The Disconnect in Vacatur Laws, Human Trafficking, and Race

By Shawntel Williams

Associate Editor, Vol. 27

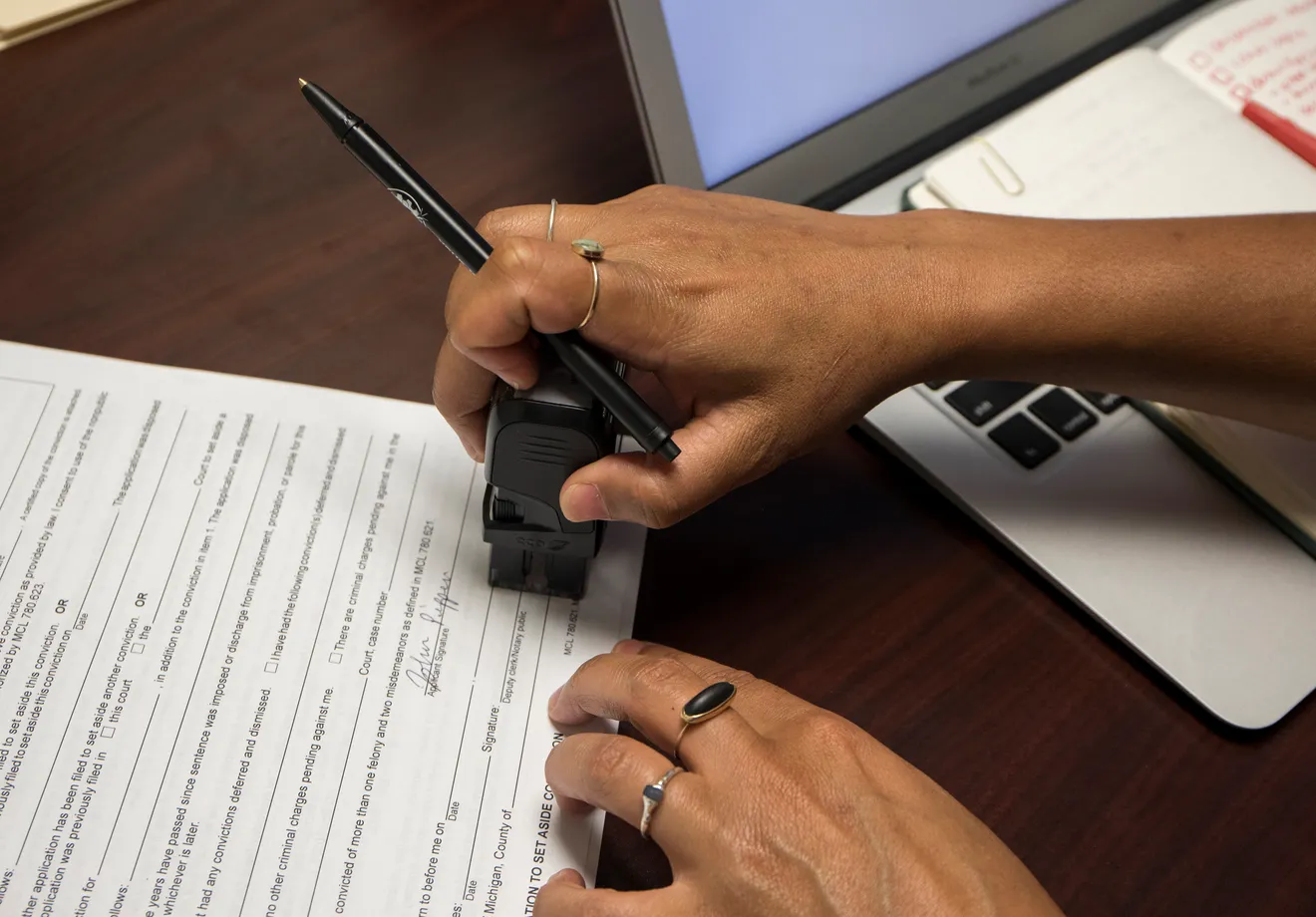

Survivors of human trafficking who have criminal records stemming from their victimization have some redress in vacatur laws. These laws allow victims of human trafficking the chance to start anew with a clean slate by expunging their arrests and convictions. Well, that is the stated goal at least. The strict qualification requirements for expungement eligibility and the non-existence of a federal vacatur statute prevent many victims from accessing these remedies.[1] As people of color are both disproportionately victims of human trafficking and disparately impacted by the criminal legal system due to structural racism, it is important to push for better policymaking that increases access to expungement.[2] Expungement helps free individuals from the collateral consequences like limited access to housing, education, and employment that they inevitably confront due to their criminal record.[3] Further, expungement can allow people the opportunity to clear their record “based on principle” and move forward with their lives knowing they are no longer criminalized for being a victim of human trafficking. [4]

History of Human Trafficking Vacatur Laws

Various vacatur laws were created to counter the injustice survivors of human trafficking face when followed by a criminal record stemming from their victimization.[5] An individual’s eligibility for expungement or vacatur, as well as the qualified offenses that can be cleared, vary widely from state to state. Polaris Project provides a detailed report card of each state’s statute provisions on criminal record relief.[6] Each state is graded on multiple factors including, but not limited to, range of relief (whether the statutes allow for vacatur, expungement, or record sealing), timeline (how long survivors must wait before applying for expungement), offenses covered (whether the statute covers the broad list of crimes survivors are prosecuted for), and nexus to trafficking (how close the offense needs to be to the trafficking).[7] Despite many states’ failing grades, having some relief is better than none. There are a few states, like Virginia, that do not allow for any expungement of crimes that victims were forced to commit while trafficked.[8]

New York was the first to pass human trafficking vacatur laws in 2010, but many states have followed suit.[9] As of right now, New York only allows vacatur for sex-related crimes.[10] Restrictions like these disregard victims of labor trafficking that have arrests and convictions stemming from their victimization. It also prevents many deserving victims, despite credible human trafficking experiences, from applying because they do not have a prostitution conviction.[11] Some states have expanded their statutes to cover non-prostitution and sex-related offenses which expands the relief victims can receive.[12] This is especially important, as many victims are forced to commit crimes for their trafficker’s financial benefit (such as theft and drug possession).[13] The National Survivor Network conducted a survey in 2016, where the results indicated that 90.8% of the trafficking survivors surveyed had been arrested at some point, for various charges.[14] What is more drastic, however, is that over half of these respondents reported that 100% of their arrests were directly linked to being trafficked.[15] Without the relief of vacatur laws, having these crimes on an individual’s record creates barriers in their civic life like meaningful employment and housing.[16] Nevertheless, there are still many drawbacks within the existing criminal record relief statutes that inhibit its purpose of providing victims justice.

Organizations such as the Ohio Justice and Policy Center provide expungement services to victims of human trafficking using the Safe Harbor Law (H.B. 262, R.C. 2953.38) that came into effect in 2012.[17] However, to be eligible for overall conviction expungement, an individual in Ohio must have at least one conviction for soliciting, loitering to engage in solicitation or prostitution.[18] This requirement severely limits the number of people eligible for safe harbor expungement in Ohio, as many victims of human trafficking do not possess a conviction for any of the above. There are legislative efforts ongoing to remove these predicate offenses and allow many more survivors of human trafficking a “path to expungement.”[19] Senators Teresa Fedor and Stephanie Kunze have championed these legislative efforts, with Kunze explaining that the Expanding Human Trafficking Justice Act will be a “simple solution to an outdated law that is holding back progress for survivors.”[20]

The Disproportionate Effect on People of Color

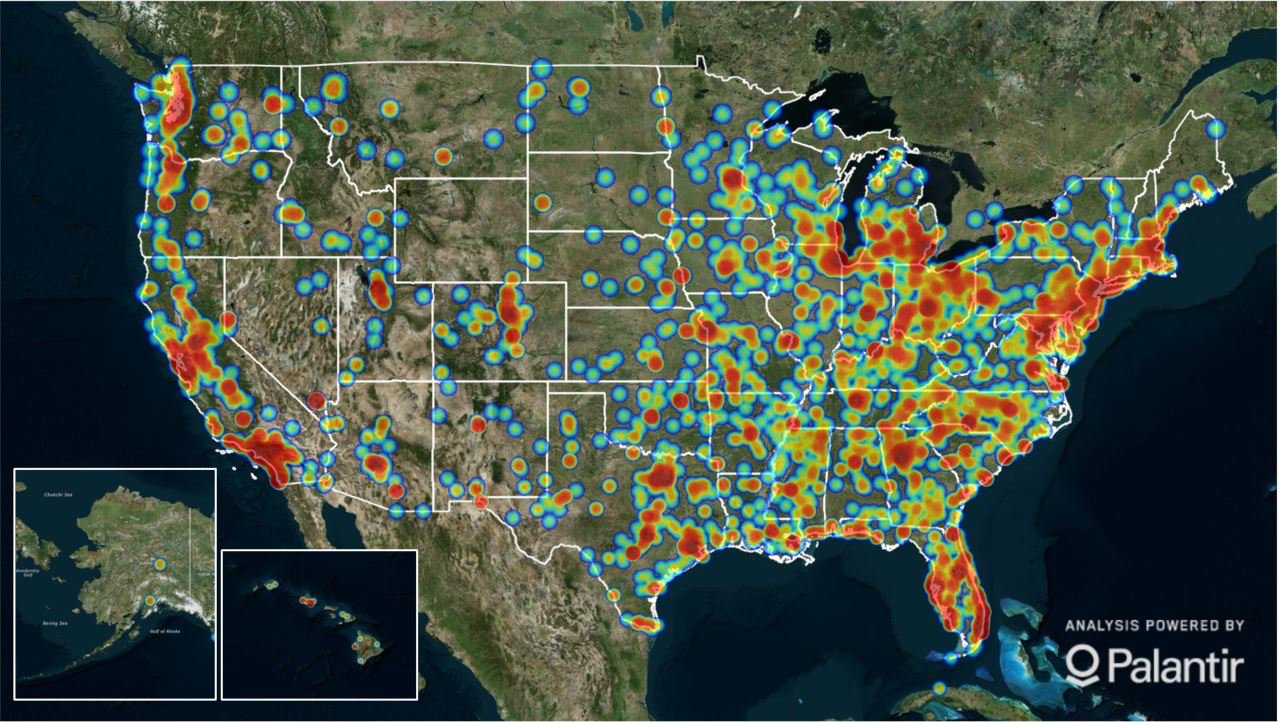

The disproportionate number of convictions for people of color, which stem from cumulative effects of systemic racism, make vacatur laws even more important if we are to achieve racial justice.[21] According to a two-year study conducted from 2008 to 2010, 40% of victims of sex trafficking were Black.[22] Despite this, these victims are often not acknowledged as victims and are often criminalized for their actions. Forty-two percent of adult prostitution arrests were Black while 51% of juvenile prostitution arrests were Black children.[23] Taking in these statistics, it is clear that we should conduct extensive research on racial breakdowns of human trafficking victims and their connection to the criminalization these survivors face as a result of their trafficking.

In her article “The Racial Roots of Human Trafficking”, Cheryl Nelson Butler highlights how the modern anti-trafficking movement has “failed to understand and address the racial contours of domestic sex trafficking.”[24] She goes on to say that the systemic failure […] to accurately identify people of color as trafficking victims” prevents people of color from meaningful access to “victim-centered services and resources.”[25] Ignoring the intersection of race, gender, age, sexual orientation and identity, socioeconomic status, and other social identities leads to shortcomings in identifying and assisting minority victims.[26] These shortcomings are exacerbated when victims of human trafficking are misidentified as “illegal migrants or criminals deserving punishment.”[27] Instead of providing support to victims of human trafficking, many are subject to “arrest, detention, deportation, or prosecution” leading many victims wary of seeking help from law enforcement.[28] These erroneous convictions have pushed states to create vacatur laws that still fall short of providing adequate redress to victims.

Moving Forward

There are several areas of concern that need to be researched to address the disparities racial minorities face in their access to victim-centered services as human trafficking survivors. First, an extensive study on the demographics of domestic human trafficking should be completed on a national level.[29] This will allow for more targeted policymaking that adequately addresses the intersection of factors that lead to misidentification and overcriminalization of victims of color. Second, there must be a push for the creation of a federal vacatur statute (that states can mirror) or improved state statutes that expand the relief victims of human trafficking can receive.[30] This expansion can come in many forms, i.e., broadening the crimes that are expungable, removing predicate offenses, and reducing the procedural barriers people must go through with their expungement applications. While vacatur statutes do not completely offset the overcriminalization of people of color, they provide an avenue to expungement and allow survivors of human trafficking to move forward with their lives without the barriers a criminal record brings upon reentry.

[1] Ashleigh Pelto, Criminal Record Relief for Human Trafficking Survivors: Analysis of Current State Statutes and the Need for a Federal Model Statute, 27 Mich. J. Gender & L. 473, 480-481 (2021).

[2] U.S. Dep’t of Just., Characteristics of Suspected Human Trafficking Incidents, 2008-2010 6 tbl. 5 (2011), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/cshti0810.pdf.

[3] J.J. Prescott & Sonja B. Starr, The Case for Expunging Criminal Records, N.Y. Times (March 20, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/20/opinion/expunge-criminal-records.html.

[4] Bianca Bruno, Expungement Law Helps Human Trafficking Victims Move Forward, Courthouse News Service (Feb 2, 2018), https://www.courthousenews.com/expungement-law-helps-human-trafficking-victims-move-forward/

[5] S. 674, 2021-2022 Leg. Sess. (N.Y. 2021).

[6] State Report Cards, Polaris, https://polarisproject.org/grading-criminal-record-relief-laws-for-survivors-of-human-trafficking.

[7] Erin Marsh, Brittany Anthony, Jessica Emerson, & Kate Mogulescu, State Report Cards – Grading Criminal Record Relief Laws for Survivors of Human Trafficking, Polaris 14-17 (2019), https://polarisproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Grading-Criminal-Record-Relief-Laws-for-Survivors-of-Human-Trafficking.pdf.

[8] Theresa Vargas, Sex trafficking survivors are treated as criminals in Virginia. That could soon change. Wash. Post, (March 24, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/sex-trafficking-survivors-are-treated-as-criminals-in-virginia-that-could-soon-change/2021/03/24/b8224ad2-8cc5-11eb-a730-1b4ed9656258_story.html.

[9] Marsh et al., supra note 7, at 10.

[10] Id. at 16.

[11] Sheila Hayre, Decriminalize victims of human trafficking, Hartford Courant, (Jan 21, 2020), https://www.courant.com/opinion/op-ed/hc-op-hayre-human-trafficking-0121-20200121-3p4njud7tva53h6pqe2votkkwu-story.html.

[12] Marsh et al., supra note 7, at 31.

[13] Melissa Broudo & Sienna Baskin, Vacating Criminal Convictions For Trafficked Persons, SEXWORKERS PROJECT, 3 (2012), https://sexworkersproject.org/downloads/2012/20120422-memo-vacating-convictions.pdf

[14] National Survivor Network, Impact of Criminal Arrest and Detention on Survivors of Human Trafficking (2016), https://mvlslaw.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/NSN-Survey-on-Impact-of-Criminalization-2017-Update.pdf.

[15] Id.

[16] Hayre, supra note 11.

[17] OJPC, Who Can Apply For Safe Harbor Expungement? (2018), https://ohiojpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Safe-Harbor-for-clients.pdf.

[18] H.B. 425 Section 2953.38 132nd Gen. Assemb., (Ohio 2019).

[19] The Ohio Senate, 134th General Assembly, Fedor Testifies on Expungement Legislation for Human Trafficking Survivors (June 22, 2021), https://ohiosenate.gov/senators/fedor/news/fedor-testifies-on-expungement-legislation-for-human-trafficking-survivors.

[20] Id.

[21] Rebecca Vallas, Sharon Dietrich, & Beth Avery, A Criminal Record Shouldn’t Be a Life Sentence to Poverty, CAP (2021), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/criminal-record-shouldnt-life-sentence-poverty-2.

[22] Rights4girls, Racial & Gender Disparities in the Sex Trade (2019), https://rights4girls.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Racial-Disparties-FactSheet-_Jan-2021.pdf.

[23] Id.

[24] Cheryl N. Butler, The Racial Roots of Human Trafficking, 62 UCLA L. Rev. 1464, Abstract (2015).

[25] Id. at 1501.

[26] Id. at 1468.

[27] U.S. Dep’t. of State, Trafficking in Persons Report 9 (2013), https://2009-2017.state.gov/documents/organization/210737.pdf

[28] Id.

[29] Marsh et al., supra note 7, at 4.

[30] Pelto, supra note 1, at 507.