level.[6] Since the first new Emergency Manager Law took effect in 2012, eight cities and three school districts have been brought under state control.[7] The cities brought under state control, which include Detroit, Pontiac, Flint, and Hamtramck, share the common theme of being majority minority.[8] The impact of the Emergency Manager Law on minority communities was so severe, that in 2013 more than half of Michigan’s African American population lived in cities under the control of unelected bureaucrats.[9] Racism has a long history in Michigan - from the KKK nearly getting their candidate elected mayor of Detroit, to the now forgotten 1943 Race Riot during which white mobs, enraged by the presence of black people on Belle Isle, roamed the streets of Detroit unhindered by the police, resulting in the deaths of 24 African Americans.[10] This history is not consigned to the past - cross burnings have occurred in the Detroit area as recently as 2005.[11] Given this history of white supremacy in Michigan, the apparent indifference towards the political rights of black citizens is more than troubling.[12] It is also worth noting that narratives of “financial mismanagement” are false. While local officials deserve some blame for the situation in their cities, the State has been aggressively cutting back on revenue shared with municipalities since 2002.[13] Combined with the impact of the Great Recession, this meant that less affluent communities were simultaneously squeezed by falling tax revenue and declining contributions from the State.[14]Dear Abdul El-Sayed: A Letter to Michigan’s Gubernatorial Candidate

By Hira Baig Associate Editor, Volume 23 Dear Abdul El-Sayed, Life has been challenging for Muslims post 9/11 and has only gotten harder since the 2016 election. Hate crimes against Muslims are on the rise, and my neighborhood mosque now requires police security through the month of Ramadan and every Friday for our jummah prayers. My community is living with a heightened sense of fear since Donald Trump was elected and we are trying to figure out how to combat our country’s violent political landscape. Community conversations often conclude with realizations that we need to use our vote to change these circumstances. We are often left wondering, however, who should we vote for? I write this letter to you and all young Americans running for office because we want to support you; but we need some assurances first. Before I begin, I’d like to thank you. Our country needs you. We need more diverse legislatures on the local, state, and national levels and we appreciate your efforts. I just ask one thing: listen. Listen to the people in this country that need you, and don’t get swept up by power and greed that pervade politics. You don’t need to be bound to people with money and influence. Nearly all of our elected officials have already succumbed to these pressures. We need people like you in public office because it is only after we challenge the very foundation of our political structure will we be able to change public policy for the better. I’d like to share the words of Haney Lopez as you build your platform. Lopez tells us that the middle class is being used to propagate policy decisions that have ultimately hurt most Americans.[1] He writes that politicians use dog-whistles, or coded racial language, to gain white voters, motivating middle-class Americans to elect conservative politicians despite their own interests.[2]

Can They Do That? (Part 1): Shut Down Line 5

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 In the era of the perpetual election cycle, it is no surprise that candidates are already declaring for 2018 races in Michigan. Michigan’s 4-year, off-presidential elections include the state senate, the governor, and the focus of this series, the attorney general. Thus begins our feature, “Can They Do That?,” where we explore the statutory authority of the attorney general’s office as it relates to campaign promises in our diverse state. Dana Nessel announces her bid for Michigan Attorney General in August 2017 Though the attorney general is nominated by their party and not by primary vote, it still helps a candidate to declare early and build a public profile. The first candidate to declare, and the first we will discuss, is Democrat Dana Nessel. Ms. Nessel is an attorney in private practice and former prosecutor whose most notable case was DeBoer v. Snyder[1], later Obergefell v. Hodges[2], the gay-marriage challenge that made it to the Supreme Court and won. At her August 15, 2017 event declaring her candidacy, Ms. Nessel’s speech covered a number of ideas to put in force should she be elected. One of those proposals was “On my first day, I will file to shut down Enbridge Line 5.”[3] So, can she do that? Line 5 is a pipeline that runs under the Straits of Mackinac, the narrowest point between Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsula. Built in 1953,[4] it has worried environmental activists for years and recently attracted a great deal of attention for issues like missing support struts,[5] unprotected pipe surfaces,[6] and the revelation that it was built for weaker currents than exist in the Straits.[7] An oil spill from Line 5 could spread over a vast area.[8] Enbridge also had the worst inland oil spill in U.S. history from a different pipeline in the Kalamazoo River in 2010,[9] raising further concerns about Enbridge’s safety record.Supreme Court Considers Limits of Racial Gerrymandering

By Marcus Baldori Associate Editor, Vol. 22 In the coming months, the Supreme Court is expected to clarify its stance on the legal boundaries of racial gerrymandering. In December 2016 the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections; the case will explore whether a requirement that certain districts have a minimum of 55% Black voting population violates the Equal Protection Clause and the Voting Rights Act.[1] The plaintiffs allege that the 55% floor was a scheme to pack black voters into a few districts, thereby diluting minorities’ overall effect on delegate elections in Virginia.[2] Before the Supreme Court granted cert for this case, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia held[3] that there was no Equal Protection violation because race was a not a predominant factor in the creation of 11 of the 12 challenged state district maps (citing criteria like compactness, contiguity, and incumbency protection[4]). The district court acknowledged that a “racial sorting” violation is independent of intent to dilute minority vote, and focuses only on whether the State has used race as a basis for separating voters.[5] Still, the Court held that the plaintiffs did not make the required showing that the legislature subordinated race-neutral principles to racial considerations in drawing the districts.[6]“Why Should I Go Vote Without Understanding What I Am Going to Vote For?” The Impact of First Generation Voting Barriers on Alaska Natives

This article explores the many forms of discrimination that have persisted in Alaska, the resulting first generation voting barriers faced by Alaska Native voters, and the two contested lawsuits it took to attain a measure of equality for those voters in four regions of Alaska: Nick v. Bethel and Toyukak v. Treadwell. In the end, the court’s decision in Toyukak came down to a comparison of just two pieces of evidence: (1) the Official Election Pamphlet that English-speaking voters received that was often more than 100 pages long; and (2) the single sheet of paper that Alaska Native language speakers received, containing only the date, time, and location of the election, along with a notice that they could request language assistance. Those two pieces of evidence, when set side by side, showed the fundamental unequal access to the ballot. The lessons learned from Nick and Toyukak detailed below are similarly simple: (1) first generation voting barriers still exist in the United States; and (2) Section 203 of the VRA does not permit American Indian and Alaska Native language speaking voters to receive less information than their English-speaking counterparts. The voters in these cases had been entitled to equality for 40 years, but they had to fight for nearly a decade in two federal court cases to get it.Concealed Motives: Rethinking Fourteenth Amendment and Voting Rights Challenges to Felon Disenfranchisement

Felon disenfranchisement provisions are justified by many Americans under the principle that voting is a privilege to be enjoyed only by upstanding citizens. The provisions are intimately tied, however, to the country’s legacy of racism and systemic disenfranchisement and are at odds with the values of American democracy. In virtually every state, felon disenfranchisement provisions affect the poor and communities of color on a grossly disproportionate scale. Yet to date, most challenges to the provisions under the Equal Protection Clause and Voting Rights Act have been unsuccessful, frustrating proponents of re-enfranchisement and the disenfranchised alike. In light of those failures, is felon disenfranchisement here to stay? This Note contemplates that question, beginning with a comprehensive analysis of the history of felon disenfranchisement provisions in America, tracing their roots to the largescale effort to disenfranchise African Americans during Reconstruction, and identifying ways in which the racism of the past reverberates through practices of disenfranchisement in the present day. Applying this knowledge to understandings of prior case law and recent voting rights litigation, a path forward begins to emerge.Deterrence and Democracy: Election Law After Preclearance

By Asma Husain Associate Editor, Vol. 22 In 2013, Chief Justice Roberts delivered the Court’s opinion in Shelby County v. Holder, which struck down key provisions of the Voting Rights Act. Considered the crown jewel of the Civil Rights Movement, the Voting Rights Act had, until that decision, required…