Forever Barred: Examining Felony Disenfranchisement in Florida

By Shanene Frederick

Associate Editor, Volume 23

Executive Articles Editor, Volume 24

Desmond Meade was convicted on felony drug and firearm charges back in 2001.[1] Meade, who previously battled drug addiction and experienced homelessness, went on to earn a law degree from Florida International University College of Law.[2] However, his decades-old convictions continue to affect his life today in the form of disenfranchisement. In 2016, Meade could not vote for his wife during her bid for office in the Florida House of Representatives because Florida permanently bars those with felony convictions from voting after they complete their sentences.[3]

As the director of Floridians for Fair Democracy, Meade and his team of volunteers have petitioned for over two years in an effort to get a constitutional amendment proposal on Florida’s November 2018 state ballot. [4] Last month, Floridians for Fair Democracy announced that the campaign, Florida Second Chances, had surpassed 799,000 certified signatures, putting it above the required threshold to get on the ballot.[5] If passed, the amendment would restore voting rights to over 1.5 million Floridians, who have been subject to what are arguably the harshest felony disenfranchisement laws in the country. [6]

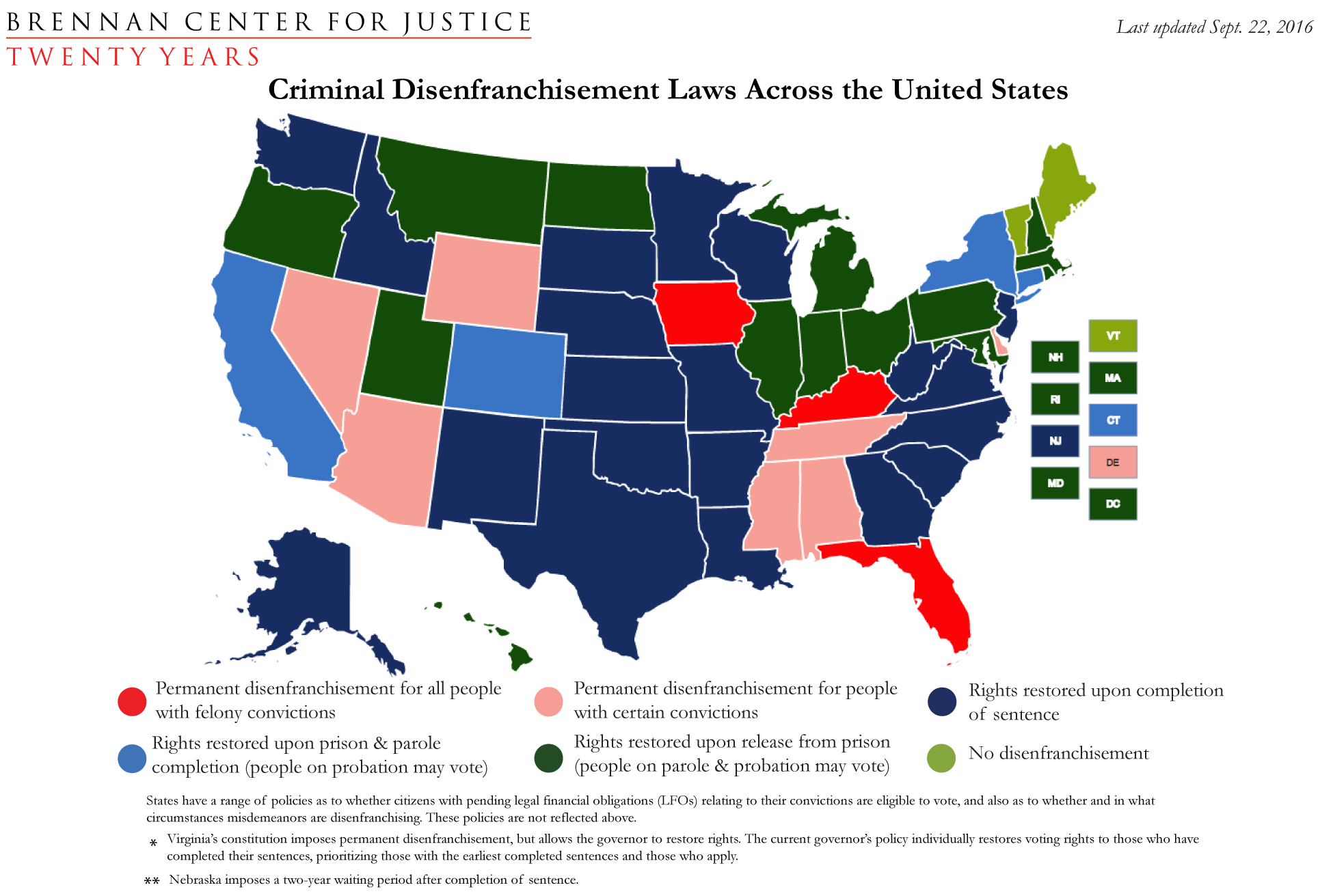

The states take various approaches to felony disenfranchisement. As of 2016, all states but Maine and Vermont bar those incarcerated from voting, thirty states restrict those on felony probation from voting, and thirty-four states restrict parolees from voting.[7] Florida is one of twelve states that strip away voting rights post-sentence and post-parole.[8] The effects of Florida’s disenfranchisement scheme are particularly startling: Florida holds 27 percent of the nation’s disenfranchised population, and the total 1.5 million post-sentence disenfranchised individuals make up 48 percent of those who are disenfranchised post-sentence nationally.[9] In 2016, 10.4 percent of Florida’s eligible voting age population was denied the right to vote.[10]

Nationally, one in 13 African Americans of voting age is disenfranchised, a rate four times greater than that of non-African-Americans.[11] Over 7.4 percent of the adult African-American population is disenfranchised compared to 1.8 percent of the non-African-Americans.[12] The number of disfranchised individuals in Florida is also disproportionately African-American: in 2016, more than 21 percent of Florida’s eligible black citizens were disfranchised.[13]

These racially disproportionate statistics did not happen by chance. Rather, they are the product of racism and discrimination against African-Americans going back centuries. Erin Kelley from the Brennan Center for Justice notes that after the end of the Civil War and passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, “disenfranchisement became a significant barrier to U.S. ballot boxes. First, lawmakers —especially in the South —implemented a slew of criminal laws designed to target black citizens. And nearly simultaneously, many states enacted broad disenfranchisement laws that revoked voting rights from anyone convicted of any felony.”[14] The result is the widespread, racially imbalanced felony disenfranchisement of today.

What makes the situation in Florida particularly harmful is the process disenfranchised persons are subjected to in order to regain voting rights. Currently, Floridians can only regain the ability to vote if they apply directly to the state’s Office of Executive Clemency.[15] The current restoration process, implemented by Governor Rick Scott in 2011, resulted in less than 2,000 applications granted in December 2015, while 20,000 applications remained pending.[16]

On February 1, 2018, Tallahassee federal district court judge, Mark Walker, found Florida’s voting restoration scheme unconstitutional, violating the rights of association and free expression guaranteed by the First Amendment.[17] Judge Walker noted that in order to regain their right to vote, those with felony convictions must “kowtow before a panel of high-level government officials over which Florida’s Governor has absolute veto authority. No standards guide the panel. Its members alone must be satisfied that these citizens deserve restoration.”[18] The right of states to disenfranchise those convicted of felonies has been settled by the Supreme Court as permissible under the Fourteenth Amendment.[19] However, the district court ruled that once Florida created a process for restoring voting rights, that process could not operate arbitrarily.[20]

While the suit continues, the people of Florida will get to express their opinions at the polls this November. If 60% of voters approve of restoring the right to vote[21] for those with felony convictions, more than a million Florida citizens, many of them African-American, will have their political voices heard once again.

[1] Steven Lemongello, Floridians will vote this fall on restoring voting rights to 1.5 million felons, Orlando Sentinel (Jan. 23, 2018), http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/politics/political-pulse/os-florida-felon-voting-rights-on-ballot-20180123-story.html.

[2] Id.; Chris Kromm, Campaign mounts for ‘second chances,’ restoring voting rights in Florida, Facing South (Mar. 24, 2017), https://www.facingsouth.org/2017/03/campaign-mounts-second-chances-restoring-voting-rights-florida.

[3] Lemongello, supra note 1.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] See Christopher Uggen, Ryan Larson, & Sarah Shannon, 6 Million Lost Votes: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016, The Sentencing Project (Oct. 6, 2016), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/6-million-lost-voters-state-level-estimates-felony-disenfranchisement-2016/#II.%20Disenfranchisement%20in%202016.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] Id.

[14] Erin Kelley, Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History, Brennan Center for Justice (May 19, 2017), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/publications/Disenfranchisement_History.pdf.

[15] Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Florida, Brennan Center for Justice (Feb. 12, 2018), https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-florida.

[16] Id.

[17] Hand v. Scott, No. 4:17cv128-MW/CAS, 2018 WL 658696, at *4 (N.D. Fla. Feb. 1, 2018).

[18] Id. at *1.

[19] See generally Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974).

[20] Hand, 2018 WL 658696, at *3.

[21] Fla. Const. art. XI, § 5.