Internal Scholarship

Filter

Post List

With a Side of Higher Mortality: Prison Food in the United States

By Cleo Hernandez Associate Editor, Volume 23 November begins a holiday season in the United States that is stuffed full of increased attention on food. The average American does seem to gain just under one pound of body weight during the holiday season.[1] However, some individuals avoid this holiday gluttony through no choice of their own.[2] Prisoners in the United States on a day-to-day basis have an extremely different interaction with the “food” they are provided. Research about the nature of prison food in the United States is sparse, but there seems to be a general consensus that an inmate does not receive adequate food.[3] The United States Supreme Court has recognized that the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment in the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution imposes duties on prison officials to provide prisoners with adequate food.[4] In reality many prisoners encounter food that is primarily a product of state legislative choices about funding, and thus prison meal systems will vary widely from state to state and from prison to prison.[5] This means that in some states prisoners are simply not fed enough. In Gordon County, Georgia prisoners only get two meals per day, served at least 10 hours apart.[6] In Butte-Silver Bow County, Montana, prisoner meals averaged between 1,700 and 2,000 calories per day.[7] Furthermore, the nutritional value of the meals seems to be low, with items like margarine, brownies, and cake tacked on to meager meals in order to reach calorie minimums.[8] Certainly, prisoners are not getting the diet rich in a diverse array of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables recommended by United States Department of Agriculture.[9]

Can They Do That? (Part 1): Shut Down Line 5

By John Spangler Associate Editor, Volume 23 In the era of the perpetual election cycle, it is no surprise that candidates are already declaring for 2018 races in Michigan. Michigan’s 4-year, off-presidential elections include the state senate, the governor, and the focus of this series, the attorney general. Thus begins our feature, “Can They Do That?,” where we explore the statutory authority of the attorney general’s office as it relates to campaign promises in our diverse state. Dana Nessel announces her bid for Michigan Attorney General in August 2017 Though the attorney general is nominated by their party and not by primary vote, it still helps a candidate to declare early and build a public profile. The first candidate to declare, and the first we will discuss, is Democrat Dana Nessel. Ms. Nessel is an attorney in private practice and former prosecutor whose most notable case was DeBoer v. Snyder[1], later Obergefell v. Hodges[2], the gay-marriage challenge that made it to the Supreme Court and won. At her August 15, 2017 event declaring her candidacy, Ms. Nessel’s speech covered a number of ideas to put in force should she be elected. One of those proposals was “On my first day, I will file to shut down Enbridge Line 5.”[3] So, can she do that? Line 5 is a pipeline that runs under the Straits of Mackinac, the narrowest point between Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsula. Built in 1953,[4] it has worried environmental activists for years and recently attracted a great deal of attention for issues like missing support struts,[5] unprotected pipe surfaces,[6] and the revelation that it was built for weaker currents than exist in the Straits.[7] An oil spill from Line 5 could spread over a vast area.[8] Enbridge also had the worst inland oil spill in U.S. history from a different pipeline in the Kalamazoo River in 2010,[9] raising further concerns about Enbridge’s safety record.UPCOMING EVENT 11/14: The Path to Equitable Revitalization in Detroit

The Michigan Journal of Race & Law presents The Path to Equitable Revitalization in Detroit: A Discussion with Professor Alicia Alvarez Please join us for a discussion with Professor…

The School to Prison Pipeline Comes to Pre-K

By Elliott Gluck Associate Editor, Volume 23 For years, the startling rates of suspensions and expulsions in America’s public schools have raised concerns for stakeholders across the educational landscape.[1] These disciplinary actions are frequently connected with higher drop-out rates, lower lifetime earnings, and higher rates of incarceration.[2] With African American students facing expulsion and suspension at over three times the rate of their non-Hispanic white peers and American Indian students overrepresented in exclusionary discipline by six times their overall school enrollment, a clear pattern of racial disparity emerges in the current approach to school discipline.[3] Startlingly, in the last few years, research has shown these disparities in school discipline are not confined to K-12, but extend to preschools as well.[4] The first major study exploring suspensions and expulsions in preschools came from Walter S. Gilliam and Golan Shahar in 2006.[5] Their Massachusetts study showed that preschool expulsions occurred at over 34 times the rate of K-12 expulsions and were influenced by larger class sizes, younger enrollees, and elevated “teacher job stress.”[6] While Massachusetts had a relatively low K-12 expulsion rate, these preschool expulsions still occurred at more than 13 times the national K-12 average.[7] Gilliam and Shahar noted that while all states have legal requirements for school attendance starting between ages five and eight, no such law exists for pre-K programs.[8] The authors suggest that, “these laws may reduce expulsion during the K-12 years, because the expulsion would create a legal problem for the parents who would then need to find educational programming for children elsewhere.”[9]

Resist, Revolt, Rinse, Repeat

By Cleo Hernandez Associate Editor, Volume 23 A public square, angry words, angry people, police in riot gear, torches bright against a night sky, flags, homemade signs and banners, summer heat. Some would say that this is what democracy looks like, [1] but perhaps it is the failure of democracy that brings people to the streets. For those whose combined voices, votes, or dollars are too small in number to form a majority capable of effecting political change,[2] or for those of color competing against a white majority, protests and other forms of unconventional political participation may seem more effective at achieving equality goals.[3] The recent incidents in Charlottesville can be characterized as a racial protest.[4] Charlottesville 2017[5] was not a spontaneous outburst of hatred and violence fanned into flame by diverging partisan reactions to the Trump administration,[6] but another battle in America’s longstanding struggle against racism. Early protest scholarship orbited around the assumption that the benefits of protest are undeniable, but that the extreme inherent costs should always prevent people from protesting.[7] Costs of protesting can include anything from the increased likelihood of arrest, to the time required to protest, to the possibility of losing employment because of protest participation. Indeed, the law operates on four different yet interlocked levels to restrict protest and discourage people from protesting.[8] Police officers regulate protestor behavior in the streets with varying degrees of physical force.[9] Legislatures enact laws that restrict protests in time, place, and manner.[10] Administrative agencies sometimes require permits and fees for protests.[11] And finally, the judiciary then operates as a reviewer of these three regulators in freedom of speech concerns, and as a final restrictor for protestors if they face criminal charges.[12]

American Indian Political Representation: An Update on Congressional Races Across America

By Ben Cornelius Associate Editor, Volume 23 The highest achieving American Indian in U.S. politics was Kaw-Osage-Pottawatomie Charles Curtis. Curtis was the 31st Vice President of the United States serving with President Herbert Hoover.[1] Curtis started his career as a horse jockey, later attending law school, leading to his election to Congress. He eventually became a prominent member of the Republican party and was chosen as Hoover’s Vice-President.[2] Of the current 535 members of Congress, only two are members of federally recognized American Indian tribes. Tom Cole of the Chickasaw Nation is currently serving his 8th term as a Republican U.S. Representative for Oklahoma’s 4th District.[3] “Cole is an advocate for a strong national defense, a tireless advocate for taxpayers and small businesses and a leader on issues dealing with Native Americans and tribal governments.”[4] The other Ameircan Indian Congressman is Representative Markwayne Mullin, a Cherokee Republican representing Oklahoma’s 2nd Congressional District. Mullin is a businessman and a former professional Mixed Martial Arts fighter with a 3-0 record.[5] Given the dire circumstances on many reservations, increased Native American political representation is vital for the future of Indian Country. American Indians have a 28.3% poverty rate, compared to 15.5% for the nation as whole.[6] Lack of access to quality health care has led to huge disparities in health, for example the post neonatal death rate is over twice that of the U.S. white rate, 4.8 deaths per 1000 live births versus 2.2.[7] Education is another roadblock, as only 67% of American Indian students graduate from high school, compared to the national average of 80%.[8] Indian issues typically receive little attention in mainstream political dialogue. If there is any attention, it usually involves hostility to Tribal business ventures,[9] business that are vital to many tribes ability to support themselves and provide for tribal members.

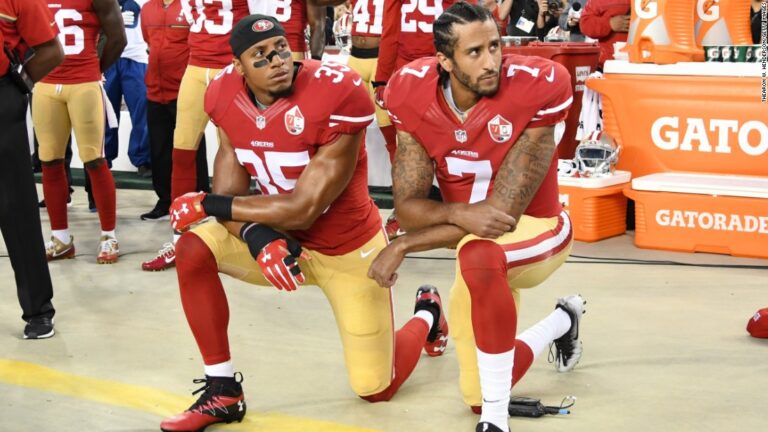

UPCOMING EVENT 10/11: Clear Eyes, Full Hearts, Linked Arms: A Panel on the NFL Protests

Is Colin Kaepernick the first to use sports as a platform for protest? How is the First Amendment shaping the debate? Does labor law provide protections for athletes who protest? Join Professors Kate Andrias, Sherman Clark and Len Niehoff as they discuss these and other key legal issues surrounding the…

Registration is now open for MJR&L’s 2018 Symposium: A More Human Dwelling Place: Reimagining the Racialized Architecture of America

Presented by the Michigan Journal of Race & Law, “A More Human Dwelling Place: Reimagining the Racialized Architecture of America” is a symposium happening on February 16 and 17 at the University of Michigan Law School. Over two days, we will examine five archetypal spaces in America: homes and neighborhoods, schools,…Introducing the Volume 23 Associate Editors

Congratulations to the Volume 23 Associate Editors! The Michigan Journal of Race & Law is beyond excited to have you join our family. Please give a warm welcome to: Hira Baig David Bergh Morgan Birck Ben Cornelius Shanene Frederick Elliott Gluck Gloria…Rethinking Death Penalty Reform: The Case Against Death-qualified Juries

By Anonymous Associate Editor Since the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated the death penalty through Gregg in 1976, racial bias has continued to pervade its administration.[1] 34.5% of defendants executed have been Black and 55.6% have been white,[2] despite the fact that only 13.3% of people in the U.S. identify as Black, while 77.1% identify as white.[3] I consider myself an abolitionist regarding the death penalty, as I do not think that it is justified for the state to kill a citizen in any circumstance. However, given these alarming statistics and the dire situation they illuminate, I find that efforts to reform the capital process to reduce racial disparity are also worthwhile. Reformers would do well to focus on the elimination of the death qualification process, as well as Eighth Amendment and Batson challenges to the death penalty.