By Shanene Frederick

Associate Editor, Volume 23

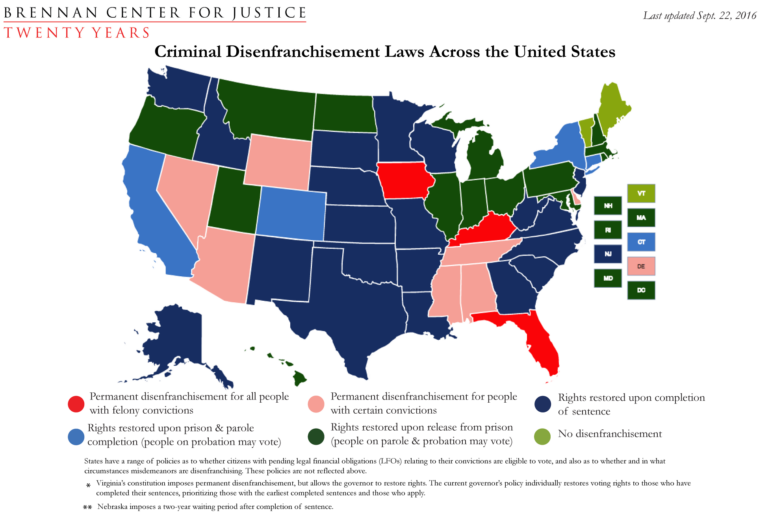

Executive Articles Editor, Volume 24 Desmond Meade was convicted on felony drug and firearm charges back in 2001.[1] Meade, who previously battled drug addiction and experienced homelessness, went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University College of Law.[2] However, his decades-old convictions continue to affect his life today in the form of disenfranchisement. In 2016, Meade could not vote for his wife during her bid for office in the Florida House of Representatives because Florida permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting after they complete their sentences.[3] As the director of Floridians for Fair Democracy, Meade and his team of volunteers have petitioned for over two years in an effort to get a constitutional amendment proposal on Florida’s November 2018 state ballot. [4] Last month, Floridians for Fair Democracy announced that the campaign, Florida Second Chances, had surpassed 799,000 certified signatures, putting it above the required threshold to get on the ballot.[5] If passed, the amendment would restore voting rights to over 1.5 million Floridians, who have been subject to what are arguably the harshest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. [6] The states take various approaches to felony disenfranchisement. As of 2016, all states but Maine and Vermont bar those incarcerated from voting, thirty states restrict those on felony probation from voting, and thirty-four states restrict parolees from voting.[7] Florida is one of twelve states that strip away voting rights post-sentence and post-parole.[8] The effects of Florida’s disenfranchisement scheme are particularly startling: Florida holds 27 percent of the nation’s disenfranchised population, and the total 1.5 million post-sentence disenfranchised individuals make up 48 percent of those who are disenfranchised post-sentence nationally.[9] In 2016, 10.4 percent of Florida’s eligible voting age population was denied the right to vote.[10]