Abolition Economics

Over the past several decades, Law & Economics has established itself as one of the most well-known branches of interdisciplinary legal scholarship. The tools of L&E have been applied to a wide range of legal issues and have even been brought to bear on Critical Race Theory in an attempt to address some of CRT’s perceived shortcomings. This Article seeks to reverse this dynamic of influence by applying CRT and related critical perspectives to the field of economics. We call our approach Abolition Economics. By embracing the abolitionist ethos of “dismantle, change, and build,” we seek to break strict disciplinary habits of modelling and identification, destabilize value systems implicit in mainstream economics, model society more fully as made up of interconnected humans, and develop a richer and more realistic understanding of racialized economic inequality, hierarchy, and oppression. We argue that, contrary to accepted disciplinary conventions, such an endeavor does not introduce new (inappropriate) ideological content into (objective) economics; rather, this endeavor is necessary to fully reveal the ideological content already embedded in mainstream economics as it is currently practiced, and the consequences of that embedding in supporting the functioning of systems of racial capitalism and racial injustice. We believe that imagining the possibility of a different economics—an Abolition Economics—can be an act not only of resistance but, crucially, of freedom-making.

Introduction

The influence of economic analysis on legal scholarship is longstanding, widespread, and well-known.1See generally Richard A. Epstein, Law and Economics: Its Glorious Past and Cloudy Future, 64 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1167 (1997) (recounting the history and growth of law and economics as an intellectual movement). Indeed, in the ninth iteration of a treatise that he first published more than fifty years ago, Richard Posner asserts that “[e]conomic analysis of law is the foremost interdisciplinary field of legal studies,” as demonstrated “by the number of journals devoted to the field, by the amount of encyclopedic coverage of it, and by the number of books . . . blanketing the field.”2 Richard A. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law xxi (9th ed. 2014). One of the reputed virtues of the Law & Economics (L&E) movement that has helped to build its influence is its purportedly neutral and scientific methodology.3See, e.g., Mark V. Tushnet, Law, Science, and Law and Economics, 21 Harv. J.L. Pub. Pol’y 47 (1997); Morton J. Horwitz, Law and Economics: Science or Politics?, 8 Hofstra L. Rev. 905, 911 (1980). For example, economic analysis of law often focuses on the concept of efficiency—“an objective and scientific concept, [which] inoculat[es] L&E adherents against the tendency to substitute personal normative priors for cold-blooded logic.”4Neil H. Buchanan & Michael C. Dorf, A Tale of Two Formalisms: How Law and Economics Mirrors Originalism and Textualism, 106 Cornell L. Rev. 591, 599 (2021).

To be sure, L&E’s methodologies and claims of objectivity have long been subject to trenchant criticism.5See Anita Bernstein, Whatever Happened to Law and Economics?, 64 Md. L. Rev. 303, 303-04 (2005) (citing and summarizing critiques). Commentators have described L&E’s focus on efficiency as “incoherent,”6Duncan Kennedy, Cost-Benefit Analysis of Entitlement Problems: A Critique, 33 Stan. L. Rev. 387, 388 (1981). lamented that the movement is “sick and spreads sickness,”7Leonard R. Jaffee, The Troubles with Law and Economics, 20 Hofstra L. Rev. 777, 779 (1992). and argued that its supposedly objective approach is actually inherently subjective, “permit[ting] conservative jurists to make all-things-considered and ideologically laden value choices and then use L&E . . . to offer post hoc rationalizations for those choices.”8Buchanan & Dorf, supra note 4, at 596. Criticisms such as these have often been accompanied by declarations or predictions of L&E’s demise.9See Bernstein, supra note 5, at 303-04. Yet despite the frequency and forcefulness of critiques against L&E and neoliberal economics more broadly, the influence of economic analysis on law has endured.10See Buchanan & Dorf, supra note 4, at 602 (“[T]his particular orthodoxy has the remarkable ability to come out on the short end of virtually all such debates but somehow never to ‘lose’ in the sense of being jettisoned due to its flaws.”). L&E continues to be applied to a broad range of legal issues,11See Posner, supra note 2, at xxii (explaining that his book applies economic analysis to “almost the entire legal system”). including areas in which its assumptions and methods might seem to be incongruously out of place. As a striking illustration, L&E has even been brought to bear on Critical Race Theory (CRT) in an effort to “cure some of the deficiencies” in CRT’s approach to analyzing racial diversity in the workplace.12Devon W. Carbado & Mitu Gulati, The Law and Economics of Critical Race Theory, 112 Yale L.J. 1757, 1761 (2003). This is not to suggest that Carbado and Gulati are dismissive of the value and insights of CRT. To the contrary, the authors also apply CRT to address deficiencies in L&E, and use their analysis of workplace diversity to demonstrate the collaborative potential of the two schools of thought. See id. at 1761-62.

This Article seeks to destabilize and reverse this dynamic of influence in several ways. Specifically, just as the tools of neoliberal economics have been applied to give rise to a distinctive approach to legal analysis, we endeavor to apply the tools of CRT and related Critical perspectives to give rise to a distinctive approach to economic analysis. We call this approach Abolition Economics. Our approach is abolitionist in at least two senses. First, it seeks to apply the abolitionist ethos of “dismantle, change, and build”13See Critical Resistance, How We Organize, https://criticalresistance.org/how-we-organize/. to the discipline of economics itself. Rather than applying ostensibly “objective” methods, we employ unabashedly critical insights from CRT, stratification economics, and feminist economics to break strict disciplinary habits of modelling and identification, destabilize value systems implicit in economic analysis, and develop a more realistic understanding of racialized economic inequality and hierarchy. Second, our approach applies this rebuilt understanding to expose the role that mainstream economics plays in legitimizing and perpetuating racial capitalism, racial injustice, and interwoven systems of power and oppression. Exposing those contributions and exploring ways in which a rebuilt understanding of economics can combat them is an incremental but important step in the long-term abolitionist movement.

We pursue these goals in the following way. Part I begins by defining key terms such as “abolition” and “economics” as used in this Article, and by providing an overview of what the practice of Abolition Economics might look like. Part II turns to the process of revealing and dismantling the assumptions and methods of mainstream neoliberal economics. This Part pays particular attention to what we term the Mathematical Industrial Complex, or the use of mathematics and statistics to create, invisibilize, and distort “facts” about economic problems, and to devalue and dehumanize people and their communities. Part III takes up the challenge of changing and building. This Part focuses on the importance of listening, seeing, and imagining—listening to the narratives of lived experience, seeing the realities of racism and racial capitalism, and imagining a radically different and more humane approach to economic analysis. Finally, the Article concludes with some tentative observations about the prospects of Abolition Economics as an intellectual movement and its relationship to the broader abolitionist struggle.

I. Definitions and Practices

The scholar-activist Ibram X. Kendi, an architect of antiracist theorizing and practice, begins his How To Be an Antiracist with definitions. He does this because “[d]efinitions anchor us in principles.”14 Ibram X. Kendi, How To Be an Antiracist 17 (2019). In laying out a vision for an Abolition Economics, we believe it is crucial that we follow this same discipline, that we be “tangible and exacting”15Id. at 18. in how we use words to say precisely what we mean. These definitions will in turn contribute to the “radical reorientation of our consciousness”16Id. at 23. that is an essential part of abolition movements.

A. Abolition

The first term to define is abolition itself. As Dorothy Roberts has observed, activists have resisted adopting a rigid understanding of abolition and have instead used the term to capture a range of goals and ideals.17See Dorothy E. Roberts, Abolition Constitutionalism, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 1, 6 (2019). One such goal that has received particular emphasis in recent years is prison abolition—i.e., “the movement to abolish the prison industrial complex . . . [which] functions to oppress black people and other politically marginalized groups in order to maintain a racial capitalist regime.”18Id. at 7. For other recent examples of prison abolition scholarship, see Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Abolition Geography: Essays Toward Liberation (Brenna Bhandar & Albert Toscano eds.2022); René Reyes, Abolition Constitutionalism and Non-Reformist Reform: The Case for Ending Pretrial Detention, 53 Conn. L. Rev. 667 (2021); Allegra M. McLeod, Envisioning Abolition Democracy, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 1613 (2019); Dylan Rodríguez, Abolition as Praxis of Human Being: A Foreword, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 1575 (2019); Allegra M. McLeod, Prison Abolition and Grounded Justice, 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1156 (2015). But abolition undoubtedly encompasses broader goals as well. Ruth Wilson Gilmore emphasizes that “[a]bolition is a movement to end systemic violence, including the interpersonal vulnerabilities and displacements that keep the system going. In other words, the goal is to change how we interact with each other and the planet by putting people before profits, welfare before warfare, and life over death.”19 Gilmore, supra note 18, at 20. Perhaps more lyrically, Dylan Rodríguez describes abolition as “a practice, an analytical method, a present-tense visioning, an infrastructure in the making, a creative project, a performance, a counterwar, an ideological struggle, a pedagogy and curriculum, an alleged impossibility that is furtively present.”20Rodríguez, supra note 18, at 1578. See also Roberts, supra note 17, at 6-7 (quoting Rodríguez’s account of abolition and observing that he describes it “lyrically”). These broader conceptions include efforts to abolish “a wide range of systems, institutions, and practices beyond criminal punishment (such as the wage system, animal and earth exploitation, and racialized, gendered, and sexualized violence) and forms of oppression beyond white supremacy (such as patriarchy, capitalism, heteronormativity, ableism, colonialism, imperialism, and militarism).”21Roberts, supra note 17, at 7 (quoting Manifesto for Abolition, Abolition Journal, https://abolitionjournal.org/frontpage) (internal quotations and citations omitted).

Importantly, abolition in all of these forms is as much a positive endeavor of creation as it is a negative endeavor of destruction. For instance, Professor Roberts stresses that in the context of prison abolition, “eliminating current carceral practices must occur alongside creating a radically different society that has no need for them,”22Id. at 43. and calls on us to “imagine and build a more humane and democratic society that no longer relies on caging people to meet human needs and solve social problems.”23Id. at 7-8. Professor Gilmore similarly maintains that “[a]bolition is about presence, not absence. It’s about building life-affirming institutions.”24 Angela Y. Davis, Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, & Beth E. Richie, Abolition. Feminism. Now. 51 (2022) (quoting Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Making and Unmaking Mass Incarceration Conference, Keynote Address at the University of Mississippi (Dec. 2019). The abolitionist organization Critical Resistance embraces these constructive ideals in its “theory of change” framework that seeks to dismantle, change, and build.25 Critical Resistance, supra note 13. It is a vision that includes “build[ing] models today that can represent how we want to live in the future. It means developing practical strategies for taking small steps that move us toward making our dreams real and that lead us all to believe that things really could be different.”26 . Critical Resistance, What is the PIC? What is Abolition?, https://criticalresistance.org/mission-vision/not-so-common-language/.

Thus, as used in this Article, abolition means a process of dismantling, changing, and building understandings of economics with a goal of abolishing systems of oppression, exploitation, and white supremacy with which mainstream economics is intertwined. However, before the process of destruction and reconstruction can commence, we must start with revelation. This is the stage of abolition to which we now turn: revealing economics as an intertwined ideology of neoliberalism, capitalism, globalism, and racism. We will once again begin with definitions.

B. Economics

In defining economics, we start with the definition offered by the American Economic Association (AEA), a self-described “non-profit, non-partisan, scholarly association dedicated to the discussion and publication of economics research.”27 American Economic Association, About the AEA, https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea. The AEA explains:

Economics can be defined in a few different ways. It’s the study of scarcity, the study of how people use resources and respond to incentives, or the study of decision-making. It often involves topics like wealth and finance, but it’s not all about money. Economics is a broad discipline that helps us understand historical trends, interpret today’s headlines, and make predictions about the coming years.28 American Economic Association, What is Economics?, https://www.aeaweb.org/resources/students/what-is-economics.

This definition is very much in keeping with L&E’s claims to neutrality, objectivity and methodological rigor.29See Horwitz, supra note 3, at 905; Buchanan & Dorf, supra note 4 at 600. But self-definitions can often be self-serving, and can obscure as much as they reveal. Moreover, the act of definition can be a central part of domination.30See, e.g., Kendi, supra note 14; Cheryl I. Harris, Whiteness as Property, 106 Harv. L. Rev. 1707 (1993); White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology 2 (Tukufu Zuberi & Eduardo Bonilla-Silva eds., 2008). It is therefore vital to probe more deeply into just what “economics” means as understood and utilized by its modern neoliberal adherents.

The importance of unpacking conventional definitions in this way has been powerfully demonstrated by Cheryl Harris. In Whiteness as Property,31Harris, supra note 30. her classic article that helped shaped the CRT movement,32See Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement (Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller & Kendall Thomas eds., 1996). Professor Harris explains how the law defines key terms and concepts in ways that enshrine white power and privilege:

The law expresses the dominant conception of “rights,” “equality,” “property,” “neutrality,” and “power”: rights mean shields from interference; equality means formal equality; property means the settled expectations that are to be protected; neutrality means the existing distribution, which is natural; and, power is the mechanism for guarding all of this.33 Harris, supra note 30, at 1778.

These definitions serve and protect whiteness as a property interest—the core characteristic of which is “the legal legitimation of expectations of power and control that enshrine the status quo as a neutral baseline, while masking the maintenance of white privilege and domination.”34Id. at 1715. Harris thus illustrates that definition is the skeleton, the foundation, on which racial inequality and racial exploitation rely. This process of imposing ostensibly neutral but functionally racist definitions, coupled with the simultaneous disavowal that anything unneutral or racist is actually happening at all, is crucial to maintaining a system that claims to be about possibility and freedom but is, in reality, about constraint and unfreedom. And all of the concepts that Harris identifies—rights, equality, property, neutrality, power—are not only central to law, but also to economics.

Thus, exposing and analyzing the way in which economics has defined these terms is central to the project of dismantling the neoliberal ideology that lies beneath the purportedly neutral science of economics. For just as CRT insists that the law is never neutral, Abolition Economics will insist that economics is never neutral, and that the existing distribution of resources and opportunities is planned, purposeful, and jealously guarded. And just as prison abolitionists aspire “to denaturalize the carceral state,”35 Davis et al., supra note 24, at 8. we will aspire to denaturalize the assumptions and methods of neoliberal economics. We pursue these goals by highlighting the central role of economics in the ideological project that maintains systems of power and oppression, including the prison industrial complex, capitalism, and social hierarchy. Doing so requires a closer look at historical definitions of economics as a discipline.

1. Historical Definitions

Economics is a social science. On that, economists would generally agree, even if what it means to be both social and science is somewhat perplexing. Beyond that, definitions may diverge, and they have certainly evolved over time. At the beginning of his book What’s Wrong with Economics?, Robert Skidelsky presents a series of definitions that also effectively summarizes the historical development of the field:

Historically, there are two main definitions of the subject. The first makes it the study of wealth; the second the study of choice. The first dates from Adam Smith . . . Wealth is a means to comfort . . .

Alfred Marshall [wrote that] . . . economics was the science which studies the ‘material requisites of well-being.’ Money . . . was a means to an end. But he did not define ‘well-being’ . . .

Lionel Robbins . . . defined economics as the science which ‘studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses . . . Robbins made scarcity the central, and indeed only, topic of economics . . . [I]t was not the materiality but the scarcity of goods which made them economic. 36 Robert Skidelsky, What’s Wrong with Economics? A Primer for the Perplexed 15-17 (2020).

Starting with a concise history of the subject is important because it helps us understand that economics is not and never has been a fixed science: while it may aspire to be like physics (subject to “physics envy”37See id. at 50; Tushnet, supra note 3; Horwitz, supra note 3.), economics will never be in a position to uncover fundamental laws of nature. Acknowledging this accomplishes two important tasks for us. First, it makes the definition of economics a topic worthy of discussion rather than a settled fact to be taken for granted. Second, it opens up the possibility that other “economicses” beyond the mainstream one might be imagined. We address each of these in the next two subsections.

2. The Contemporary Mainstream Definition

As noted above, the AEA defines economics as “the study of scarcity, the study of how people use resources and respond to incentives, or the study of decision-making.”38See American Economic Association, supra note 28. While this definition is clear in some ways, it is opaque in others. It hides, for example, the axioms to which, according to the scholars Christian Arnsperger and Yanis Varoufakis, neoclassical (mainstream) economics adheres: methodological individualism, methodological optimization, and methodological equilibration.39Christian Arnsperger & Yanis Varoufakis, Neoclassical Economics: Three Identifying Features, in Pluralist Economics 13-18 (Edward Fullbrook ed., 2008). Methodological individualism is the “idea that socio-economic explanation must be sought at the level of the individual agent.”40Id. at 15. Individual behavior is the fundamental locus of action, and it is gathered up into a societal outcome in a mechanistic additive manner. Methodological optimization further asserts that individual behavior is “preference-driven,” “a means for maximizing preference satisfaction.”41Id. at 16. These individuals optimize something—their preferences—and even if these preferences may be endogenous or complex, “homo economicus is still exclusively motivated by a fierce means-ends instrumentalism.”42Id. at 17. For further discussion of homo economicus (“economic man”), see infra Section II.C. Lastly, methodological equilibration closes the model by requiring that “agents’ instrumental behaviour is coordinated in such a manner that aggregate behaviour becomes sufficiently regular to give rise to solid predictions.”43Id. at 18. This is a decidedly circular argument: by first assuming behavior hovers around an equilibrium, economists then show that it will stay there. It says little about whether or how equilibrium will be reached in the first place. In total, these three axioms make for an unrealistic, incoherent, and fiercely defended neoclassical economics.

We will not engage here in a comprehensive philosophical consideration of economics; for now, it suffices to say that there is an extensive literature considering and critiquing the claimed naturalness, rationality, and objectivity of economic thought and practice.44See, e.g., Pluralist Economics (Edward Fullbrook, ed., 2008); Skidelsky, supra note 36; Rod Hill & Tony Myatt, The Microeconomics Anti-Textbook: A Critical Thinker’s Guide (2d ed. 2021). The core problem can be shown by noting economics’ failure to be either logically coherent or practically correct: it is both incoherent and wrong. For example, the First Fundamental Welfare Theorem essentially says that market competition will lead to an efficient (read: good) societal outcome: “Greed became the power which wills evil, but does good.”45 Skidelsky, supra note 36, at 27. This is Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” which is both a key article of faith for economists and an inexplicable logical leap in the original text.46 Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments 215 (Knud Haakonssen, ed., 2002). Smith elaborates:

The rich only select from the heap what is most precious and agreeable. They consume little more than the poor, and in spite of their natural selfishness and rapacity, though they mean only their own conveniency, though the sole end which they propose from the labours of all the thousands whom they employ, be the gratification of their own vain and insatiable desires, they divide with the poor the produce of all their improvements. They are led by an invisible hand to make nearly the same distribution of the necessaries of life, which would have been made, had the earth been divided into equal portions among all its inhabitants, and thus without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species . . . . In ease of body and peace of mind, all the different ranks of life are nearly upon a level, and the beggar, who suns himself by the side of the highway, possesses that security which kings are fighting for.

Id. at 215-16. To be clear: it is not, as claimed, logically coherent or empirically accurate.

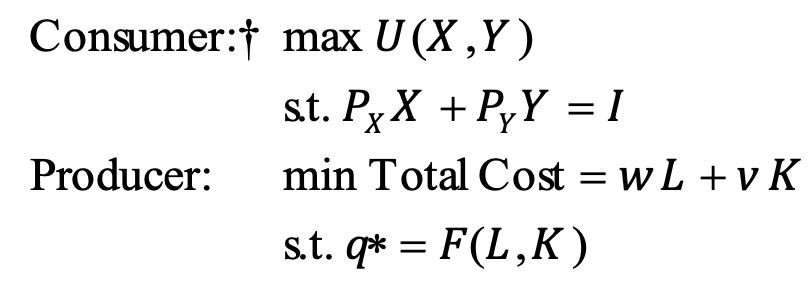

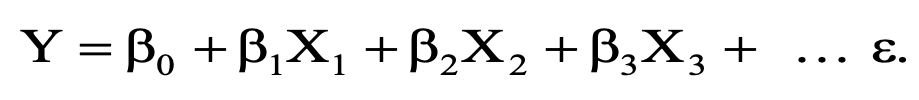

Economics is thus a science built of models that follow the three axioms above: methodological individualism, optimization, and equilibration. Eco-nomics textbooks start with prescriptive chapters of principles and instructions for how to “think like an economist,” i.e., according to these axioms. This way of thinking centers individuals, rationality, and choice under conditions of scarcity, and invisibilizes power, hierarchy, and society. Individuals are understood as consumers who seek to maximize their happiness (utility) subject to limited means (budget constraint). These individuals also appear in two roles on the production side of the economy: as workers or capitalists. As workers, individuals are no more human than they are as consumers: the model of labor supply is a simple adaptation of the model of utility maxi-mization. As owners of capital, individuals are even less human: the firm is understood to be making a production decision to make the most profit (rewritten as minimizing cost subject to a production technology). Thus, the guiding optimization problems are:

Note that the individual working-class person appears twice in these models: as the consumer maximizing their own utility and as the labor which is an input into production. This is important. Labor, L, is treated no differently than capital, K. But capital is physical machinery: the things that are required to make stuff. Labor, on the other hand, is people: the humans who do the making. But economists, the production function, and the owner of the firm (the capitalist) treat them the same. Moreover, economists and students of economics do not pay attention to the fact that they do this. It is presented as completely reasonable and not even worthy of notice, and yet it is a key moment in the commodification of humans, the transformation of human people into labor who sell their labor power to the capitalist.47Karl Marx’s theory of labor and labor power is both complex and central to Marxist Economics; it is also largely beyond the scope of the current Article. An insightful exposition can be found in David Harvey, A Companion to Marx’s Capital (2018): “So how then can the labor process, as a universal condition of possibility of human existence, be characterized? Marx distinguishes three distinctive elements: ‘purposeful activity, that is work itself . . . the object on which that work is performed, and the instruments of that work.’” 118-19 (quoting Karl Marx, Capital 284). Harvey further argues that this is where Marx “sets up the idea of a dialectic between technologies and social relations which will be significant.” Id. See also Karl Marx, Capital 186 (“In order to be able to extract value from the consumption of a commodity, [the capitalist] must be so lucky as to find, within the sphere of circulation, in the market, a commodity, whose use value possesses the peculiar property of being a source of value, whose actual consumption, therefore, is itself an embodiment of labour, and consequently, a creation of value. The possessor of money does find on the market such a special commodity in capacity for labour or labour power.”) This is, in our view, a violent dehumanizing moment in economics education that is not understood as such by those who do it, be they economists teaching this or students learning it.

What about the capitalist? The capitalist is in the shadows in these models. They are not the capital. They are the owner of the firm who magically does the profit maximization. So labor is labor: the laborer is not thought of as owning something of value, but as being a thing of value.48This, of course, parallels U.S. law’s treatment of enslaved Black people and their descendants prior to the adoption of the 14th Amendment. See, e.g., René Reyes, Religious Liberty, Racial Justice, and Discriminatory Impacts: Why the Equal Protection Clause Should be Applied at Least as Strictly as the Free Exercise Clause, 55 Ind. L. Rev. 275, 298 (2022) (“Indeed, Dred Scott v. Sandford made clear that enslaved Black people were not ‘persons’ whose liberty or property could not be taken from them; rather, they were property that could not be taken from white slaveowners.”). Marx wrote extensively about how he conceived the relationship between slavery and wage labor. See Harvey, supra note 47, at 129 (“Slavery becomes more brutal under the competitive lash of market integrations into capitalism, while, conversely, slavery exerts strong negative pressures on both wages and conditions of work.”). At the same time, however, Black Marxist theorists mount compelling critiques of Marx’s inattention to race, racism, and slavery. See Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition 2 (3d ed. 2020) (“Marxism is a Western construction—a conceptualization of human affairs and historical development that is emergent from the historical experiences of European peoples mediated, in turn, through their civilization, their social orders, and their cultures.”). According to Robinson, this includes “racialism: the legitimation and corroboration of social organization as natural by reference to the ‘racial’ components of its elements.” Id. Capital, on the other hand, is owned by the capitalist, and we generally do not spend time thinking about how he came to own that capital. Power is explicitly absent, but somehow only one set of people is “thingified.”

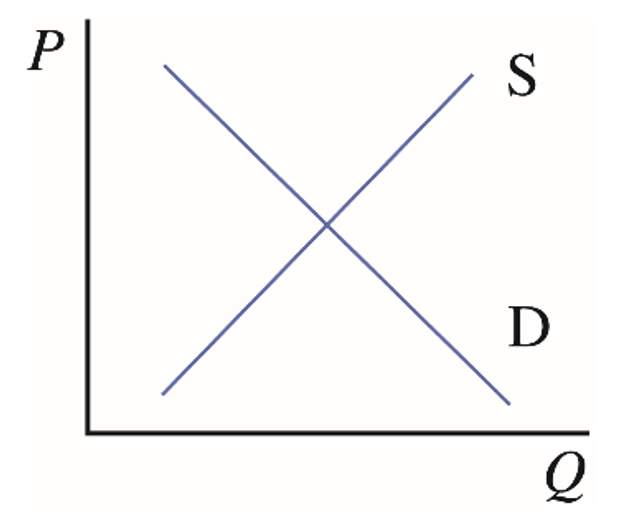

The next step in building the economic model is to put the consuming side and the producing side together: one is demand, the other supply, and they trade commodities. Economists put this into a helpful supply/demand graph, another of the discipline’s primary contributions to knowledge:

An economist’s first strategy in figuring something out is to try

to model it, and the first model to try is usually supply and demand. Hammer, nail.

Economics is built from these basic parts. Individuals seek to maximize their own well-being, firms seek to maximize their profit, and, “led by an invisible hand,”49 Smith, supra note 46, at 215. society arrives at a fair distribution of material goods. As Smith writes in his Theory of Moral Sentiments, “[i]n ease of body and peace of mind, all the different ranks of life are nearly upon a level, and the beggar, who suns himself by the side of the highway, possesses that security which kings are fighting for.”50Id. at 216.

It is clear, however, that there are some other parts implicitly built into the above. Most importantly, capitalism:

Capitalism is an economic system in which employers, using privately owned capital goods, hire wage labor to produce commodities for the purpose of making a profit.51 Samuel Bowles, Richard Edwards & Frank Roosevelt, Understanding Capitalism: Competition, Command, and Change 2 (4th ed. 2018).

Upon reflection, it appears that this definition of capitalism is merely a restatement of the central economic models described above, with the exception that the “consumer” is absent. At the same time, a definition of capitalism is almost never included in an introduction to economics textbook. Indeed, it is taken for granted to such a degree that many of the leading mainstream economics textbooks do not so much as include a single entry for capitalism anywhere in the index.52See, e.g., N. Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics (8th ed. 2017); Joseph E. Stiglitz & Carl E. Walsh, Economics (4th ed. 2006); Paul Krugman & Robin Wells, Essentials of Economics, (4th ed. 2015); Robert Frank, Ben Bernanke, Kate Antonovics, & Ori Heffetz, Principles of Economics: A Streamlined Approach, (4th ed. 2021). But cf. Bowles et al., supra note 51; The Core Team, The Economy: Economics for a Changing World (2019).

Where does that leave us? It seems that capitalism is economics and economics is capitalism. The definition also contains other key elements: private ownership of capital, hiring of wage labor, and the production of commodities. Crucially, the purpose of the entire system is made clear: profit. Not welfare, not human thriving, but profit. It is no wonder then, that economists would rather not have this be their definition.

3. Radical Definitions

Radical takes on economics generally start with acknowledgement that economics is not mere science, that it is capitalism as just explained, and that it involves substantial ideological work. From this perspective, capitalism is understood to be a hierarchical class system of power in which capitalists hire wage laborers to produce commodities. Moreover, this system is a racialized one. As Cedric Robinson writes, “[c]apitalism and racism were historical concomitants. As the executors of an expansionist world system, capitalists required racism in order to police and rationalize the exploitation of workers.”53 Cedric J. Robinson: On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance 79 (H.L.T. Quan ed., 2019). Ruth Wilson Gilmore states it similarly and succinctly: “[C]apitalism requires inequality, and racism enshrines it.”54Ruth Wilson Gilmore, The Worrying State of the Anti-Prison Movement, Soc. Just.: J. of Crime, Conflict & World Ord. (Feb. 23, 2015), http://www.socialjusticejournal.org/the-worrying-state-of-the-anti-prison-movement/. In other words, all capitalism is racial capitalism.

When we live within a system that demotes race to an individual, not systemic, consideration, this idea of the essential racism of capitalism can be difficult to grasp. As Destin Jenkins and Justin Leroy write in introducing their Histories of Racial Capitalism:

Racial capitalism is not one of capitalism’s varieties. It does not stand alongside merchant, industrial, and financial as a permutation, phase, or stage in the history of capitalism writ large. Rather, from the beginnings of the Atlantic slave trade and the colonization of the Americas onward, all capitalism, in material profitability and ideological coherence, is constitutive of racial capitalism.55Destin Jenkins & Justin Leroy, Introduction: The Old History of Capitalism, in Histories of Racial Capitalism 1, 1 (Destin Jenkins & Justin Leroy eds., 2021).

[R]acial capitalism is the process by which the key dynamics of capitalism—accumulation/dispossession, credit/debt, production/surplus, capitalist/worker, developed/ underdeveloped, contract/coercion, and others—become articulated through race.56Id. at 3.

Thus, “racial capitalism [is] the idea that capitalism cannot be understood outside of a relationship to power and race.”57 Davis et al., supra note 24, at 55.

In order to visibilize these “interlocking systems of domination that define our reality,” bell hooks terms this “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.”58 bell hooks: Cultural Criticism and Transformation (Media Education Foundation 1997), https://www.mediaed.org/transcripts/Bell-Hooks-Transcript.pdf. Joining hooks, we aim to visibilize capitalist (ideo)logics,59By using the term “capitalist ideologics,” we mean to describe the ways of thinking that shape logic within our capitalist system; these ways of thinking are to be understood as ideas, ideologies, and ideologics rather than merely simple “logic.” destabilize assumed understandings, and catalyze creative and critical reconsideration. In the economist’s disciplinary language, this Article engages with the binding of our self-imposed disciplinary constraints. Economists have chosen these constraints so completely that, as a discipline, economics does not even talk about them as such. They are, as sociologists describe how white Americans experience their white privilege in a racialized society, “like water to a fish . . . so natural that they are taken for granted, experienced as wholly legitimate.”60Michael K. Brown, Martin Carnoy, Elliott Currie, Troy Duster, David B. Oppenheimer, Majorie M. Schultz, & David Wellman, Whitewashing Race: The Myth of a Color-Blind Society 34 (2023).

These choices economists have made about what they do and how they do it are rarely subject to debate, and yet they are what we could call “strong assumptions,” shaping everything that comes after: mathematics, constrained maximization, individuals at the center, rational decision-making, value-free comparison, initial allocations of resources, individual choice, and agency. In addition to seeing and naming racial capitalism, radical economists bring all of this out into the open.

Myra Strober reflects on the puzzle of economists’ narrow

self-conception:

Scarcity, selfishness, and competition are each half of a dichotomy: scarcity/abundance; selfishness/altruism and competition/cooperation. What economic theory has done is largely to relegate the other half of the dichotomy to a place outside of economic analysis. That is, economics is almost always about scarcity, selfishness, and competition, but rarely about abundance, altruism, or cooperation. 61Myra H. Strober, Rethinking Economics Through a Feminist Lens, 84 Am. Econ. Rev. 143, 145 (1994).

In defiance of this hegemonic methodological uniformity, some scholars have proposed alternative approaches with transformative potential. William Darity, Jr., a founding thinker of Stratification Economics, writes that the approach he embraces “examines the structural and intentional processes generating hierarchy and, correspondingly, income and wealth inequality between ascriptively distinguished groups.”62William Darity, Jr., Stratification Economics: The Role of Intergroup Inequality, 29 J. Econ. & Fin. 144 (2005). In doing so, it “constitutes a systematic and empirically grounded—rather than anecdotally grounded—alternative to the conventional wisdom on intergroup disparity.”63Id. This idea that stratification economics is empirically grounded gestures towards the very real possibility that mainstream economics is not itself grounded in fact, that it may even be presenting a counterfactual narrative—i.e., one counter to the facts, particularly in the realms of race, racism, discrimination, and hierarchy. Narrative and the idea that facts are created, not merely measured, are both central to CRT; they will be core to Abolition Economics as well.64See infra Part III.A.

The feminist economist Julie Nelson writes that Feminist Economics recognizes that “various value-laden and partial—and, in particular, masculine-gendered—perspectives on subject, model, method, and pedagogy have heretofore been mistakenly perceived as value free and impartial in economics.”65Julie A. Nelson, Feminism and Economics, 9 J. Econ. Persps. 131, 132 (1995). For further discussion of the role of “value” in economics, see Dotan Leshem, Retrospectives: What Did the Ancient Greeks Mean by Oikonomia?, 30 J. Econ. Persps. 225 (2016). By examining structural processes not as aggregates of individual actions but as fundamentally structural, by building our theories on facts rather than anecdotes, and by interrogating the implicit values in our disciplinary practices, radical economists argue that the modeling of society can become more in line with reality. These scholarly communities assert that explicitly recognizing implicit choices and deliberately seeing unseen constraints will make a better economics. Put bluntly, facing reality is a necessary prerequisite for understanding reality. Economics has the potential to be both coherent and correct.

As the sociologists Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva argue, “‘White logic’ and ‘White methods’ . . . blind (or severely limit) many social scientists from truly appreciating the significance of ‘race’ (or, properly speaking, racial stratification).”66White Logic, White Methods, supra note 30, at 2.

The choice of a limited set of analytical and mathematical methods—individual constrained maximization as the core theoretical workhorse and causal regression as the core empirical workhorse—is limiting. Areas of behavior, identity, and welfare are defined out of economics and economic policy: they are lesser, softer, not the core functions of the economy or government. But as Strober reminds us, “by concentrating on scarcity, selfishness, and competition, economics makes it more difficult to redistribute power and economic well-being.”67 . Strober, supra note 61, at 145.

Abolition scholars argue that this is no accident. Rather, it is the point. The purpose of the system is, after all, profit.

By expanding economic thinking to incorporate critical, pluralist, and radical perspectives, including but not limited to Stratification, Feminist, or Marxist Economics, we hope to contribute to building an economics—as well as a Law & Economics—that can enable societal systems in which human thriving is not only possible, but is the goal. Economists on the whole choose to accept Adam Smith’s (and economics’) assertion that “the rich . . .

in spite of their natural selfishness and rapacity . . . without intending it, without knowing it, advance the interest of the society.”68 . Smith, supra note 46, at 215. We choose differently. We assert instead that such a claim is weak and inexplicable: to get somewhere “good” we must shed the bizarre assertion that bad produces good. This is one of the aims of Abolition Economics.

C. Abolition Economics as Praxis

In engaging in critical reflection on central methods and assumptions of mainstream economics, we endeavor to open questions and areas for reconsideration. In so doing, we want to declare unabashedly that we are making a specific scholarly and ideological argument. This stands in contrast to the way in which economists traditionally understand and describe their work—i.e., as a non-ideological quest for the “truth” guided by the methods of “social science.” Yet we maintain that mainstream economics is not an objective fact-finding mission, but rather a neoliberal ideological endeavor. There is no sharp line between positive and normative economics; what claims to be positive economics is infused with neoliberal assumptions and implicit values that serve the status quo capitalist systems and hierarchies. In this way, the argument of Abolition Economics is, at the outset and by definition, rendered unintelligible and illegitimate by the system of economics.

We therefore understand our deviation from disciplinary norms to be not our engagement in ideological work, but rather our engagement in counter-hegemonic ideological work. Scholars invariably engage in ideological work, and a primary element of that work is the denial of it. We argue that economics’ claim to objectivity is itself incorrect, unethical,

and ideological. It is incorrect because it systematically posits facts that do not match the actual facts, and unethical because the facts that it hides are those of inequality, oppression, and suffering.

The rest of this Article engages in Abolition Economics by considering (and reconsidering) various aspects of the economist’s endeavor: subjective statistics, constrained math, devaluation via invisibility, focus on individual causal links, dehumanized humans, atomizing characteristics, reductive language, disregarding hierarchy, and aspiring to equilibrium. This is our praxis of Abolition Economics: seeing how we do economics, dismantling it, changing it, and starting to build a new way.

II. Dismantle and Change

A. The Mathematical Industrial Complex

1. Subjective Statistics

The discipline of economics employs the languages of mathematics, statistics, and econometrics. This is a linguistic and methodological choice. To understand its significance, consider the sociologist Tukufu Zuberi’s definitions:

Mathematics is a system of statements that are accepted as

true. Mathematical statements follow one another in a definite order according to certain principles and are accompanied by

proofs . . . .Statistics is a form of applied mathematics. Often statistics are no more than the axioms applied, and they do not suggest the conditions of the correct applicability of the methods in the real world. Particular statistical methods’ applicability to social problems is determined by the users of social statistics.69 White Logic, White Methods, supra note 30, at 7 (emphasis added).

Further, we can note that Econometrics is understood as statistics applied and adapted to economic inquiry with a central focus on establishing causality both precisely and accurately.70 Joshua D. Angrist & Jörn-Steffen Pischke, Mastering ‘Metrics: The Path from Cause to Effect xi-xii (2014). Practically, what this means for economists is that they use econometric methodologies that they agree upon as valid, such agreement having been arrived at via consensus-building over time. And yet economists tend to disavow that process of building consensus, instead relying on a mathematical/scientific rigor justification to validate their methods: they are “correct.” By denying the role of consensus-building and norms in designing, structuring, and validating their methods, economists make it very difficult to question their own fundamental assumptions. Given that, as Zuberi argues, “current statistical methods were developed as part of the eugenics movement and continue to reflect the racist ideologies that gave rise to them,”71White Logic, White Methods, supra note 30, at 8. this is deeply problematic.

Economists have a long tradition of following what Dorothy Roberts describes as the “imperative for scientists to detach their study of biological race from societal racism” in order to erect an “imaginary wall . . . separating racial science from racial politics.”72Dorothy Roberts, Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-Create Race in the Twenty-First Century 47 (2011). In 1896, the statistician Frederick Hoffman prefaced his Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro (published by the AEA) as follows:

Being of foreign birth, a German, I was fortunately free from a personal bias which might have made an impartial treatment of the subject difficult. By making exclusive use of the statistical method and giving in every instance a concise tabular statement of the facts, I believe that I have made it entirely possible for my readers to arrive at their own conclusions, irrespective of the deductions I have made.73Frederick L. Hoffman, Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro v (1896).

This assertion of factual truth, while bold, is substantively not so different from the claims of most modern empirical economics papers: to use statistical and econometric methods to understand the facts and allow readers to “arrive at their own conclusions.” Hoffman’s analysis, thus begun, concludes 300 pages later as follows:

Nothing is more clearly shown from this investigation than that the southern black man at the time of emancipation was healthy in body and cheerful in mind . . .

What are the conditions thirty years later? The pages of this work give but one answer, an answer which is a most severe condemnation of modern attempts of superior races to lift inferior races to their own elevated position, an answer so full of meaning that it would seem criminal indifference on the part of a civilized people to ignore it . . .

It is not in the conditions of life, but in race and heredity that we find the explanation of the fact to be observed in all parts of the globe, in all times and among all peoples, namely, the superiority of one race over another, and of the Aryan race over all.74Id. at 311-12.

So how did Hoffman go wrong, and why should we care? Is his merely an errant voice of the past? We do know that, as part of the methodological history of social science, Hoffman is not alone: founding statisticians and creators of social facts consistently designed and deployed standard statistical methods to justify (and render invisible) white supremacy.75See Adam Markham, U.S. Universities Must Stop Honoring Racist Scientists of the Past, Equation (July 14, 2020), https://blog.ucsusa.org/adam-markham/u-s-universities-must-stop-honoring-racist-scientists-of-the-past/. These same statistical methods are among the most well-used ‘tools’ that economics brings to the law and economics collaboration; legal argument requires fact, and economists claim and are granted authority over what qualifies as quantitative fact.

While economists may vigorously deny involvement in justifying white supremacy, it is at least worth entertaining skepticism of methods with such a pedigree, and perhaps worthwhile to interrogate them closely. In 1897, the mathematician and sociologist Kelly Miller promptly rebutted Hoffman’s book, specifically taking aim at Hoffman’s claim of impartiality:

[F]reedom from conscious personal bias does not relieve the author from the imputation of partiality to his own opinions beyond the warrant of the facts which he has presented. Indeed, it would seem that his conclusion was reached from a priori considerations and that facts have been collected in order to justify it.76Kelly Miller, A Review of Hoffman’s Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, 1 Am. Negro Acad.: Occasional Papers 1 (1897) (book review).

Over a century on, Miller’s critique remains important to the discipline of economics and the collaborative endeavor of law and economics which relies on it. As the authors of The Hidden Rules of Race explain, “neoliberalism is a belief system and economic theory that was both fueled by and reinforces structural racism and racial rules.”77 Andrea Flynn, Susan R. Holmberg, Dorian T. Warren, & Felicia J. Wong, The Hidden Rules of Race: Barriers to an Inclusive Economy 5 (2017). We must reckon with the ways in which implicit ideological frameworks create an economics and a set of social facts that serve entrenched power systems. In bringing CRT to Law and Economics, we are endeavoring to uncover its capitalist and carceral ideologics. The act of quantifying, then, and quantifying in this particular way, is to be understood as a violent distortion and subjugation of a complex human reality. For example, the law routinely purports to be able to measure the “value” of a human life as the net present value of a person’s market earnings.78See Julianne Malveaux, Speaking Truth to Power: Race, Class, Gender, and the Intersection, 29 Rev. Black Pol. Econ. 53 (2002); Thomas J. Kniesner & W. Kip Viscusi, Promoting Equity through Equitable Risk Tradeoffs; 14 J. Benefit-Cost Analysis 8 (2023). See also W. Kip Viscusi, Extending the Domain of the Value of a Statistical Life, 12 J. Benefit-Cost Analysis 1 (2021); W. Kip Viscusi, Identifying the Legitimate Role of the Value of a Statistical Life in Legal Contexts, J. Legal Econ. 5 (2019); W. Kip Viscusi, The Value of Risks to Life and Health, 31 J. Econ. Literature 1912 (1993). Yet if market earnings are determined within the system of racial patriarchal capitalism, then values thus derived will reproduce that system’s racist, misogynist, exploitative valuation framework. In this way, the devaluation of humans is accomplished not only by the actual systems of the economy and the law but by the ideological systems of economics and law. Subjective statistics create, rather than measure, facts.

2. Constrained Math

Turning to economists’ use of math in economic theory, the structure imposed there is somewhat more explicit. Economists acknowledge this is unrealistic, but typically argue that it remains useful in elucidating underlying dynamics; this is the refrain of the intermediate microeconomics professor. Economists craft “toy models” and employ them to provide important insights, while more fully developed models form the backbones of important literatures. For example, economists employ a health capital function to model how early childhood influences such as environment, health, family, and schooling shape a person’s later life outcomes.79See, e.g., Michael Grossman, On the Concept of Health Capital and the Demand for Health, 80 J. Pol. Econ. 223 (1972). Just as a firm invests in physical capital and reaps financial returns, the parent and the individual “invest” in the person’s “health capital”, and then the individual reaps “returns.” The stock of health capital evolves from one period to the next, as investments bear fruit and disinvestments or illness impose costs. Economists show the remarkable flexibility and range of these models in providing insight into dynamic lifecycle processes that link early conditions with later health and life outcomes.80See, e.g., Douglas Almond & Janet Currie, Killing Me Softly: The Fetal Origins Hypothesis, 25 J. Econ. Persps. 153 (2011); Joshua Graff Zivin & Matthew Neidell, Environment, Health, and Human Capital, 51 J. Econ. Literature 689 (2013).

Do economists really think everything significant in life moves through that dynamic health capital equation? No, of course not; the authors themselves do not assert such an expansive purview. But economists do usually claim to be getting at something fundamental, asserting the strength of the analytical causal economic model—individual maximization under constraints—in revealing essential dynamics of how people’s lives evolve over time. This is how methodological individualism and optimization operate in practice.

At the same time, economists know that that is not all that matters, so discussions of hard-to-measure quantities like motivation and ability and altruism are incorporated—for completeness, in deference to reality, or in an effort to handle selection problems—but after the primary analysis, to extend it and to provide context. Isn’t there a possibility for structured qualitative analysis? Economics essentially says no, there is not, that is an oxymoron: structure = math. Moreover, despite the extensive dialogue and robustness testing involved in the dissemination and peer review of economics research, the literature rarely engages meaningfully with the legitimacy of modeling practices that shape or distort our “economic” understanding of social concepts: conceptualizing “health capital” and using mathematical tools (differential equations and investment theory) to model its evolution over time81See, e.g., Grossman, supra note 79.; formalizing a “marriage market” and discussing “quality” and “efficiency” of marriage “matches”82See, e.g., Betsey Stevenson & Justin Wolfers, Marriage and Divorce: Changes and Their Driving Forces, 21 J. Econ. Persps. 27 (2007).; or defining “poverty” as market income below a particular threshold and using the resultant numerical knowledge to shape policy intended to alleviate human suffering.83See, e.g., The History of the Official Poverty Measure, U.S. Census Bureau, https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/about/history-of-the-poverty-measure.html (last visited Oct 2, 2023). Mathematical analysis is understood to be strong economic analysis, notwithstanding its dependence on questionable assumptions or a severe mismatch between the mathematical model and the reality it purports to model.

3. The Mathematical Industrial Complex

Thus, we see that the math of economics is not just subjective and not merely constrained, but rather oriented with a specific positionality and worldview, and constrained and structured in a particular way to do particular things. As abolitionists, we put forward the idea that this should be understood as the Mathematical Industrial Complex (MIC). What do we mean by the MIC? First, consider the definition Critical Resistance provides for the Prison Industrial Complex (PIC):

The prison industrial complex (PIC) is a term we use to describe the overlapping interests of government and industry that use surveillance, policing, and imprisonment as solutions to economic, social and political problems.

Through its reach and impact, the PIC helps and maintains the authority of people who get their power through racial, economic and other privileges.84What is the PIC? What is Abolition?, supra note 26.

We define the MIC analogously:

The mathematical industrial complex (MIC) is a term we use to describe the way mathematics and statistics employ definition, quantification, and “equationification” to invisibilize, constrain, distort, and create “facts” about economic, social, and political problems.

These creations and distortions provide a shield of legitimacy, via explanation and justification, for authority that is actually derived illegitimately through the power dynamics and privilege structures of racial patriarchal capitalism.

The MIC serves core functions for economics, neoliberal ideologics, and racial patriarchal capitalism. Most importantly, radical and disruptive thought is rendered as illegitimate and incoherent, silenced before it can even speak.85See, e.g., White Logic, White Methods, supra note 30, at 21-22 (“By speaking of logic we refer to both the foundation of techniques used in analyzing empirical reality, and the reasoning used by researchers in their efforts to understand society. White logic, then, refers to a context in which White supremacy has defined the techniques and processes of reasoning about social facts. White logic assumes a historical posture that grants eternal objectivity to the views of elite Whites and condemns the view of non-Whites to perpetual subjectivity . . . White logic operates to foster a ‘debilitating alienation’ among the racially oppressed, as they are thrown ‘into a world of preexisting meanings as [people] incapable of meaning making.’”) (quoting Kelly Oliver, The Colonization of Psychic Space: A Psychoanalytic Theory of Oppression (2004)). Instead of allowing those oppressed by the system to be heard, the MIC “math-splains” over them to shape our collective understanding and reality. Hoffman’s freedom from “personal bias” in arriving at the conclusion of the “superiority of one race over another, and of the Aryan race over all” is to be understood as part of the MIC.86 Hoffman, supra note 73, at 311-12. A claim that intelligence can be measured by something called an “intelligence quotient”87See Roberts, supra note 72, at 40. (IQ) and that white people are more intelligent88Cf. Richard Hernstein & Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1994).

is part of the MIC. The assertion that production decisions are properly modeled as constrained cost minimization, and consequently workers are paid their marginal product, which is what they are worth, and they are not exploited, is part of the MIC.89 . See, e.g., Jeffrey M. Perloff, Microeconomics: Theory and Applications with Calculus 534 (5th ed. 2020). If the MIC gets to say how we think and what is fact, then the battle is lost before it starts. We now turn our attention to exploring this operation of the MIC in more detail to understand the ways in which it shapes what we can and cannot see, and what we make of what we do see.

B. What Matters

1. Efficiency Is Everything

Economics centers efficiency as a worthy goal, indeed the primary goal, of an economy. The prominence of efficiency in mainstream economics in general and in L&E in particular has been extensively criticized elsewhere in the legal academic literature.90See, e.g., Buchanan & Dorf, supra note 4, at 599-620; Kennedy, supra note 6; Jules L. Coleman, Efficiency, Utility, and Wealth Maximization, 8 Hofstra L. Rev. 509 (1980). Recently, for example, Neil Buchanan and Michael Dorf have argued that “efficiency-based analyses are frequently in practice used for ethically repugnant ends,”91Buchanan & Dorf, supra note 4, at 601. and that “neoclassical efficiency analysis does not deserve the glow of supposed objectivity that it has long enjoyed.”92Id. We need not revisit this line of criticism at length, and will merely add a few observations to connect the problems with efficiency to our abolitionist argument.

From an abolitionist perspective, the problem with efficiency is that it is racist. How and why is this so? Efficiency, the idea that society is “getting the most” from its resources, is implemented by testing for the absence of what are called Pareto improvements, trades in which one person can be made better off without making another person worse off. If no such trades are available, a situation is Pareto efficient. In this way, Pareto efficiency defers to the status quo distribution.

Employing Ibram X. Kendi’s definition of racism as “a marriage of racist policies and racist ideas that produces and normalizes racial inequities,”93 Kendi, supra note 14, at 17-18. we can see that Pareto efficiency is racist in at least two ways. First, Pareto efficiency is racist in a static way because the status quo distribution to which it defers is racially inequitable. The reasons for the racial inequity do not matter: deferring to it is racist, full stop. Second, Pareto efficiency is racist in a dynamic way because the processes of allocation and redistribution it deems legitimate are racially inequitable. Here, the reasons for the inequity do matter: primitive accumulation, colonialism, imperialism, slavery, theft, violence (the operations of racial capitalism) are deemed legitimate.94 Flynn et al., supra note 77. In this world, the innocent white applicant’s claim to a coveted admissions spot is legitimate, the Black applicant’s antiracist affirmative action claim is illegitimate, and the outcome is understood as fair and neutral while the racial inequity persists.95See Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President & Fellows of Harvard Coll., 600 U.S. 181, 385 (2023) (Jackson, J., dissenting) (rejecting majority’s conclusion that consideration of race in undergraduate admissions violates the Equal Protection Clause and arguing that the U.S. “has never been colorblind. Given the lengthy history of state-sponsored race-based preferences in America, to say that anyone is now victimized if a college considers whether that legacy of discrimination has unequally advantaged its applicants fails to acknowledge the well-documented ‘intergenerational transmission of inequality’ that still plagues our citizenry.”); Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 298 (Powell, J., plurality opinion) (arguing that practice of reserving 10 seats out of a class of 100 students creates “a measure of inequity in forcing innocent [white] persons . . . to bear the burdens of redressing grievances not of their making.”); Harris, supra note 30, at 1769-73 (discussing and critiquing Bakke).

The claim that Pareto efficiency is “not racist” rests on the false assertion that democracy + capitalism = meritocracy: we start at a neutral baseline, the means of distribution are legitimate, and consequently the resulting distribution is “earned.” Not only is it then impossible to achieve either equity or justice, but it appears as if efficiency is justice. While this is successful ideological work, it does not on its own achieve the creation of a world and a worldview that renders capitalism and its consequences fully natural. To accomplish that important goal, empirical work creating a set of facts is also necessary. We now turn our attention to this work.

2. What Is Counted Counts

As a discipline fully enmeshed with the MIC, economists focus on things that can be measured, and hopefully measured consistently, precisely, and accurately. Practically, this means that things that cannot be measured are frequently considered either not amenable to economic analysis or (conveniently) not worthy of economists’ attention. Further, it means that strategic institutional non-measurement—omission from official statistics, grouping to the point of invisibility—can function as methodological gerrymandering that enables the invisibility (and thereby the continued oppression) of disadvantaged groups.

One classic example of intentional invisibility is the dearth of reliable measures of firearms in the United States, the result of lobbying by the National Rifle Association (NRA).96See Samantha Raphelson, How The NRA Worked To Stifle Gun Violence Research, Nat’l Pub. Radio (Apr. 5, 2018), https://www.npr.org/2018/04/05/599773911/ how-the-nra-worked-to-stifle-gun-violence-research. Such absence hinders research showing that firearms may cause deaths, and requires clever strategies such as the economist Mark Duggan’s use of gun magazine subscriptions as a proxy to show “more guns, more crime”97Mark Duggan, More Guns, More Crime, 109 J. Pol. Econ. 1086 (2001). rather than “more guns, less crime.”98 John R. Lott, Jr., More Guns, Less Crime: Understanding Crime and Gun Control Laws (1998). The NRA is clearly an institution pursuing a particular agenda,99See A Brief History of the NRA, Nat’l Rifle Ass’n, https://home.nra.org/about-the-nra/ (last visited Oct. 30, 2023) (asserting that the NRA is “widely recognized today as a major political force and as America’s foremost defender of Second Amendment rights”). and in this case economists acknowledged that and endeavored to work around it. And yet economists do not engage in this sort of revelatory analysis (the economist version of investigative journalism) in every direction, but only in those that are of interest to them and for which strategies for quantification and the identification of a causal pathway can be crafted. Consequently, the insights are likely to stay comfortably within the bounds of the MIC.

3. The System Cannot be Seen from Within

This intentional framing, which accomplishes both focus and exclusion, works especially well in hiding important societal institutions and systems in plain sight. A core insight of CRT is the ubiquity of racial inequality and its perpetuation through facially race-neutral legal structures throughout American life.100See, e.g., Khiara M. Bridges, Critical Race Theory: A Primer 147–55 (2019); Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings, supra note 32, at xiii, xxxii. The institution of white supremacy, and its deep integration with societal institutions such as municipal organizations, education systems, the criminal legal system, and other organs of government, along with the institution of racial capitalism, the system of patriarchy—all of these are woven into the fabric of society, yet they are not amenable to economic analysis. They are too big, too enmeshed, too everywhere.101See Reyes, supra note 48, at 301 (arguing that the Supreme Court’s Equal Protection jurisprudence suggests that “racial inequality is too big to fail”). The MIC, thereby, keeps these systems safe, protected, and invisible in the quantitative ways that are deemed to matter. They are safe to keep making people unsafe.

Another canonical example can help us understand how the MIC accomplishes this important work. The minimum wage is one of the first applied examples to feature prominently in Principles of Economics courses. The short version according to the textbooks: by setting a wage that is higher than the ‘equilibrium’ wage that would arise in a ‘competitive labor market,’ a minimum wage causes unemployment and overall hurts those on the laboring side of the labor market, the people it intends to help.102See Mankiw, supra note 52; Hill & Myatt, supra note 44. This is one of the first opportunities new economics students have to practice using supply and demand theory on a practical question, and the result is simple and clear: markets good, government bad. If you talk to a college student who recently took a Principles of Economics course, we believe it is likely this minimum wage insight will be a memorable milestone.

There are, however, a number of problems with this. First off, in the real world, the model is wrong. Economists have substantial disagreement on the consequences of minimum wage regulations, including their quantitative, qualitative, contextual, and distributional effects.103See Hill & Myatt, supra note 44; Justin Wolfers, What Do We Really Know About the Employment Effects of the Minimum Wage, in The US Labor Market: Questions and Challenges for Public Policy 106 (Michael R. Strain ed., 2016). It is by no means clear that minimum wages are “bad.” Moreover, the story is historically whitewashed.104The hegemonic narrative of American history is that the New Deal provided broad social welfare programs to all Americans, thereby contributing to lifting individuals, communities, and the country out of the Great Depression. See, e.g., College Board, Advanced Placement Program, Advanced Placement U.S. History Course and Exam Description 352 (2023), https://apcentral.collegeboard.org/courses/ap-united-states-history. However, this narrative is incomplete in some ways and incorrect in others. See Flynn et al., supra note 77, at 23 (“In the 1930s and 1940s, many of the social and economic advances of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal rules – which aimed to provide worker protections and organizing rights, job creation, wage increases, and ultimately education and homeownership to middle-income Americans – were expressly not part of the social contract offered to blacks. And these exclusions were nationwide, not just southern: African Americans, other people of color, and women were functionally excluded from the initial Social Security Act, critical labor law provisions, homeownership, and the G.I. Bill.”). The federal minimum wage was established as part of the New Deal, aimed at providing basic protections to workers and thereby improving individual well-being. The definition of this as a “minimum” wage implies that it is indeed the minimum, that this is the least people should be paid, that it is the least people will legally be paid, and that people will not regularly be receiving wages below this. However, we know that this minimum was hardly universal.105See Flynn et al., supra note 77, at 23. Domestic, agricultural, and service occupations were exempted, exclusions that unsurprisingly and effectively harmed women and minorities disproportionately.106In the 1940 U.S. Census, 75% of Black women are listed in service occupations such as housekeepers, laundresses, other private household workers, attendants, cleaners, cooks, and waitresses. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States (1943); Steven Ruggles, Catherine A. Fitch, Ronald Goeken, J. David Hacker, Matt A. Nelson, Evan Roberts, Megan Schouweiler, & Matthew Sobek, IPUMS Ancestry Full Count Data: Version 3.0 [1940] (2021). As a consequence, 30% of women earned below this “minimum” wage in 1940, after the protections had taken effect.107In 1940, the weekly wage for a person working a 40-hour work week at minimum wage was .20 per week. Department of Labor, History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates Under the Fair Labor Standards Act, 1938 – 2009, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/minimum-wage/history/chart, accessed Dec. 1, 2023. In the 1940 U.S. Census, 30% of women reporting any wage/salary earnings earn less than this weekly wage. Sixteenth Census, supra note 106; Ruggles et al., supra note 106).

4. Invisibility Is Powerlessness

CRT scholarship seeks to expose and combat the widespread practice of erasing the narratives of marginalized communities and individuals from historical and legal memory.108See, e.g., René Reyes, Critical Remembering: Amplifying, Analyzing, and Understanding the Legacy of Anti-Mexican Violence in the United States, 26 Harv. Latin Am. L. Rev. 15 (2023); Nikole Hannah-Jones, Our Democracy’s Founding Ideals Were False When They Were Written. Black Americans Have Fought to Make Them True. N.Y. Times Mag. (Aug. 14, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/black-history-american-democracy.html; Harris, supra note 31. Abolition Economics seeks to do likewise. Consider the case of the minimum wage discussed above. Terming this wage a “minimum” then compounds the suffering of people who are below it: not only do they earn very little, perhaps less than they need to survive, but they are further diminished by having their lived reality denied by the data systems of the MIC. How is this accomplished? In 1940, with three-quarters of Black women in the labor force working in domestic service, a hugely disproportionate share of the women earning “implausibly low” wages (below half the minimum) were non-white.109In 1940, the weekly wage for a person working a 40-hour work week at minimum wage was .20 per week. History of Federal Minimum Wage Rates, supra note 107. In the 1940 U.S. Census, of women reporting wage/salary earnings less than half the minimum wage, approximately 50% were non-white, while only 10% of the U.S. population as a whole was non-white. Sixteenth Census, supra note 106; Ruggles et al., supra note 106. “Black women were subject to ‘superexploitation.’ . . . [T]he occupation of domestic worker to which the majority of Black women were relegated during the decades following slavery was associated with the very dangers that Black women had experienced during slavery: rape, sexual abuse, and harassment more broadly.”110 Davis et al., supra note 24, at 97. The meaning of this was clear to “the larger community of radical Black women activists,” who understood that the “gatherings of Black women on city street corners seeking work as domestics were known as “slave markets” not only because of the exceedingly low wages but also because the conditions of work were more akin to slavery than to wage labor.”111Id. at 98 (describing the Bronx in the 1930s). The New Deal’s exemption of domestic workers left these “slave markets” untouched, and economists’ acceptance of the minimum wage as a “minimum” rendered this oppression invisible.

These individuals’ experiences are certainly important in the reality of inequality, and, moreover, their inclusion or exclusion will substantively affect our measurement and understanding of that reality. And yet economists often deem these observations “outliers” and drop them prior to calculating the quantitative measures of inequality which become the facts of economic inequality.112For example, one of the co-authors of this Article spent her first economics research job assisting with analysis in which one method for creating 90-10 wage ratios was the exclusion of individuals who appeared to be earning such implausibly low wages (below half of the minimum wage). See, e.g., Lawrence F. Katz & David H. Autor, Changes in the Wage Structure and Earnings Inequality, in 3 Handbook of Lab. Econ. 1463, 1499–1500 (Orley C. Ashenfelter & David Card eds., 1999). Katz and Autor comment on these methodological issues: “The existence of a large number of outlier observations with extremely low weekly earnings (especially for women in 1940) motivates our presentation of overall inequality measures based on two different approaches to trimming this bottom tail. The first approach deletes the lowest 1 percent (and leads to findings that are quite similar to no deletions), and the second approach (following Juhn (1994)) deletes all individuals who earned less than half the contemporaneous Federal minimum wage. This second approach could potentially be misleading given substantial changes in the coverage and relative generosity of the Federal minimum wage over the period of study (especially from 1940 to 1950).” Id. (citing Chinhui Juhn, Wage Inequality and Industrial Change: Evidence from Five Decades (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 4684, 1994)). This is how the MIC can distort our understanding of lived realities, both in the creation of a historical narrative and in the establishment of standards for appropriate methodology.

Similarly, Becky Pettit argues that in the context of what is termed the “mass incarceration”113See Dylan Rodríguez, ‘Mass Incarceration’ as a Misnomer, 26 Abolitionist (2016). “‘Mass Incarceration’ has become a misleading, largely useless, and potentially dangerous term – a newly designated keyword, if you will, in the steadily expanding political vocabulary of post-racialism.” Id. of Black men, the exclusion of institutionalized individuals from the Current Population Survey renders these men invisible and biases macroeconomic measures.114 Becky M. Pettit, Invisible Men: Mass Incarceration and the Myth of Black Progress 4–5 (2012).

The decades-long expansion of the criminal justice system has led to the acute and rapid disappearance of young, low-skill African American men from portraits of the American economic, political, and social condition. While the expansion of the criminal justice system reinforces race and class inequalities in the United States, the full impact of the criminal justice system on American inequality is obscured by the continued use of data collection strategies and estimation methods that predate prison expansion.115Id. at 3.

These biases are not neutral, serving to hide some of the most egregious systemic consequences of racial capitalism. White supremacy and “white methods” work hand-in-hand.

5. What Matters

The result of all of this—the intentional result—is that the deck is stacked so that capitalism will always look terrific: efficient, good, successful. The “facts” that are “analyzed” by “economics” will never, can never, lead to a conclusion that blames capitalism. The entire endeavor—the facts, the policy, and the assessment of it all—not only disregards the “outliers” who don’t fit the political, economic, or social model, but also actively oppresses them. The devaluing of stories and lives via narrative and policy is linked with the devaluing via actual measurement and assessment of the reality, establishing a cycle whereby policy can be successful at achieving aims that are narrowly defined within the sphere already deemed worthy.

The field of economics has, of course, made important headway, as economists have thoughtfully reevaluated poverty and inequality116 . See, e.g., Opportunity Insights, https://opportunityinsights.org/ (last visited Oct. 23, 2023); Esther Duflo, Human Values and the Design of the Fight Against Poverty (Lecture, May 2012), https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/documents/TannerLectures_EstherDuflo_draft.pdf. and are issuing and answering calls to pay long-overdue attention to extreme inequality and injustice.117See The Sadie Collective, An Open Letter to Economic Institutions in The Face of #BlackLives Matter, Medium (July 16, 2021), https://sadiecollective.medium.com/open-letter-to-economics-blm-5b38100e59b5; William B. Spriggs, Is now a teachable moment for economists? An open letter to economists from Bill Spriggs, Fed. Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2020), https://www.minneapolisfed.org/~/media/assets/people/william-spriggs/spriggs-letter_0609_b.pdf. Yet for economics to achieve its ambitions, we must be clear about what it means to establish facts and to pursue certain lines of inquiry in certain ways. We must pay attention and respect to all realities. This includes the realities of those in elite positions, whose privilege is not only dependent on hiding the full scope of their privilege, but which also affords them the power needed to maintain it. This also includes the realities of those who are marginalized, whose oppression is not only facilitated by the invisibility of their suffering but which also deprives them of the agency required to resist it. To do so, we next consider the ways in which economics conceptualizes individual people and the societies in which they live.

C. People

1. Economic Man Is