Reflections from Rebellious Lawyering Conference 2020

by Becky Wasserman

Associate Editor, Vol. 25

This year, a group of Michigan law students – including members of the Michigan Journal of Race & Law – traveled to New Haven, Connecticut for Yale Law School’s annual Rebellious Lawyering Conference. The mission of the conference is to convene:

. . . practitioners, law students, and community activists from around the country to discuss innovative, progressive approaches to law and social change. The conference, grounded in the spirit of [UCLA Law professor and public interest lawyer] Gerald Lopez’s Rebellious Lawyering, seeks to build a community . . . seeking to work in the service of social change movements and to challenge hierarchies of race, wealth, gender, and expertise within legal practice and education.[1]

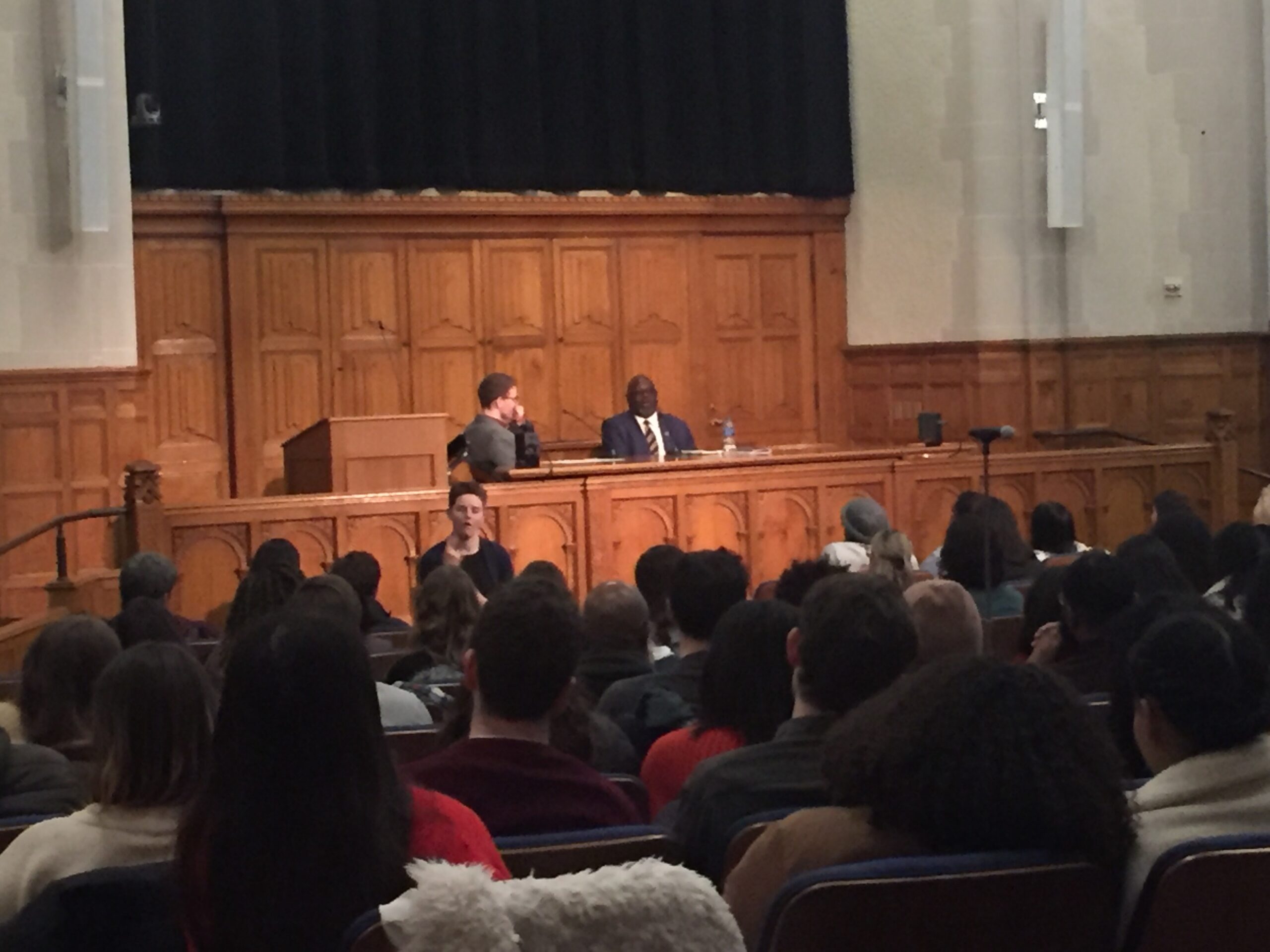

The Honorable Carlton W. Reeves gives the keynote address at the 2020 Rebellious Lawyering Conference.

Sticking true to that mission, the opening keynote address was delivered by The Honorable Carlton W. Reeves of the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi. Rather than focus on his many impactful decisions from the bench,[2] Judge Reeves spoke at length about his childhood in Yazoo City, Mississippi and his experience as a black student in a newly racially integrated classroom. From that young age, he recognized the power of judges to do justice in a world of deep injustice. It was an important reminder for progressive law students that the federal judiciary has historically served as a key tool in expanding civil rights and individual liberties in this country, and can continue to serve that role in the future with more people like Judge Reeves on the bench.

Most of the weekend was made up of panels on a wide range of topics. The hardest part was choosing which to attend! The sessions ranged from “How Social Media Surveillance Funnels Youth into the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” to “Movement Lawyering in Support of Black, Indigenous, and Palestinian Rights,” to “Collective Action and Environmental Justice.” One panel that I attended at the beginning of the weekend and particularly enjoyed was “Hope in Times of Crisis: Climate, Immigration and Criminal Justice.” It featured Ravi Ragbir from New Sanctuary Coalition of New York and Jeanne Ortiz-Ortiz of Pro Bono Net. As an immigrant rights organizer and activist, Mr. Ragbir has been in the national spotlight recently for a federal case he brought to prevent his imminent deportation, arguing on First Amendment grounds.[3] The Second Circuit declared that there was a “plausible, clear inference” that Mr. Ragbir’s public criticism of the Trump administration immigration policies “played a significant role in the recent attempts to remove him.” [4] At the conference, Mr. Ragbir challenged the audience of law students to learn about the law in order to dismantle it for a more just system. He stressed that as the climate crisis intensifies, the United States will especially need to reconsider its immigration and refugee laws in order to respond to climate refugees.

Ms. Ortiz-Ortiz spoke from the perspective of an attorney who has worked to expand legal access to communities after natural disasters, including in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. She encouraged lawyers who want to volunteer their legal skills to communities in crisis to listen to what survivors actually need instead of presuming they have the answers. In the midst of what can feel like existential crises on many fronts, both Ms. Ortiz-Ortiz and Ms. Ragbir expressed their hope in seeing movements for social change connect and show up for each other since Trump’s election in 2016. None of these issues exist in silos; therefore, our solutions must involve building intersectional movements with the power to change our laws, politics, and way we exist in community together.

Another talk I attended was called “Decarceration, Abolition and Liberation: We Don’t Need Police in Reproductive Justice” and featured Desireé S. Luckey, Esq. and Moira Tan. Instead of a traditional panel, the speakers had the audience break into groups and discuss how incarceration impacts people’s reproductive choices. My group spoke about the experience of pregnant people while incarcerated, and how they are often still shackled while giving birth.[5] Other pregnant women receive inadequate prenatal care and medical attention, with some giving birth alone in their cells without any medical assistance.[6] Our group talked about the tension between fighting for improved conditions for pregnant people while incarcerated and ultimately fighting for prison abolition. Right now, “prisons are the default solution for a vast range of social problems,” one group member said. “We need to strengthen and build our other public institutions to move away from incarceration towards true liberation.”

A major highlight of the weekend was meeting law students from other schools with shared interests and goals for their legal education. There were lunch discussion breakout groups where participants could talk about queer liberation, movement lawyering, impact justice or any other number of topics. The People’s Parity Project hosted a happy hour to build connections between students trying to shift law firm employment practices. Lastly, there were caucus breakout groups where people with shared identities could build relationships. Overall, conference participants were challenged to not be afraid to use or dismantle the law in the interest of justice, and to take bold action as future lawyers in support of the public good.

[1] Rebellious Lawyering Conference 2020, https://reblaw.yale.edu (last visited Feb. 22, 2020).

[2] See, e.g., Jackson Women’s Health Org. v. Currier, 349 F. Supp. 3d 536 (S.D. Miss. 2018) (striking down a Mississippi law banning abortion after 15 weeks’ gestation); Campaign for S. Equal. v. Bryant, 64 F. Supp. 3d 906 (S.D. Miss. 2014) (declaring Mississippi’s same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional).

[3] See The Editorial Board, ICE Tried to Deport an Immigration Activist. That May Have Been Unconstitutional., N.Y. Times, Apr. 27, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/27/opinion/sunday/ice-deportation-activists.html.

[4] Ragbir v. Homan, 923 F.3d 53, 71 (2d Cir. 2019).

[5] See Lori Teresa Yearwood, Pregnant and shackled: why inmates are still giving birth cuffed and bound, The Guardian (Jan. 24, 2020, 5:30 PM), https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/jan/24/shackled-pregnant-women-prisoners-birth.

[6] See Roxanne Daniel, Prisons neglect pregnant women in their healthcare policies, Prison Policy Initiative (Dec. 5, 2019), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/12/05/pregnancy/.