Missing White Woman Syndrome: How Gabby Petito Reminded Us that Women of Color’s Disappearances are Largely Ignored

By Alexis Franks

Associate Editor, Vol. 27

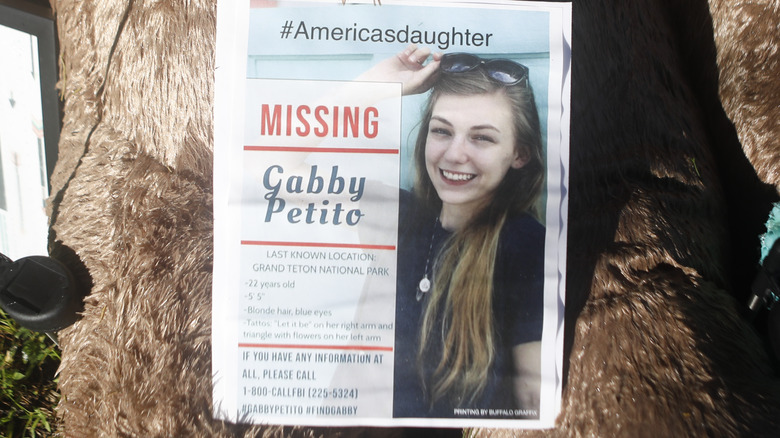

When Brian Laundrie pulled his white van into his family’s driveway on September 1st, 2021, friends and family all began asking the same question: where was Gabby? Brian and his fiancé, Gabby Petitio, had set out on a cross-country road trip one month before Brian’s unexpected return.[1] Their travels were documented on social media—colorful, aesthetic photos of the smiling couple filled Gabby’s Instagram feed.[2] Facing an onslaught of questions about Gabby’s whereabouts, Brian Laundrie opted for silence.[3] Within days, Gabby’s face was plastered on the front page of every major news outlet.[4]

At any given time, approximately 90,000 people are missing in the United States.[5] It stands to wonder what makes Gabby so special. The answer is simple—she is white. She is a missing “blue-eyed, blonde adventure-seeker,” and is, therefore, America’s favorite tragedy.[6]

The media attention garnered by Gabby’s disappearance stands in stark contrast to the media’s total disinterest in reporting disappearances that do not involve white women.[7] Gabby’s disappearance, and the media frenzy that followed, exemplified the media’s “round-the-clock coverage of [missing] young females who qualify as ‘damsels in distress’ by race and class.”[8] Meanwhile, vanished women of color are largely forgotten. This phenomenon, known as “Missing White Woman Syndrome,” was coined by Black journalist Gwen Ifill nearly two decades ago.[9]

Gabby Petito went missing in Wyoming.[10] A report from the University of Wyoming found that 710 Indigenous people went missing in Wyoming within the last decade.[11] America learned about none of these missing people. By September 19th, authorities found Gabby’s remains.[12] Over the course of their search, they uncovered the bodies of nine other missing persons, many of whom were people of color.[13] One of these women was Miya Marcano, a 19-year-old Black college student who went missing shortly after Gabby’s case made headlines—but America never heard about Miya.[14] Had law enforcement prioritized Miya’s case, the outcome likely would have been different.[15]

There are several reasons the media fails to report the disappearances of women of color. First, America is captivated by the story of the young, beautiful white woman who has disappeared.[16] According to Jean Murley, an English professor at Queensborough Community College, “it’s an aberration, and it becomes a container for things like the loss of innocence or the death of purity.”[17] This symbolism is not applied to women of color. Second, white women are typically depicted as victims, while women of color are characterized as risk takers who are somehow complicit in their disappearances.[18] Danielle Slakoff, an assistant professor at California State University, Sacramento, explained that “white victims tend to be portrayed as being in very safe environments, so it’s shocking that something like this could happen, whereas the Black and Latino victims are portrayed as being in unsafe environments, so basically normalizing victimization.”[19] Third, newsrooms continue to be disproportionately white, and reporters tend to push stories that hit close to home.[20] Fourth, a 2020 study published in the academic journal Journalism Practice, found that police are the driving force behind which cases get media attention, and police rarely push stories about women of color.[21] A New York journalist explained, “our policy is, if it doesn’t come from the police, we’re not gonna put it on.”[22] Because women of color who disappear are far more likely to be labeled “runaways,” law enforcement fails to allocate resources to these cases, and rarely reports these missing women to the media.[23] And this problem does not stop with police misidentification! Even when a woman of color’s disappearance is undeniably suspicious, police who utilize the media worry that people might think the woman is “just another runaway.”[24] Consequently, the stories are rarely published.

Lack of media coverage for women of color is not just a social injustice, it can also have devastating effects on the progress of investigations. When a crime flashes on every news outlet in the country, people are likely to call tip lines, keep their eyes peeled, and recall helpful information that may have been previously brushed off as unimportant. The media coverage of Gabby Petito led to a major break in the case.[25] After two Wyoming campers saw the headlines, they immediately recognized the infamous white van as the vehicle they had inadvertently recorded for a vacation vlog.[26] After they went to law enforcement with this information, Gabby’s body was found near the location of the spotted van.[27] Because media coverage can be a helpful tool in law enforcement’s kit, it is important that women of color receive just as much air time as white women.

So, what can be done to ensure missing women of color are not forgotten? First, state legislatures need to enact laws that allocate resources to the search and recovery of women of color.[28] The current system continues to fail these women because cases of white women are typically prioritized. If resources were allocated specifically for women of color, law enforcement would have no choice but to conduct adequate investigations. Second, legislation should prohibit law enforcement from labeling missing women of color as runaways without considering alternative explanations for their disappearances.[29] Perhaps law enforcement should be required to sufficiently investigate a missing person’s report and present clear and convincing evidence that the person is a runaway before placing the case on the backburner. Lastly, general police training on racial bias in relation to Missing White Woman Syndrome would also be helpful.

The media is flooded with stories about vanished white women, but coverage of the hundreds of disappearances of women of color is virtually nonexistent. Missing White Woman Syndrome unveils an ugly truth about America—people place more value in the lives of white women than women of color. Although law enforcement is partially responsible for this injustice, we must also accept our responsibility. As Gabby’s father, Joseph Petito, pleaded in a news conference, we must “help all the people that are missing. It’s on all of [us]… to do that, and if [we] don’t do that for other people that are missing, that’s a shame. It’s not just Gabby that deserves this.”[30] So yes, #JusticeforGabby. But let our call for justice for women of color be just as loud.

[1] Amir Vera, Brain Laundrie: Constant updates have left authorities and the public confused about Laundrie’s disappearance. Here’s what we know, CNN (Oct. 7, 2021) https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/06/us/brian-laundrie-timeline/index.html.

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Jada L. Moss, The Forgotten Victims of Missing White Woman Syndrome: An Examination of Legal Measures That Contribute to the Lack of Search and Recovery of Missing Black Girls and Women, 25 Wm. & Mary J. Race, Gender & Soc. Just. 737, 740 (2019).

[6] Katie Robertson, News Media Can’t Shake ‘Missing White Woman Syndrome,’ Critics Say, N.Y. Times (Sep. 22, 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/22/business/media/gabby-petito-missing-white-woman-syndrome.html

[7] Id.

[8] Moss, supra note 5 at 741.

[9] Robertson, supra note 6.

[10] Vera, supra note 1.

[11] Id.

[12] Srishti Bungle, Opinion: Put an end to ‘missing white woman syndrome’, Wash. Square News (Oct. 29, 2021) https://nyunews.com/opinion/2021/10/29/gabby-petito-missing-white-woman-syndrome/.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Id.

[16] Helen Rosner, The Long American History of “Missing White Woman Syndrome”, The New Yorker (Oct. 8, 2021), https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-long-american-history-of-missing-white-woman-syndrome

[17] Id.

[18] Robertson, supra note 6.

[19] Id.

[20] Id.

[21] Matt Pearce, Gabby Petito and one way to break media’s ‘missing white woman syndrome’, L.A. Times (Oct. 4, 2021, 5:00 AM), https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2021-10-04/gabby-petito-and-breaking-the-white-missing-women-syndrome.

[22] Id.

[23] Moss, supra note 5 at 752.

[24] Pearce, supra note 21.

[25] Rosner, supra note 16.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Moss, supra note 5 at 738.

[29] Id. at 761.

[30] Pearce, supra note 21.