All content tagged with: Indigenous

Filter

Post List

Reviving Indian Country: Expanding Alaska Native Villages’ Tribal Land Bases Through Fee-to-Trust Acquisitions

For the last fifty years, the possibility of fee-to-trust acquisitions in Alaska has been precarious at best. This is largely due to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (ANCSA), which eschewed the traditional reservation system in favor of corporate land ownership and management. Despite its silence on trust acquisitions, ANCSA was and still is cited as the primary prohibition to trust acquisitions in Alaska. Essentially, ANCSA both reduced Indian Country in Alaska and prohibited any opportunities to create it, leaving Alaska Native Villages without the significant territorial jurisdiction afforded to Lower 48 tribes. However, recent policy changes from the Department of Interior reaffirmed the eligibility of trust acquisitions post-ANCSA and a proposed rule from the Bureau of Indian Affairs signals a favorable presumption of approval for Alaska Native fee-to-trust applications. This Note reviews the history and controversy of trust acquisitions in Alaska, and more importantly, it demonstrates the methods in which Alaska Native Villages may still acquire fee land for trust acquisitions after ANCSA.A Framework for Managing Disputes Over Intellectual Property Rights in Traditional Knowledge

Major controversies in moral and political theory concern the rights, if any, Indigenous peoples should have over their traditional knowledge. Many scholars, including me, have tackled these controversies. This Article addresses a highly important practical issue: Can we come up with a solid framework for resolving disputes over actual or proposed intellectual property rights in traditional knowledge? Yes, we can. The framework suggested here starts with a preliminary distinction between control rights and income rights. It then moves to four categories that help to understand disputes: nature of the traditional knowledge under dispute; dynamics between named parties to disputes; unnamed Indigenous claimants; and the various normative systems (for example, custom, U.N. documents, treaties, statutes, administrative regulations) within which disputes are decided. Throughout, examples that inform the framework come principally from Indigenous peoples in the Pacific rim. Lastly the Article tests the framework against some disputes over traditional knowledge in Samoa and New Zealand. This framework is comprehensive and sensitive to context. It is flexible regarding which normative systems are best suited to settling disputes. A test run shows that the framework helps to resolve practical legal issues.Revising the Indian Plenary Power Doctrine

The federal Indian law doctrine of Congressional plenary power is long overdue for an overhaul. Since its troubling nineteenth-century origins in Kagama v. United States (1886), plenary power has justified invasive Congressional interventions and undermined Tribal sovereignty. The doctrine’s legal basis remains a constitutional conundrum. This Article considers the Court’s…

The MMIP Crisis: We Must Not Be Silent[1]

November is Native American Heritage Month (also known as American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month). In honor of this American Indian and Alaska Native Heritage Month, I will be writing about an issue affecting Native communities across the country: the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous peoples (MMIP). This is a crisis “centuries in the making that will take a focused effort and time” to unravel. Recent legislation and policy initiatives to address the crisis mark a turning point in terms of the government’s priority in tackling the crisis.The Enemy is the Knife: Native Americans, Medical Genocide, and the Prohibition of Nonconsensual Sterilizations

This Article describes the legal history of how, twenty years after the sterilizations began, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, in 1978, finally created regulations that prohibited the sterilizations. It tells the heroic story of Connie Redbird Uri, a Native American physician and lawyer, who discovered the secret program of government sterilizations, and created a movement that pressured the government to codify provisions that ended the program. It discusses the shocking revelation by several Tribal Nations that doctors at the IHS hospitals had sterilized at least 25 percent of Native American women of childbearing age around the country. Most of the women were sterilized without their knowledge or without giving valid consent. It explains the obstacles that Connie Redbird Uri and other Native activists faced when confronting the sterilizations, including the widespread acceptance of eugenic sterilizations, federal legislation that gave doctors economic incentives to perform the procedures, and paternalistic views about the reproductive choices of women, and especially women of color. Finally, this Article describes the long-lasting impacts of the federally-sponsored sterilization of Native women. The sterilizations devastated many women, reduced tribal populations, and terminated the bloodlines of some Tribal Nations.

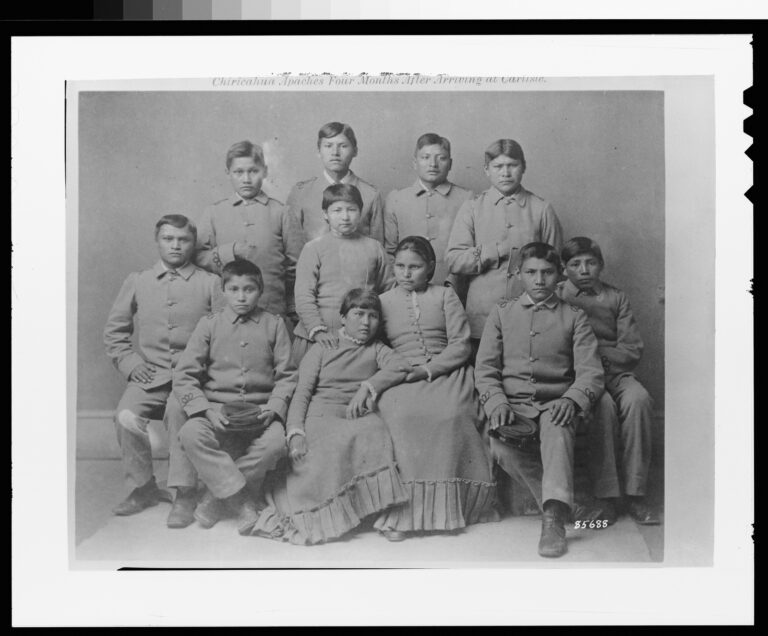

The Dismissed Tragedy Behind the Native American Boarding School System

By: Meghan PateroAssociate Editor, Vol. 26 One thing I’ve realized about myself in law school is that, when reading about historical events, I often downgrade the event’s importance and subsequent consequences. I read the words at face value and dismiss the significance attached to the event at that time. As…Predicting Supreme Court Behavior in Indian Law Cases

This piece builds upon Matthew Fletcher’s call for additional empirical work in Indian law by creating a new dataset of Indian law opinions. The piece takes every Indian law case decided by the Supreme Court from the beginning of the Warren Court until the end of the 2019-2020 term. The scholarship first produces an Indian law scorecard that measures how often each Justice voted for the “pro- Indian” outcome. It then compares those results to the Justice’s political ideology to suggest that while there is a general trend that a more “liberal” Justice is more likely to favor the pro-Indian interest, that trend is generally weak with considerable variance from Justice to Justice. Finally, the article then creates a logistic regression model in order to try to predict whether a pro-Indian outcome is likely to prevail at the Court. It finds six potential variables to be statistically significant. It uses quantitative analysis to prove that the Indian interest is more likely to prevail when the Tribe is the appellant, when the issue is framed as a jurisdictional contest, and when the case arises from certain regions of the country. It suggests that Indian law advocates may use these insights to help influence litigation strategies in the future.Textualism’s Gaze

This Article attempts to address why textualism distorts the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence in Indian law. I start with describing textualism in federal public law. I focus on textualism as described by Justice Scalia, as well as Scalia’s justification for textualism and discussion about the role of the judiciary in interpreting texts. The Court is often subject to challenges to its legitimacy rooted in its role as legal interpreter that textualism is designed to combat.Under Coyote’s Mask: Environmental Law, Indigenous Identity, and #NoDAPL

This Article studies the relationship between the three main lawsuits filed by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, and the Yankton Sioux Tribe against the Dakota Access Pipeline (DaPL) and the mass protests launched from the Sacred Stone and Oceti Sakowin protest camps. The use of environmental law as the primary legal mechanism to challenge the construction of the pipeline distorted the indigenous demand for justice as U.S. federal law is incapable of seeing the full depth of the indigenous worldview supporting their challenge. Indigenous activists constantly re-centered the direct actions and protests within indigenous culture to remind non-indigenous activists and the wider media audience that the protests were an indigenous protest, rather than a purely environmental protest, a distinction that was obscured as the litigation progressed. The NoDAPL protests, the litigation to prevent the completion and later operation of the pipeline, and the social movement that the protests engendered, were an explosive expression of indigenous resistance—resistance to systems that silence and ignore indigenous voices while attempting to extract resources from their lands and communities. As a case study, the protests demonstrate how the use of litigation, while often critical to achieving the goals of political protest, distorts the expression of politics not already recognized within the legal discourse.

The Indian Child Welfare Act on Appeal: Is It a Racial or Political Preference?

By Taylor Jones Associate Editor, Vol. 24 On October 4, 2018, the Northern Federal District Court of Texas held the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) to be unconstitutional. Since that decision, Cherokee Nation, Navajo Nation, and other tribes are seeking to have the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals overturn the decision. Enacted as a response to abhorrent mistreatment and racism against Native children and families in the foster care and child welfare system, ICWA is a critical act that protects the best interests of Native children. In the absence of ICWA Native people are left vulnerable to the previous maltreatment and abuses at the hands of state governments. Throughout American history Native American people have been abused and mistreated by the federal and state governments. ICWA was enacted in 1978 as a response to a crisis that Native people have endured for centuries: Native children being separated from their families and tribes by state child welfare and private adoption agencies. Around the time of enactment it was estimated that 25-35% of Native children were being removed from their families, and of those children removed approximately 85% were placed outside of their communities regardless of whether there were fit and willing relatives within the community available for placement.[1] This process has been recognized as the result of racist and culturally insensitive beliefs that Native children would live better, more productive lives in the homes of white, middle-class families.[2]