The Right to Education: Where We Go Next

By: Daniel Baum

Associate Editor, Vol. 26

This blog calls on scholars and practitioners to advocate, and for courts to hold, that every student in this country—no matter whether they live in Orange, Wayne, or Washtenaw County, or whether their skin is Black, white, or neither—possesses a fundamental right to education that the government must affirmatively provide. This contention follows from two recent, landmark decisions: Gary B. v. Whitmer, which found that a basic minimum education is a fundamental right under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and Obergefell v. Hodges, which provided insight into the proper analytic framework for assessing due process claims. Although the Gary B. decision was later vacated and thus lacks precedential value, its novel holding, particularly when combined with Obergefell’s guidelines, merits continued review and adoption in scholarship and practice alike.

- Gary B. and the newfound fundamental right to education and literacy

In 2018, a group of seven Detroit Public School students filed a class action lawsuit against then-Governor Rick Snyder. The plaintiff-students alleged that the conditions in their schools were so abhorrent—schools full of rodents, teachers without degrees, textbooks for the wrong classes[i]—that they were effectively being denied access to even a minimally adequate education.

This, the students contended, violated their fundamental right to literacy under the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In addition, the students advanced an equal protection challenge, alleging disparate levels of school funding along racial lines.

The U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan dismissed the suit, holding that no such constitutional right to literacy existed, and that plaintiff-students failed to state an equal protection claim. Gary B. v. Snyder, 329 F. Supp. 3d 344 (E.D. Mich. 2018).

The students appealed and the U.S. Circuit Court for the Sixth Circuit affirmed in part and reversed in part. In a 2-1 decision, the Court affirmed the District Court’s holding with respect to the equal protection challenge but reversed its due process finding. After thoroughly examining relevant substantive due process[ii] and education funding[iii] case law, the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause does provide students with a fundamental right to a basic minimum education, principally one that provides students with access to literacy. Gary B. v. Whitmer, 957 F.3d 616, 648 (6th Cir).

The Court relied on several factors in arriving at this novel holding. Animating its analysis was the notion that without an education, especially the literacy it provides, children will be unable to participate in our democracy. Gary B., 957 F.3d at 642. The Court further considered the history of education in our country—a cornerstone of substantive due process analysis—and its evolution to the point of near universal expectation. Id. at 662. Importantly, the Court also explored the connection between race and education, finding that access to the latter helps mitigate the ongoing inequalities of the former. Id. at 648.

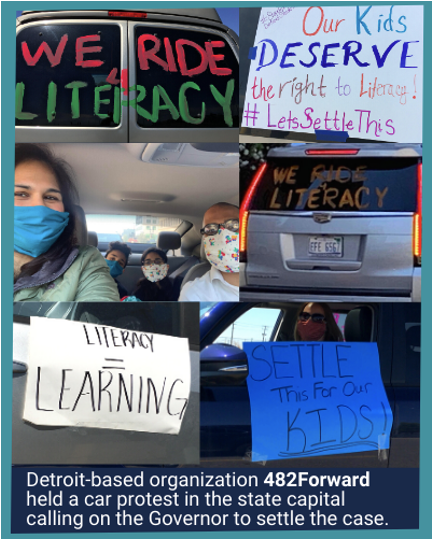

Following the Court’s ruling, Governor Gretchen Whitmer and plaintiff-students entered into a settlement agreement: the state agreed to provide $2.72 million in literacy-related funding to Detroit Public Schools and $280,000 to the seven plaintiffs for their continued educations.[iv] The Sixth Court ultimately heard the case en banc and vacated the panel’s decision, Gary B. v. Whitmer, 958 F.3d 1216 (6th Cir. 2020), thus leaving it without precedential value.

- Obergefell and its implication on substantive due process analysis

Certain rights are considered so fundamental that no amount of procedural due process exists that may strip individuals of such rights, absent, of course, a compelling government reason to do so. Some of these fundamental rights include the right of interracial couples to marry,[v] the right of unmarried persons to use contraception,[vi] the right to access an abortion,[vii] and the right to intimate sexual relations.[viii] But how these so-called substantive due process rights come to be in the first instance has been subject to considerable debate—and, some may add, confusion—inside the bench, bar, and constitutional law classes alike.[ix]

Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Obergefell addressed many questions about substantive due process analysis, providing answers that will guide courts on how to assess such claims in the future. At a high level of generality, Justice Kennedy endorsed Justice Harlan’s dissent in Poe. v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, for the proposition that a balancing act, not a strict formula, should dictate substantive due process review.[x] But before addressing the specific issues before the Court,[xi] Justice Kennedy countered the view, shared by some members of the Court, that substantive due process rights are not to be expanded: “When new insight reveals discord between the Constitution’s central protections and a received legal stricture, a claim to liberty must be addressed.”[xii] This judicial requirement, Justice Kennedy wrote, stems from the notion that the ratifiers of the Bill of Rights and the Fourteenth Amendment “did not presume to know the extent of freedom in all of its dimensions, and so they entrusted to future generations a charter protecting the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.[xiii] With the proper background in mind, the Court answered both questions in the affirmative—leading to the legalization of same-sex marriage nationwide.

While Obergefell’s landmark holding was worthy of celebration in and of itself, the opinion also provided two doctrinally significant moves that will help animate future substantive due process review. First, Justice Kennedy blurred the line between so-called “negative” substantive due process rights and “positive” substantive due process rights—the latter being certain rights the government must affirmatively provide. Justice Kennedy found support for this proposition from his Lawrence decision, writing that while “Outlaw to outcast may be a step forward” (Lawrence held unconstitutional Georgia’s anti-sodomy laws), “it does not achieve the full promise of liberty.” Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 667. Thus, Obergefell required the government to take action—in this case, issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples—rather than merely requiring the government not to do something. While issuing marriage licenses is arguably ministerial in nature, the blurring of such an arbitrary distinction between negative and positive substantive due process rights is significant for recognition of future fundamental rights. Second, and perhaps more implicitly, the Court mixed equal protection review with due process review—reasoning that the former actually helps to guide the latter. “Rights implicit in liberty and rights secured by equal protection may rest on different precepts and are not always co-extensive, yet each may be instructive as to the meaning and reach of the other.”[xiv] Justice Kennedy’s comingling of Fourteenth Amendment rights—race with respect to the equal protection clause and marriage with respect to the due process clause—may support a similar analysis in education cases where race and funding are often inexplicably linked.[xv]

- Where we go next: examining Gary B. in light of Obergefell

“The identification and protection of fundamental rights is an enduring part of the judicial duty to interpret the Constitution.” Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 663. We are thus left in a juridical universe in which courts no longer require a formalistic recitation when evaluating substantive due process claims, but rather rely on a reasoned judgement approach that “respects our history and learns from it without allowing the past alone to rule the present.” Id. at 664. Moreover, Justice Kennedy’s opinion also mitigated, if not eliminated, the positive versus negative substantive due process dichotomy and morphed together liberty and equality in such review. Thus, scholars, practitioners, and courts alike ought to utilize such an analytical framework in assessing the fundamental nature of the right to a basic minimum education.

[i] Dana Goldstein, Detroit Students Have a Constitutional Right to Literacy, Court Rules, N.Y. Times (April 27, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/27/us/detroit-literacy-lawsuit-schools.html.

[ii] Specifically, the Court analyzed Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S. 644, 135 S. Ct. 2584, 192 L. Ed. 2d (609) (2015) and Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702, 117 S. Ct. 2258, 138 L. Ed. 2d 772 (1997).

[iii] The Court examined Plyler v. Doe, 457 U.S. 202, 102 S. Ct. 2382, 72 L. Ed. 2d 786 (1982) and San Antonio Indep. Sch. Dist. V. Rodriquez, 411 U.S. 1, 93 S. Ct. 1278, 36 L. Ed. 2d 16 (1973).

[iv] History is Made: Groundbreaking Settlement in Detroit Literacy Lawsuit, Public Counsel (May 14, 2020), http://www.publiccounsel.org/stories?id=0303.

[v] Loving v. Virginia, 338 U.S. 1, 87 S. Ct. 1817, 18 L. Ed. 2d 1010 (1967).

[vi] Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 85 S. Ct. 1678, 14 L. Ed. 2d 510 (1965).

[vii] Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 93 S. Ct. 705, 35 L. Ed. 2d 147 (1973).

[viii] Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 123 S. Ct. 2472, 156 L. Ed. 2d 508 (2003).

[ix] Although the evolution of due process doctrine is beyond the scope of this piece, I’d refer readers to the Legal Information Institute: https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/amendment-14/section-1/due-process-of-law.

[x] Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 663-64.

[xi] The issues before the Court were whether states must issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and, relatedly, whether states must recognize same-sex marriages performed lawfully in other states.

[xii] Obergefell, 576 U.S. at 664.

[xiii] Id. (emphasis added).

[xiv] Id. at 644.

[xv] Alisa Chang and Jonaki Mehta, Why U.S. Schools Are Still Segregated—And One Idea To Help Change That, NPR (July 7, 2020), https://www.npr.org/sections/live-updates-protests-for-racial-justice/2020/07/07/888469809/how-funding-model-preserves-racial-segregation-in-public-schools.